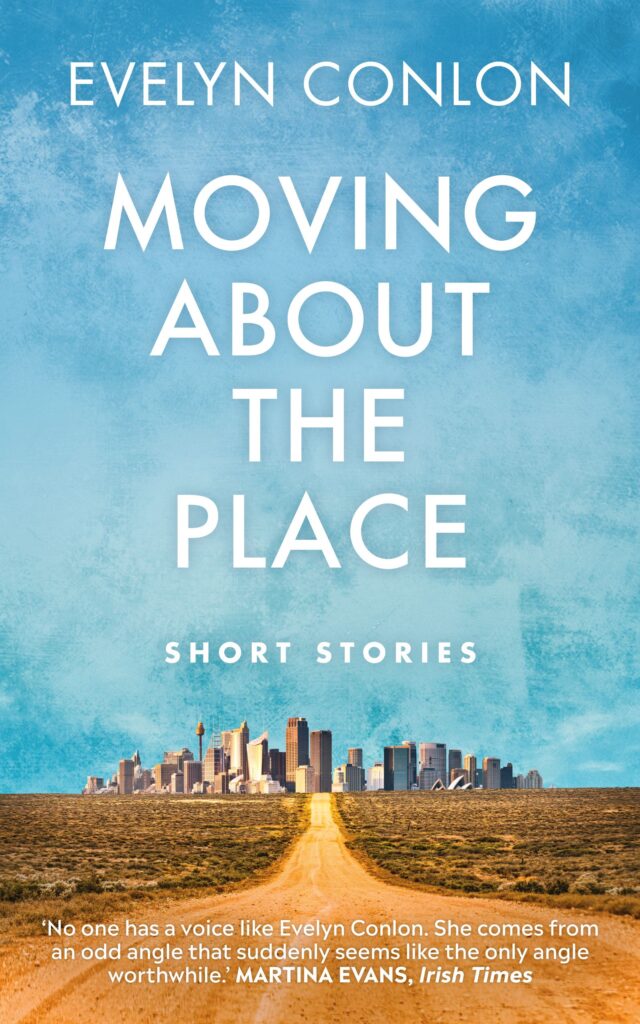

Moving About the Place|Evelyn Conlon|Blackstaff Press|ISBN: 9781780733104|£12.99

An extract from Moving About the Place, by Evelyn Conlon

How Things Are With Hannah These Days—an extract from the novella

Hannah Grogan went out to Australia on the assisted passage in the early nineteen seventies with her spanking new husband.

Anyone who had been there on the day they left remembered it well; they had all piled out to the airport to wave them goodbye. There had already been weeks of mentioning, looking towards the day as it progressed along the calendar like a tide coming in. Marcus, one young cousin, was, as usual, even more embarrassed than his sister Tara. He had tried feigning a sick stomach: ‘Awful pain there,’ he said and he touched a spot that he knew always put a worried look on their mother’s face. But recently the doctor had told her that there was not one single thing wrong with him, so he was forced into the back of the car, where he promptly kicked Tara, but she didn’t bother kicking back because she was thinking of the new spiral building at Dublin airport. She’d seen the picture of it on the back of a shiny magazine and wondered if they would get a look. She was also trying to remember where that could have been, because certainly her mother didn’t buy shiny magazines.

There was great excitement for an hour or so as different family members arrived. Then someone was heard asking ‘Has Millie come yet?’

‘No, of course not,’ came a reply. ‘I’m glad it’s not her that’s going – she’ll miss her own funeral that one.’

The cousins switched off at this, realising that the same old things they’d heard every Christmas were going to be repeated here today. But then Hannah and the new husband arrived – they never thought of him as having a name, no need really – and the atmosphere changed. The air seemed to get full: there was a lot of overlapping talk, sentences piled on top of each other like sandwiches.

‘Oh, I’ll be lonely without her,’ Hannah’s mother said.

‘It’s only for a few years,’ an aunt hurriedly replied, doing her best to minimise the significance of the event, but secretly glad it wasn’t one of hers that was going.

‘It’s very far though, very far, worse than America, even the west coast.’

No one replied to that.

Marcus and Tara liked this new talk of faraway places and were prepared to allow that their relatives might know something of interest. They didn’t even mind the family caravan wiggling towards departures; they quite liked the whole thing really, until the crying started.

At first it was just sniffles, punctuated by the occasional sob, then it reached a crescendo of full-blown weeping, still low enough for passers-by to politely ignore, but then Aunt Mags let out a wail. It came suddenly, apparently not attached to any previous sound. At that stage of their lives, they were not aware of the fact that she was known as a crier. At funerals people tried to rush her away before she got started, and if they couldn’t manage that they put as much distance as possible between themselves and her. The sound stopped people in their tracks; they couldn’t avoid snapping their necks in its direction. Tara blushed hot scarlet and then ran to join Marcus, who had, with remarkable speed, got himself well positioned behind a pillar so that no one would know who he was with.

That was the last they’d seen of Hannah, years ago. They had missed her actual departure, being so well hidden behind the pillar, and no matter how their names were shouted out to ‘come say goodbye to your cousin’, they ignored them, knowing that something bad would probably happen to them for this sullying of the moment of leave-taking.

Tara had heard the odd scrap about Hannah since then but wasn’t remotely interested; she had growing up to do. But now here was this strange letter, wielding years of Hannah’s life in front of her, as if she’d never gone through those airport gates. Being honest with herself, Tara thought she had enough relatives and didn’t need any more, whether newly discovered ones, adopted, black sheep – that sort of thing – or ones resurrected. She had become a satisfied enough young woman with no desire whatsoever to do leave-takings at Dublin airport. But manners demand that you don’t drop a letter half read so she stayed with it right up to Hannah’s peculiar request that she come visit her. ‘My mother and yours said that you just might.’

Hannah and the new husband had first flown to London, where they stayed the night in a hotel. Simon was his name. They had gone for a drink in the bar and met a Welshman who would be going on their ship. He had recently left the priesthood, he told them. He had a Teddy-boy haircut, which had been all the rage when he went into the seminary. He thought, all things considered, that it would be best to start again far away from Carmarthen. Hannah had found something shockingly sad about him, epitomised by the sartorial years that he had missed.

She thought she would avoid him on the boat if she could, and immediately felt mean. In the morning, while she was getting ready and checking the bags once again, just to be sure, Simon had gone shopping, got delayed and almost missed the bus to Southampton. God how she remembered it. The panic had made her realise what she had done, and where she was going, and how far away it was. But she couldn’t turn back now. She had tried to look at the English countryside from the bus window – it was, after all, different to her own, and in other circumstances could have been the makings of a holiday. Yet she found it made no impression on her at all. It couldn’t get in behind her galloping thoughts.

After some hours they arrived and stepped off the bus, down where the port smelled of port. In the hall leading to the ship, passengers began to queue, some in a more organised, hopeful way than others: English, Scots, Swedes, Danes and a miscellaneous few Irish, none of whom Hannah had yet met. They queued all day, eventually swapping with each other to allow an occasional rest on the seats, and when the visas, the health cards, the passports were checked they were given a cabin number, a number for meals – first, second, third sitting – welcomed aboard, and swallowed by the mouth of the boat. It didn’t take long once they reached the top of the queue. They made their ways, over the gangplank, to cabins that were deep down in the noise of the engines.

When their wardrobe was unpacked, hung up, and their toiletries placed on shelves, Hannah went wandering. She found the swimming pool on deck, the hairdresser’s, a doctor’s surgery, shops, a beautician’s corner, a musty library and several bars. Only two hours had passed. She went back to the cabin. It was lucky that she and Simon did not know each other long. There was less danger of getting bored because of that, she thought. They had the lifesaving gear put on and laughed over, even photographed, before any safety announcement was made. One more hour.

At the fourth hour their dinner sitting was called. Neither Hannah nor Simon had ever been on any kind of ship before, never mind a Greek liner, so they stepped their way cautiously to the dining room. They made several mistakes before finding it, but were finally guided by the sounds of cutlery and the smell of apple juice. What first struck Hannah was the size of the waiters: small, almost tiny, men, all wearing black trousers and red cummerbunds. She had never before thought of height difference as a marker of nationality, and was aware of the depth of her awful ignorance; not ignorance as in brutishness, ignorance as in simply not knowing, or not having thought of certain facts. But now she would learn. She was a little disturbed that it was the waiters who first caught her eye. Shouldn’t marriage have annulled those noticings? Their designated waiter led them to a table to meet their fellow diners, people with whom they would spend every mealtime for the next four weeks.

Hannah included a photograph of this dinner table in her letter to Tara. It seemed an odd thing to do, a confusing clue to what had become her life.

Hannah had, for years, thought the journey of little interest to anyone except to herself, and then only in flashes, like when a particular kind of bell rang in a supermarket – the type that reminded her, with a jolt, of the ship’s call to meals – or safety drill announcements. But in this letter, she wrote the details of the voyage matter-of-factly, as if everyone did spend a month at sea sometime during their lives. When she had posted the letter with the photograph in it she was suddenly embarrassed, as one would be when a private thought slips out to become nonsense once spoken. Too late now.

Moving About the Place brings together some of the best of Conlon’s recent work, along with brand-new stories, including a novella, to show how borders, movement and history change and transform people’s lives.