Irish Lives in America|ed. Liz Evers & Niav Gallagher|Royal Irish Academy|ISBN: 9781911479802|€19.95

Political figures and architects, artists and entertainers, soldiers and scientists, slaveholders and abolitionists, Irish Lives in America spans more than three centuries, a reminder of the long ties between the two countries.

—Liz Evers and Niav Gallagher on the people who live and breathe in the pages of their new book.

‘No Irish need apply.’ Oftentimes the enduring image of Irish emigration to the US is the one that popular culture has given us: young men and women forced from their homeland by poverty and oppression, coming to America to thrive against overwhelming odds. And, in some cases, this is true.

More often than not, however, the truth is considerably more complex and, as a result, far more interesting.

While searching the Dictionary of Irish Biography for fifty lives to include in our new collection, Irish Lives in America, we did indeed find examples of individuals who arrived with little more than the clothes on their back, who then went on to prosper.

Belinda Mulrooney

Belinda Mulrooney (1872–1967) was one such example – the daughter of a coalminer, she amassed a fortune in the goldmines of the Klondike which she then used to build a turreted mansion in Yakima, Washington.

Unfortunately, her bid for social respectability was undone by her unladylike proclivities for smoking, gambling, drinking whiskey and putting her feet up on the table; she ended her days cleaning steel welders in a Seattle shipyard.

But more common were those who escaped poverty in Ireland, only to remain in poverty in the US or, occasionally, those who were already wealthy and connected when they emigrated.

Annie Moore

For the most part, the stories of the poor remain largely untold, a notable exception being Annie Moore (1874–1924). She was the first immigrant to land on Ellis Island and she became a symbol, not only of Irish emigration to America, but of all who landed there.

Her story was one of hope, an example of the opportunities that awaited emigrants.

Unfortunately, it was also untrue – Annie’s story had been confused with another emigrant of the same name who moved to Texas and prospered. The real Annie Moore stayed in her Lower East Side neighbourhood in New York, living a life of hardship: six of her eleven children died of poverty and neglect, and Annie herself died at the age of fifty.

We wanted the biographies we chose to reflect the rich diversity of the emigrant experience, to illustrate that, far from being a homogenous group, the Irish leaving Ireland for the US werefrom a variety of backgrounds, regions and religions.

Reasons for leaving

Their reasons for leaving varied widely too: in the middle of the seventeenth century, they were mostly Catholic indentured servants fleeing the plantations of Ulster and lives of poverty, or prisoners-of-war sentenced to transportation by Oliver Cromwell’s regime.

By contrast those leaving Ireland throughout the eighteenth century were mainly Presbyterian planters seeking to escape religious and economic persecution brought about by the penal laws.

At the end of the century, they were joined by more than 2,000 young radicals from varying backgrounds who were forced to leave Ireland in the aftermath of the failed rebellion of 1798.

But all these groups were surpassed by the vast numbers who emigrated from famine-ravaged Ireland during the middle of the nineteenth century, a wave that lasted well into the twentieth.

Spanning three centuries

For more than three hundred years these different groups contributed significantly to their new home and not always positively: for every ‘Mother Jones‘ (1837–1940) and Joseph Patrick McDonnell (1846–1906) who sought to improve the circumstances of workers and the poor, there was a Pierce Butler (1744–1822) slave-owner and author of ‘the fugitive slave clause’ in the US constitution.

While Mary Jemison (c. 1743–1833), who was adopted into the Seneca tribe, provided one of the few authentic accounts of how colonial expansion affected Native American people, it is John Mulvany’s (c. 1844–1906) painting, ‘Custer’s Last Rally’ that has captured how generations viewed the colonisation of the American west – reimagining a humiliating defeat of the US army as a victory of grit and spirit.

Spanning more than three centuries of American history, Irish Lives in America illustrates how significant Irish influence on all aspects of American life has been – cultural, political, scientific and more.

Fifty biographies

Our earliest biography is that of James Logan (1674–1761), chief adviser to William Penn, public servant and scientist who was a founding trustee of the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania). His library is considered the finest collection assembled in pre-independence America.

And our most recent is that of Hollywood actress Maureen O’Hara (1920–2015) whose biography is one of two that were written specially for this volume.

She was known for her roles in big budget swashbucklers and John Ford pictures, and she was also one of the first people to be recognised as Irish, and not ‘English’ in her American citizenship paperwork.

In between are political figures and architects, artists and entertainers, soldiers and scientists, slaveholders and abolitionists. There are those who spent their lives fighting for the rights of workers; and there are industry titans who capitalised on the labour of others to become the country’s first millionaires.

Alongside familiar names such as the pirate Anne Bonney (c.1700–p.1721), inventor of the submarine John Philip Holland (1841–1914), film director Rex Ingram (1893–1950) and White House architect James Hoban (c. 1762–1831), we have included the less well-known, but no less important:

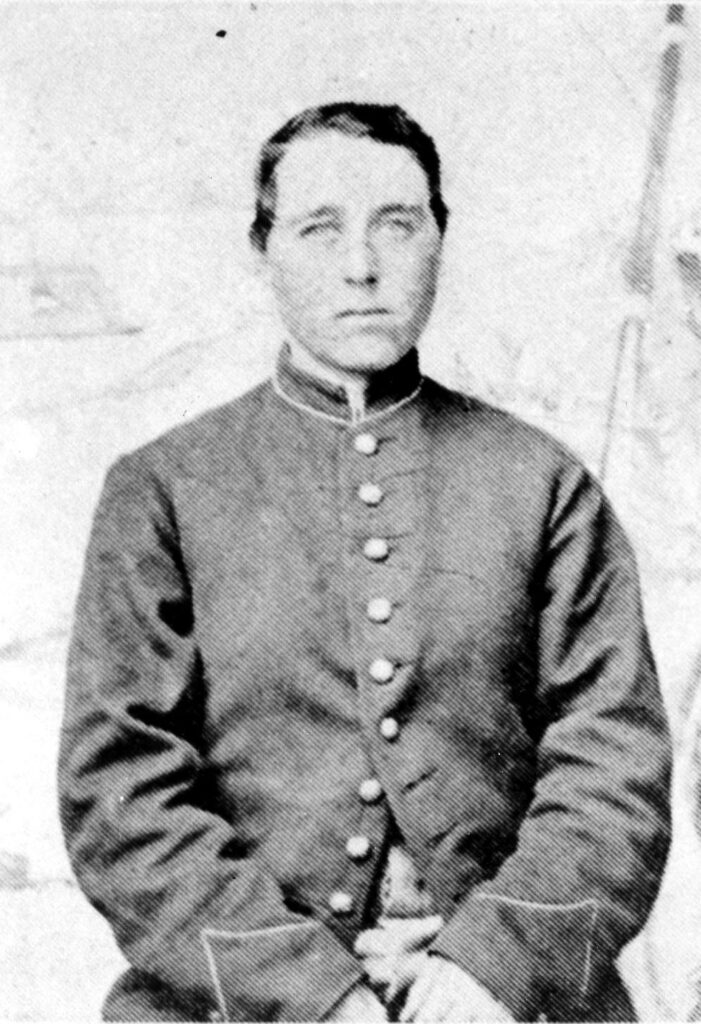

Gertrude Brice Kelly (1862–1934), one of New York City’s first female surgeons; Albert Cashier (1835–1915), another newly written entry, who was born Jennie Hodgers but lived all his life as a man, serving with distinction on the union side in the civil war; ‘Kay’ McNulty (1921–2006), who was a pioneering second world war computer programmer and Thomas ‘Broken Hand’ Fitzpatrick (1794–1854), a nineteenth-century mountain man who served as guide to westward-bound colonisers and was the first US agent to the tribes of the central plains.

A new and confident identity

The fifty biographies contained in our book represent the thousands of Irish who emigrated to America but whose stories remain untold outside of their immediate families.

Their descendants, 34.7 million at the last census in 2010, can be found in cities and states throughout the US, and in all walks of life, but how they view their ‘Irishness’ is changing.

A recent study by the UCD Clinton Institute, entitled Next Generation of Irish America, outlines how Irishness is no longer an overriding identity for young Irish Americans but, rather, is part of a multifaceted sense of who they are.

Irish Lives in America is a reminder of the long ties between two countries and the contribution that the Irish have made to their adopted homeland, but also of the solid base from which contemporary Irish Americans are free to forge a new and confident identity in the twenty-first century.

Liz Evers is a writer and editor who has worked in the publishing industry in the UK and Ireland for many years and is the author of several popular reference books on diverse subjects, from Shakespeare to horology. She is a graduate of University College Dublin (BA English) and Dublin City University (MA Film). She joined the Dictionary of Irish Biography as researcher and project copy editor in 2018.

Niav Gallagher is a medieval historian, specialising in the links between religion and politics in thirteenth- to fifteenth-century Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Among other roles, she has worked as a lecturer and as a researcher for genealogical and historical research company Eneclann, on several collaborative projects, including the National Archives Millennium Project and the Irish Battlefields Project. Niav is a graduate of University College Dublin (M.Litt.) and Trinity College Dublin (Ph.D.). She joined the Dictionary of Irish Biography as a researcher in 2018.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography is Ireland’s national biographical dictionary. Devised, researched, written and edited under the auspices of the Royal Irish Academy, its online edition covers nearly 11,000 lives. In spring 2021 the DIB made its full online respository free to access at www.dib.