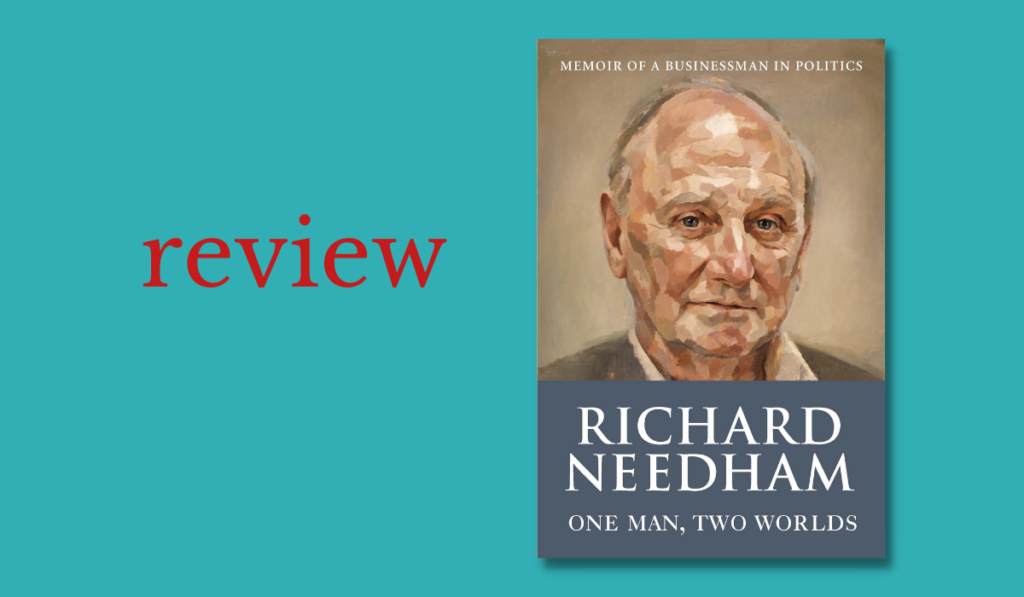

Richard Needham: One Man, Two Worlds|Richard Needham|Blackstaff Press|ISBN: 9781780733159|£14.99

Insightful and entertaining about the workings of the British government—Tony Canavan on Richard Needham’s autobiography

I have to admit to having personal experience of Richard Needham. My time as curator of the Newry Museum coincided with his tenure as Minister of the Environment in Northern Ireland.

Needham has a personal connection with Newry, being a descendent of the family that once owned the town and much of the surrounding country. He is the Earl of Kilmorey, with the secondary title of Viscount Newry and Mourne. This led to him taking an interest in Newry and ultimately to his donating the full regalia of the Most Illustrious Order of Saint Patrick, the state order of Ireland under British rule, to the museum.

He had inherited the regalia from the 3rd Earl of Kilmorey, who had been created a Knight of St. Patrick in 1890, making him one of the last knights of the order.

Despite being the order of Ireland, few museums here have any items associated with the Knights of St. Patrick, and not even the National Museum of Ireland has a full set of regalia. For a local museum like mine to acquire a full set was quite something.

On the day of the handover, I was asked to show Mr. Needham around the museum. He displayed a genuine interest in the collection and asked intelligent questions. I found an afternoon with this Eton-educated, self-confessed aristocrat, a not unpleasant experience. Later, when I published Frontier Town, an illustrated history of Newry, he took the trouble to write to me, pointing out where he thought I had been unfair on his ancestors.

However, there is little mention of Newry in this book, his third after Honourable Member and Battling for Peace: Northern Ireland’s Longest-Serving British Minister. Northern Ireland occupies some chapters, but it is only part of the Needham story. Its title refers to his two careers in business and politics. Needham was a moderately successful businessman and returned to business when he quit politics in 1997.

Despite being an Irish (as opposed to a United Kingdom) peer, Needham did not inherit land or wealth.

He can be amusing in talking about how useless his forebears were with money. Although clearly proud of his noble antecedents, it is clear that Needham is a self-made man. His experience in business converted him to the Theory Y style of management, instead of the traditional Theory X. He alludes to the difference between the two throughout the book.

Being an adherent of Theory Y made him a natural ‘wet’ in politics. Needham is happy to turn this insult from Mrs Thatcher about the left-wing of her party into a badge of identity. He had neither a meteoric nor stellar political career. He gives an entertaining account of trying to find a seat to run in, eventually ending up as MP for Chippenham in 1979 where he remained until his retirement from political life. It is clear that he is disappointed at never becoming a cabinet minister but he has the double distinction of being both the longest serving Northern Ireland minister and British Minister for Trade. Given the anecdotes that Needham tells, it is not surprising that he rose no higher.

The book is full of entertaining stories, usually with the joke on himself. However, insulting both Margaret Thatcher and John Major is probably not the best route into the Cabinet.

I was particularly interested in Needham’s account of his time in Northern Ireland. I found it a lesson in perspective. As a resident of Northern Ireland at the time, I find that my perspective differs from his. Despite his Irish connections, Needham usually refers to Northern Ireland as Ulster or the Province, terms which are inaccurate and which many find offensive. The reader gets an insight into the British mindset in that Needham saw his job as being to make Northern Ireland work, and views the main problem as being IRA violence. He makes scant mention of Loyalist terrorists’ violence or misdeeds by the security forces. Nevertheless, Needham comes across as well intentioned and clearly enjoyed being a minister there.

This book is a good read. Needham not only writes well but knows how to tell a story. He may be accused of blowing his own trumpet, but isn’t that what an autobiography is for? There are numerous anecdotes and insights into the workings of British government and subsequently business. The reader may not agree with the views expressed by Needham or accept his portrayal of himself but they will be entertained throughout.