Mary Watson moved to Ireland from South Africa and literally wrote herself into this country

There was a drunk man, one night in town, who wouldn’t leave me alone. I’m not the first with this story. He followed us, fixating on me, as I walked with a friend. We were uncomfortable, a little afraid, and about to walk down a dark, quiet road. The encounter made me strangely paralysed. I’m usually well able to speak out, but I couldn’t say anything to this man. He was wild-eyed and swaying on his feet, which made him both less and more of a threat. As I stood there, utterly voiceless while he invaded my space, my friend yelled at him to leave us alone.

What was it that had me so stupidly afraid of someone I knew probably couldn’t hurt me? We recounted this incident recently, embellishing and adding in a few laughs. And at the end of the retelling, I admitted what I had found most terrifying about the whole thing: I was afraid of racial slurs. I was afraid that he would tell me to go ‘home’, that he would make a comment about my skin colour, that he would resort to the unpleasant names in currency for women who look like me.

I don’t think this had occurred to my friend until I admitted it recently. Much of the time she likely forgets that I’ve spent most of my life living somewhere else; because we have the same interests, books, movies, having a laugh, fashion, our local community, being mothers and all that entails. Apart from when I might recount a story from my life before, or when I refuse to go for a walk in the rain, I’m not exactly different. But I am a little different.

There are other stories inside me that influenced how I responded to this man. Stories from elsewhere, of growing up in apartheid South Africa with all its rules that dictated where I could live, what beach I was allowed to go to, where I could sit on a train or even on a bench at the station. Of the persistent centering of whiteness in everyday life, through law and through the media.

These stories have been rekindled by the recent animosity stoked in the world of Trump and Brexit, where there is increased license to hate. I’ve not experienced much animosity here in Ireland—invisibility, yes, but not outright hostility. But I know women, Muslim and black, who have been verbally abused because of what they look like. So, drunken pestering, disturbing in itself, gains an added layer of antipathy.

And just as people have their stories that influence how they may respond in a situation, books have hidden layers of stories too. The foundation of both The Wren Hunt and The Wickerlight was my move to Ireland from South Africa ten years ago. I came for the adventure, for the story, but it was harder than I’d expected. There were lots of reasons: my mother’s terminal cancer eighteen months into our move, the early stages of motherhood, the relentless wet weather, the recession and the loss of my academic career. I was homesick and unhappy for a long time. Eventually, fed up, I decided I would fix it through writing: I would write a story I could only write here. I would literally write myself into this country, sending out words like roots that would reach down until I was firmly planted here.

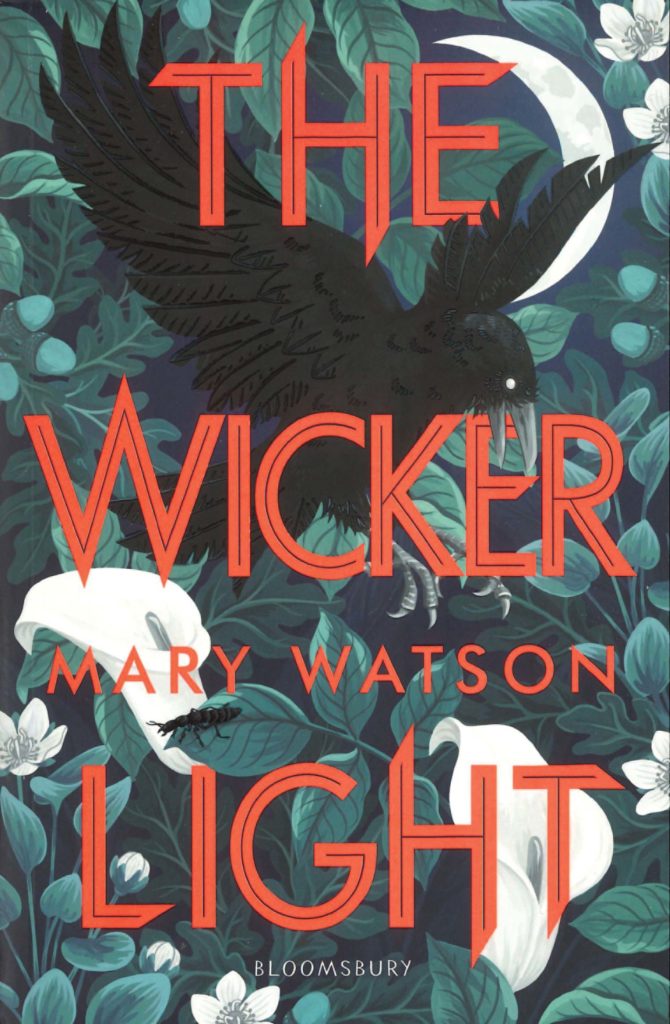

The Wren Hunt is fundamentally about belonging. Wren is an outsider, uncertain of where she fits in. Although it takes a different form, the story is a view of a deeply personal struggle. The second book is more outward looking. While it may be a story about secret communities and feuding magical factions, The Wickerlight is also about immigration. At the core of the novel is a second generation immigrant girl who, longing for acceptance, dies trying to access the secrets of her community. In both books, a kind of metamorphosis, changing from one thing to another, is key.

There’s an informal tradition of diasporic writers grappling with their displacement or isolation or assimilation through writing. And The Wren Hunt is my attempt at this. I wanted to avoid the obvious, and contemporary fantasy, that draws on mythology, felt like the right form for telling this story. I’ve always loved Irish mythology, but it wasn’t enough to simply write a story that extends existing myths. To find a place for myself, I needed to make my own myths, complementary to and inspired by the stories that are already here. But also inspired by the stories inside me, the ones that reach down to the child at the beach staring at the sign that says ‘Whites Only’, to the woman who couldn’t speak up to a drunk man. There are many others, too: stories of friendship, of betrayal, of girl meeting boy, of familial bonds. And packed together, they make up the invisible foundations, the hidden stories, of these books.

Mary Watson’s latest novel is The Wickerlight (Bloomsbury).

Article first published in Books Ireland Jul/Aug 2019