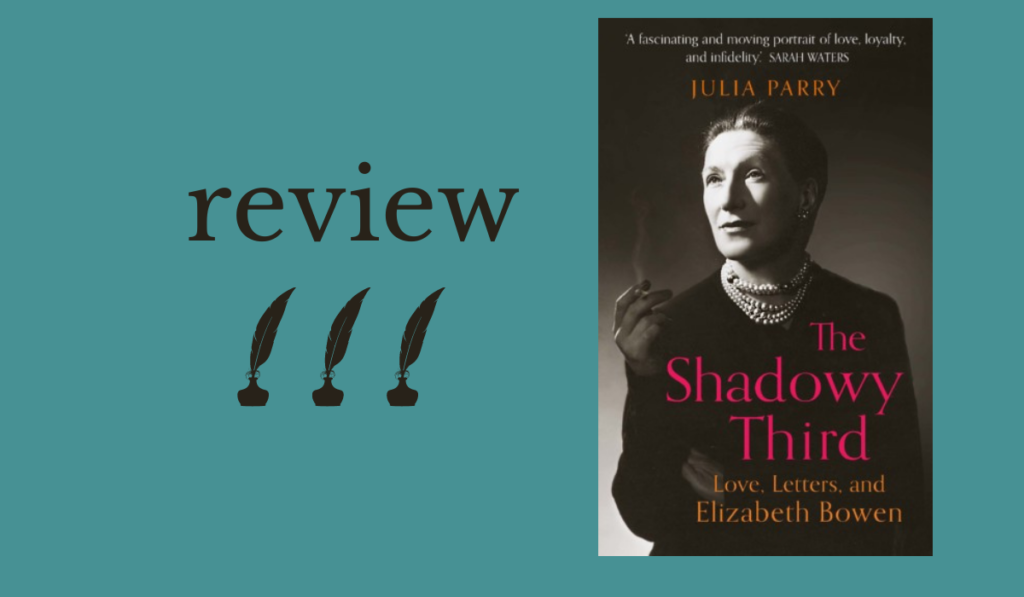

The Shadowy Third: Love, Letters, and Elizabeth Bowen|by Julia Parry|Duckworth Books|ISBN: 9780715653579|Hardback|£17.00

by NUALA O’CONNOR

In the first chapter of Julia Parry’s wonderful account of the affair between her grandfather Humphry House and Irish writer Elizabeth Bowen, she says that in the pair’s letters ‘their charged presences can be felt’. This holds true for the book Parry has written: she brings the players – Bowen, House, and Madeline, his shadowy wife – to vivacious, charged life, through a narrative that is part memoir, part creative non-fiction, part personal odyssey. Hilary Mantel says she writes about the past in a kind of mourning state; here, Parry resurrects the dead through their words to understand and celebrate them, and she does it with fair-minded probing.

A Bowen fan, Parry inherited both sides of the almost complete Bowen-Humphry correspondence, and these letters seemed to beg her to bring them to the light in some form.

Reading the letters, Parry recognised aspects of herself in Bowen – ‘spontaneous, wholehearted, occasionally overbearing’ – and admits to being bewitched by the writer. House, an intellect, teacher and writer, and a man Parry never met, is examined unflinchingly – he had a propensity for self-interest that, even in the context of the times, reads as vast selfishness, and the reader cannot help but be on the side of the put-upon and, often discarded, Madeline.

House’s affair with the married Bowen grew and deepened at the same time he was ready to marry Madeline. This scenario occurred again for Bowen when her lover Charles Ritchie – the love of her life – married his cousin Sylvia while still emotionally and intellectually entangled with the writer.

Bowen’s husband Alan Cameron tolerated her infidelities, and their marriage was solid, though not always pain-free.

For Madeline and Sylvia, things could never be so easy – their hurts were rarely considered. They were perceived as marriage material, with a certain supportive, domestic role to play, though Madeline later co-edited Dickens’s letters with House. Elizabeth – already safely married in her twenties – was older, and she represented everything other than ‘wife’ to the men who had affairs with her; she was firmly Elizabeth Bowen: well-known writer, lover, intelligent companion, exacting friend, and stylish hostess.

When in Ireland, House, Ritchie, and others, lived vicariously through Bowen as Big House dwellers, and she generously shared Bowen’s Court, her Irish home, with them. There was often more of a meeting of minds than bodies between Bowen and her lovers and, for her part, Bowen described Madeline House as mediocre, depressing, and ‘always pop-eyed with anxiety’. Parry writes: ‘Both Humphry and Elizabeth tried to exile Madeline to the marginalia of their narrative.’ But when Madeline is allowed to step onto the page, the reader finds her vivacious, committed, pragmatic, and bright, a much more humane human than either her husband or Bowen.

House was a man struggling – like James Joyce, he seemed to need to create flurry in order to feel alive. He achieved this by moving location, switching jobs, drinking, and having extra-marital love interests. House, unlike Joyce, was not buoyed up by family life, but drowned by it, and he retained many freedoms. He often kept separate, city quarters to the family home and, in 1936, he left England to work in India at Presidency College in Calcutta. Going there meant leaving Elizabeth but, more crucially, he left a pregnant Madeleine, and their new baby; she returned to live with her parents during her husband’s absence which would last two years.

Loving someone is not easy and sometimes being loved by them is hard too.

This narrative, and particularly the letters, are alight with affection and admiration, but also tough love and a consistent reckoning: House and Bowen unpick each other’s personalities and demand the righting of perceived wrongs; House and Madeline play out their frustrations with one another in their written pages too. The frank openness the couples employ is refreshing – there was little possibility of misunderstanding because they did not let each other away with anything.

What is harder to digest is House’s lack of presence with his wife and children, and Bowen’s attitude towards the innocent Madeline. Bowen makes no secret of her disdain for Madeline to Humphry House or other friends, while also maintaining a society-demanded politeness: she and Madeline had several shared meals and mutual visits which read uncomfortably. Bowen and House had a certain duality of nature in common – they wanted to have things both ways and were upset when life ruffled their plans. The impression is always that Bowen’s marriage to Cameron is beyond criticism, a no-go zone for examination, her situation being understandable and necessary. In contrast, she sees the unions of her lovers as less important and, often, as affronts.

After we die, we are fictionalised – stories start to weave around us, filtered ones, that are loaded with others’ opinions and memories. In The Shadowy Third, Julia Parry does an excellent, empathic job of managing these stories; she marries testimony with hearsay, motive with circumstance, and place with atmosphere, and fashions all of it into a compelling, seductive narrative. Humphry House and Elizabeth Bowen are fascinating, large characters in this book. Their work is the most important thing, but Bowen also tells House she longs for a child; House has a family but doesn’t seem to want to spend time with them, preferring to pursue his career and concerns beyond his marriage. Madeline House – Labour activist, editor, good mother to her three children, and loyal, patient wife – comes off the best in this engaging trio. Perceptive, adventurous, large-hearted, and dynamic, Madeline has more endurance and balance than the others, it seems. The reader can only lament that her husband could not step up to meet and support her, and ensure she had the rounded home and work life she really deserved.

Nuala O’Connor‘s latest novel, Nora (New Island Books), about the life of Nora Barnacle, launches on 9th April, 7pm GMT online in association with MOLI. Interview with Katherine McSharry of the National Library of Ireland. Register here.

There will be a Galway launch on 23rd April, 5.30pm GMT online in Galway in association with the Cúirt Festival. Interview with Elaine Feeney. Book here.