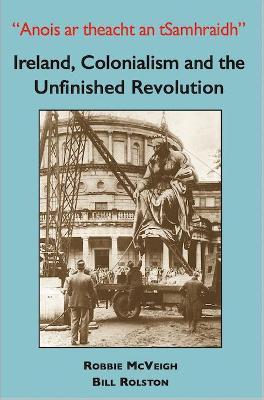

Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution|Robbie McVeigh & Bill Rolston|Connolly Books|ISBN:9781914318009|€25

“…part history and analysis, a blast against revisionists and apologists for British rule, and an outline of a possible future.”

—TONY CANAVAN on Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution

by Tony Canavan

Was Ireland a colony of Britain? Is Northern Ireland a colony of Britain? These are questions that have divided both historians and politicians over the decades.

In a purely legalistic sense Ireland was not a colony. Between the Norman Invasion and the reign of Henry VIII, Ireland was a papal lordship.

Adrian IV (the only English pope) issued a Bull, Laudabiliter, which granted authority over Ireland to any English king who would reform the Church there. Henry II used this Bull to legitimise his invasion in 1171 and English kings continued to call themselves lords of Ireland.

Contention

When Henry VIII rejected papal authority he also rejected his authority to rule Ireland. He solved this problem by declaring himself King of Ireland, creating a ‘sister’ kingdom to England.

If Ireland was not a colony, undoubtedly there were British colonies in Ireland, most notably the 17th century Plantation of Ulster.

Nevertheless, Ireland remained a nominally separate kingdom until the 1801 Act of Union absorbed it into the United Kingdom. Thus, in theory, the inhabitants of Ireland were British, indistinguishable from the inhabitants of Britain.

The contention of this book is that Ireland was an imperial colony of Britain and that Northern Ireland is de facto a colony to this day.

Setting aside the constitutional niceties, I think that any impartial observer would have to agree that Ireland was a colony.

Tackling issues head-on

It may be difficult to pin down an exact time when this happened, but certainly the post-Williamite settlement saw Ireland completely subdued and rendered subordinate to and dependent on Britain.

Even after the Act of Union, Ireland was governed differently from the rest of the United Kingdom and Irish people did not enjoy the same rights as the people of Britain.

Whenever the Irish attempted to assert their self-determination, whether peacefully or by force, they were suppressed by the British until a (partially) successful War of Independence saw the establishment of an Irish state, with six northern counties remaining in the UK.

McVeigh and Rolston tackle these issues head on and unequivocally nail their colours to the mast. Their book is part history and analysis, a blast against revisionists and apologists for British rule, and an outline of a possible future. This is a challenge for any book but the authors manage to address all the issues comprehensively.

Conceptual tools

They base their analysis on what they call the conceptual tools of gender, race, class, sectarianism and mestizaje. They use these tools to dice and slice the various phases of Ireland’s development from a colonial country to a post-colonial one.

They treat Northern Ireland separately, recognising the reality of facts on the ground, to coin a phrase. However the authors do not have a narrowly focused view but place Ireland’s past and future in an international context, drawing comparisons and contrasts with imperial set-ups across the globe.

In doing so, they engage with issues of class and identity. In relation to the latter, they raise some thought provoking issues about the ‘whiteness’ or otherwise of the Irish. This emerges as central to their analysis of modern Irish society.

They point out that the Irish have not always been regarded as white, and for centuries were seen as ‘other’ similar to people of African descent. They say that this has changed to the extent that the Irish are accepted as ‘white’ and the Republic seen as a ‘white dominion’.

However, they warn of the dangers of aligning Irishness with ‘whiteness’, not only highlighting the many prominent Irish people of colour – from Phil Lynott to Leo Varadkar – but also the dangers in cutting ourselves off from our own colonial experience.

Detailed and considered

This is a detailed and thoughtful book. It does not pretend to be impartial but argues a particular case, which becomes clear in the final section on Ireland’s future. One may not agree with all, or any, of what the authors say but they raise issues that should be recognised and addressed.

Viewing Northern Ireland through the colonial prism, for example, casts the Troubles and Peace Process in a different light.

The authors say it is not an academic text but it has copious footnotes and quotations from commentators and source documents, and I think that not many general readers will plough their way through it. At times it can be didactic and repetitive, which will not appeal to all.

I did enjoy reading it and found it a trove of informative quotations from the various declarations, parliamentary acts, and other documents that have a bearing on modern Irish history. It will be interesting to see what impact it has.