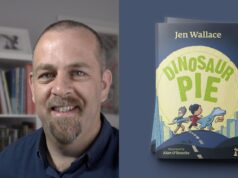

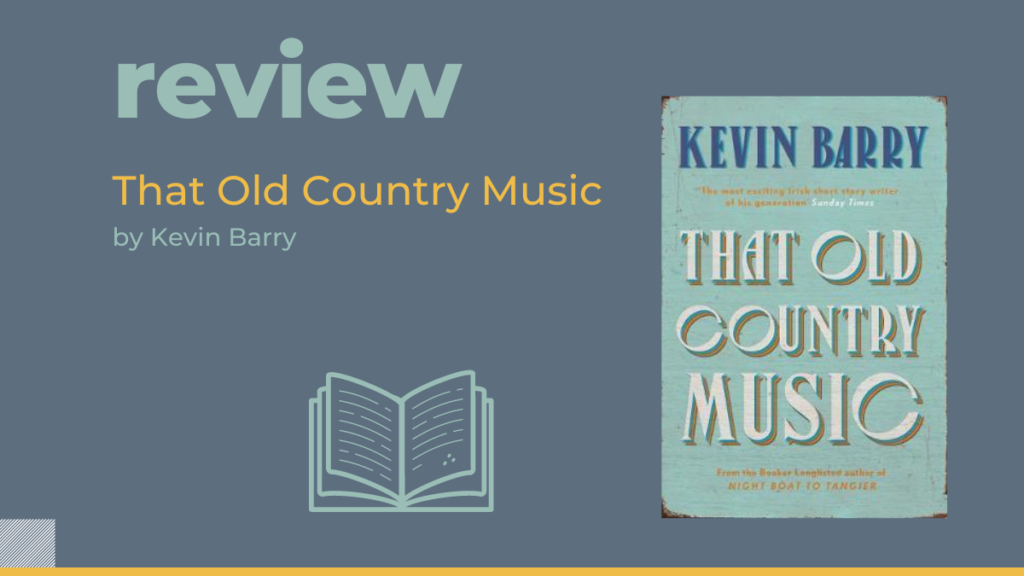

That Old Country Music

by Kevin Barry | Canongate | HB £14.99 | 9781782116219

Review by Stephen Reid

“Barry’s stories, unless you are catatonic, will have you laughing more page-for-page than most writers putting words to paper today.”

In Kevin Barry’s award-winning 2010 story ‘The Fjord of Killary’ our narrator tells us, sardonically, ‘I was the last of the hopeless romantics’. A decade on, and the standing army of Barry’s hopeless romantics seems far from depleted.

That Old Country Music,Barry’s newest collection—published this autumn by Canongate—resonates with the music of heart, the romantic impulse. Like narrative-driven ballads and laments, or the mythologies of folk-heroes, the stories carry familiar refrains and themes that seem to call and respond from one to another. The music here dilates between the heartsickness of American country, and the folk-ballads and keens of sean-nós. Open up a copy of the book and you may notice something immediately in the profile of the text; the book is typeset left-aligned (as are Barry’s previous books with Canongate) in the manner of poetry, in the manner of song lyrics.

Seamus Ferris, the emotionally tormented bachelor of the book’s opening story, ‘The Coast of Leitrim’, is afflicted—like so many of the characters in the book—by imagination, by mythologising and abstraction. To keep himself together while living alone, he tends towards the fabrication of scenarios, his desires and anxieties franticly unspooling below the surface of a staid and isolated life. Seamus’s imagination, which seems to have expanded in lieu of companionship, becomes malignant once he meets Katherine, a young Polish woman working at his local café. What was a defence mechanism for Seamus against loneliness becomes self-sabotaging.

The Irish Times recently noted that the new collection’s ‘best stories feel instantly canonical, as if we’ve already been reading them for years’, which may be because we have been reading most of them for years; the earliest story in the book, ‘Ox Mountain Death Song’, was published in The New Yorker in 2012, with eight more of the book’s eleven stories also published over the last eight years. Over that period, Barry’s writing has developed, and in his own words, he has changed too. He noted to The Paris Review that going back to older writing is ‘like visiting a ghost of yourself. We change all the time as people and it’s reflected so vividly in our prose styles. I mean, there’s nothing mysterious about your prose style, it’s a direct projection of your personality, the most direct projection possible.’ There has been a ripening in Barry’s writing of the last decade, a fluency with his themes, an ease with the romantic tendency. The mythologising, the heartsick and lonesome lovers, the lyrical passages tapered by a note of deadpan—these things were always there in his work, but the need for reflexive flips into irony or sardonic gestures has eased; the sentiments are often allowed to breathe more, while the signature tone still carries.

Canavan, the roving Sligo outlaw of ‘Ox Mountain Death Song’ is the archetypal folk-hero of the book, constructed as a mythological entity in the mind of his pursuer; he feels less like an individual than a blood-line, a cypher for any of the Canavans that came before him and any to come. ‘The Canavans – they had for decades and centuries brought to the Ox elements that were by turn very complicated and very simple: occult nous and racy semen.’ Sergeant Brown himself, Canavan’s pursuer over hill and dale, exists in the story as an individual, and also as a link in a genetic chain reaching back into the past. All of his forebears, we are told, drank themselves ‘into the clay of the place’. The tragedy of the story’s end seems like a requisite in the death song, which will continue down the generations to come, as ‘dark information rushed down the channels of the blood’.

The strongest stories in the book are generally written in the third person, a vantage Barry is a master of. Quite often, there’s a subtle percolating of the main character’s vernacular into the omniscient narrator’s voice, allowing for a certain signature Barry effect. Look at the adverbs in ‘Ox Mountain Death Song’ (‘sexily’, ‘fatly’, ‘greasily’) for example, which feel straight out of Sergeant Brown’s inner voice, and sing on the page with pitch-perfect humour.

‘Deer Season’, the story of a schoolgirl who is ‘almost eighteen and determined to have a fuck before it’, is arguably the masterpiece of the book, one of Barry’s finest pieces in any form. The story is a kind of inverted fable, with traces of Aesop where our characters flicker with an animal form—Edward, the lone Englishman living in the mountains near the unnamed girl’s home, brings to her mind a heron at one moment, while at the next his arm twitched madly under her touch ‘like a dog’s muscle’; his face ‘like a washed dog’. She, on the other hand, is vulpine, with her father watching her ‘as if it were a painted fox that crossed his yard’.

In the Nick Drake song ‘River Man’, which inspired ‘Deer Season’, a young woman visits the River Man twice, in the refrain of the song’s chorus, and by the song’s close Drake sings ‘If he tells me all he knows / About the way his river flows / I don’t suppose / It’s meant for me’. The young woman in Barry’s story is myth-making, fostering an experience that will act as a well for the artist she seems bound to become. In an interview with The New Yorker about the story, Barry noted that ‘in a way the story is a portrait of an artist in embryo—she has a vivid imagination, and she’s in that moment of haunted certainty that young artists experience when they discover who they are and what they’re going to do’.

There are somewhat weaker, less striking stories in the collection too, which tend to occupy the mid-section of the book. ‘Toronto and the State of Grace’ takes a familiar set-piece for Barry, the maudlin publican and the almost-empty country pub, and uses it to draw out a mother–son duo who tend to wax upon the theme of inherited behaviours and memory. The story may be less memorable, though it contains its share of staggering prose nonetheless: ‘The moving sea gleamed; it moved its lights in a black glister; it moved rustily on its cables’.

The story ‘Old Stock’ feels in ways like an early draft of ‘The Coast of Leitrim’; we find our lonely bachelor in a cottage inherited from a dead bachelor uncle.

The title story of the book, ‘That Old Country Music’, operates as something of an inversion of ‘Ox Mountain Death Song’. While the latter followed Canavan, the smouldering outlaw of the Ox, this collection’s title story follows Hannah Cryan, a young pregnant woman left waiting in the Curlew Mountains for the return of her fiancé, Setanta Bromell, a Canavanesque figure who has descended down the mountain to rob a petrol station with a claw hammer. We learn quickly that ‘it was not long at all since he had been her mother’s fiancé’.

The story is a wonder in careful dilation between memories of their brief passion, and recognition of imminent abandonment. We hear the refrain carry through the book again of inherited susceptibilities to the same vices and romantic ideas as our forebears. As Setanta rides away on his dirtbike, there is the sense of cycles being revisited, Setanta’s abandonment of the mother being re-enacted by the daughter. The tune is a familiar one, old as the hills. To Hannah Cryan, the song is bitterly familiar: ‘Her man in jail and a child at the breast – it was all playing out by the chorus and verse’.

The book ends with Theodore Roethke, and a masterful portrayal of the poet’s frenetic thoughts, a fractured narrative that glides between perspective vantages: ‘I could see Theodore in the third person’ the poet tells us, as he sits in an asylum in Ballinasloe, recalling his breakdown on Inis Boffin in 1960. Roethke is consumed by the idea of ambition, of constructing a self-mythology from his own feverish artistic ambition, even as he sits in the moonlight in an asylum in Ballinasloe, chatting to a psychiatrist. The final image we are left with? Roethke the poet, the writer, with his right hand lying ‘limply by his side but the index finger is busy and scratches quick patterns on the grey starched sheet – it makes words’.

Barry’s stories, unless you are catatonic, will have you laughing more page-for-page than most writers putting words to paper today. The question is, what’s the undercurrent running below the deadpan, below the fevered anxieties and insecurities of his characters; what’s Barry’s fixation? In his collection Dark Lies the Island, the word ‘love’ is mentioned 41 times. In That Old Country Music, it appears 44 times. Barry is a surveyor of the heart’s throes, of the blood’s quickenings and betrayals, of the ‘arbitrary music’ of our anxieties.

***

Stephen Reid works in editorial with New Island Books and sales with Brookside Publishing Services.