Cathal Póirtéir with his latest choice of reading as Gaeilge

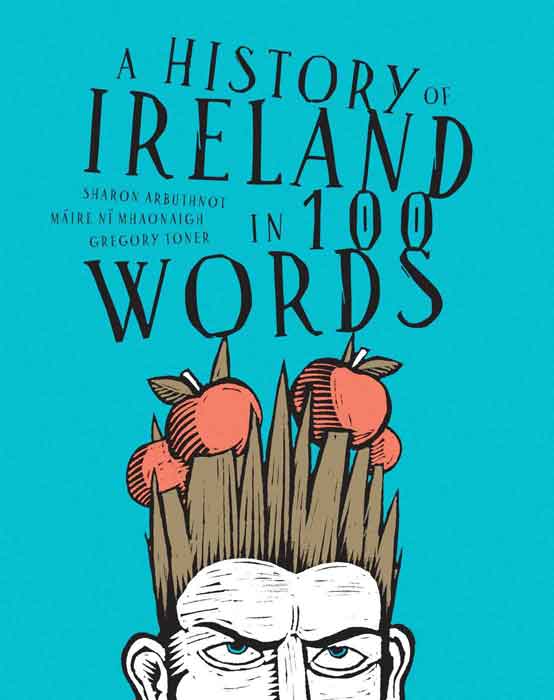

A History of Ireland in 100 Words

Sharon Arbuthnot, Máire Ní Mhaonaigh and Gregory Toner | Royal Irish Academy | €19.99 hb |288pp | 9781911479185

review by Cathal Póirtéir

This is a book for word lovers, particularly those with an affinity for the Irish language and its literature. Three scholars have combined their learning to give readers short, accessible and fascinating accounts of 100 words drawn from Irish-language literature, the most extensive vernacular literature in early medieval Europe. The introduction of the Latin alphabet to Ireland, with the advent of Christianity in the fifth century, saw manuscripts being written by monks in Latin and in Irish, and this grew to include detailed law and medical texts, religious writings, annals of important historical events, and a huge body of tales and poems about kings, warriors and women, ancient heroes and historic battles, love stories and tragedies, encounters with magical places and mythical beasts.

The introduction to this attractively presented book explains what that treasure trove of learning contains: ‘Through this enormous literary outpouring, these church men and scholars give us an insight into the beliefs, habits and daily lives of the Irish—how they ate, drank, dressed, loved and lied’. The editors use that resource as a way to explore the history of Gaelic Ireland, taking individual words, placing them in their literary and linguistic context, examining what they meant when they were first written down and how some of them survived into modern Irish with meanings that may have developed over the course of a thousand years or so.

The Irish language remained the main language in Ireland well into the nineteenth century, and all through that period scribes were at work recording traditional learning and literature. The development of the written Irish language over a millennium and a half means that a speaker of the modern language needs expert guidance to make sense of older writings and the editors and their expertise are at hand here to help us understand and enjoy that rich cultural legacy.

The impressive scholarship is delivered with a very light touch and a sense of humour, while still managing to deliver information that enlightens and entertains. The tantalisingly short contributions, two short pages to each word, leave you wanting more, and that is part of the motivation for this project. Readers are encouraged to go on to consult the magnificent Royal Irish Academy’s Dictionary of the Irish Language, now available online at www.dil.ie.

This book is a themed cultural dictionary you can dip into for two minutes or twenty, depending on your ability to drag yourself away from it. The different chapter headings give a good idea of what you can expect: ‘Writing and Literature’; ‘Technology and Science’; ‘Food and Feasting’; ‘The Body’; ‘Other Worlds’; ‘War and Politics’; ‘A Sense of Place’; ‘Coming and Going’; ‘Health and Happiness’; ‘Trade and Status’; ‘Entertainment and Sport’; and ‘The Last Word’. It is full of fascinating explanations of words, unexpected cultural and linguistic associations and endless delights. As well as the wonders of the words themselves, the book is a constant reminder of the tales and literary texts from which they are drawn. There is a guide to further reading, which includes many English-language translations of original tales, as well as a lengthy list of the manuscript, primary and secondary sources cited—a handy resource in itself.

There is so much to enjoy in this book and you won’t go many pages without being pleasantly surprised by discovering something new. It had never occurred to me that isteach and istigh, going inside and being inside, derived from teach and tigh, words for ‘a house’, and I found that many of the explanations included were clear when explained, but often not before. I’m sure our learned Uachtarán is aware of the origin of his surname, but most of us will not have considered that the family of Ua hUiginn (Higgins) derives from vikingr, the Old Norse word for ‘Viking’ itself. In a discussion of the word fliuch (‘wet’), we discover that in Munster Irish ag cur foirc agus sceana (literally, ‘raining forks and knives’) is a rough equivalent of ‘raining cats and dogs’. We learn that the French, because of the Anglo-Norman presence here, were seen as being the source of the cearc fhrancach (‘turkey’), cnó francach (‘walnut’) and luch fhrancach (‘rat’), although the word in these cases seems to have the meaning of big rather than French; and in another entry we are told, somewhat surprisingly, that the magical leipreachán comes from the Luperci, a group associated with the Roman festival of Lupercalia. We meet other mythical creatures throughout the book, including the fairies and the banshee. Not surprisingly, Fionn and the Fianna and their exploits are often referred to in words associated with them. Other figures from less well-known tales appear in descriptions of incidents or behaviour that throw light on wild and wonderful beliefs, imaginings and cultural traditions.

The volume has a lovely feel of quality to it and the many illustrations by Joe McLaren complement the vivid and humorous explanations supplied by the editors. If you enjoy etymology, eclectic cultural history or the Irish language and its lore, literature and mythology, this is a book you’ll be delighting in for years to come.

***

Cathal Póirtéir is a writer and broadcaster who has published several books and CDs on Irish folklore, social history and literature in Irish.