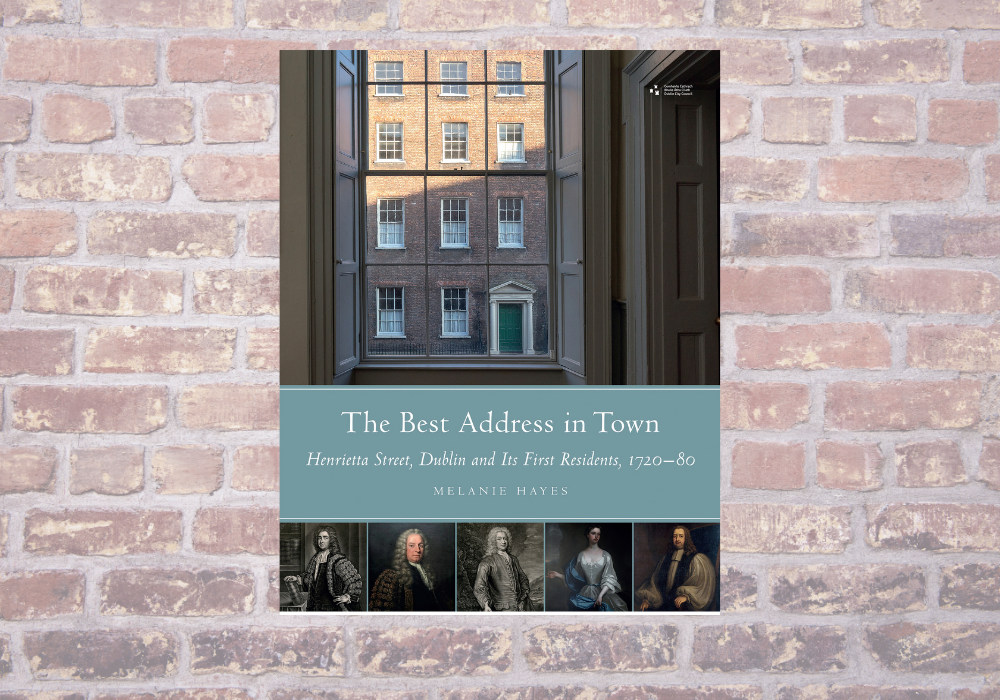

The Best Address: Henrietta Street Dublin and Its First Residents, 1720-80.

Melanie Hayes

Henrietta Street was Dublin’s first great Georgian street. Laid in 1720s by the private banker, politician, and property tycoon, Luke Gardiner, it was pioneering in its scale and grandeur, and set the standard for later Georgian developments throughout the city and beyond. The once-grand houses were palatial in size, rising a lofty four storeys over basement, with neat railed areas in front; carved stone door cases stood sentinel at street level, while large sash windows, set back into broad red-brick facades offered glimpses of the richly decorated and finely furnished spaces within. But to walk by today there is little hint—save the size of the buildings—at their former grandeur. In writing The Best Address in Town I wanted to recreate a sense of Henrietta Street in its heyday, to repopulate the houses with their original occupants and breathe life, once more, into the eighteenth century street.

Once Dublin’s most exclusive address, throughout the eighteenth century Henrietta Street was home to the country’s foremost figures from church, military and state. From social climbers like the Clementses and the Grahams, intent on establishing themselves on a broader stage, to politically-minded clerics like Archbishops Boulter and Stone, who regularly courted controversy for their unpatriotic views; ageing military men and senior statesmen such as Generals St George and Molesworth and John Maxwell, who despite their years pursued the ambitious agendas of much younger men, to political powerhouses like Speakers Henry Boyle and John Ponsonby. Here, in this elegant setting on the north side of the city, these influential individuals established one of the principle arenas of elite power in Georgian Ireland.

On the surface Henrietta Street’s residents were a close knit group, united by friendship, family ties, and shared political outlook. Something of an old boys club, cronyism was rife. The men joined the same clubs and societies, from the Freemasons to the Hellfire Club; they frequented the same taverns and coffee houses; and formed important and mutually advantageous political alliances, often during after-hours drinking sessions in the dining rooms of these houses. Yet beneath the convivial facade bitter rivalries and divisive political fault lines ran deep, with these close-knit networks splintering off into smaller cliques and cohorts, all intent on furthering their individual agendas.

But what about the women who held court behind the scenes? Henrietta Street was home to a number of noble heiresses, from Lady Henrietta Boyle to Lady Alice Moore, the Hon. Mary Granville and the Hon. Anne Stewart, these were women of great fortune but of whom little trace remains in history. Indeed in the case of the latter three women, not even a portrait or likeness survives. At this time no respectable woman would be mentioned in the public press, except in announcements of births, marriages and deaths, nor were their activities recorded in official sources. The intimate and everyday events of female life would of course have been closely chronicled in letters and diaries, but few of these have been uncovered to draw out their experiences. Yet, in the eighteenth century these wives, mothers and daughters played integral and often very visible roles in the running of elite households, with the mistress of the house successfully negotiating the blurred boundaries between the private sphere and the public world of their husbands.

A rare glimpse of this female perceptive is offered in Anne O’Brien’s memoir on married life, which brings wonderful colour to her story. Anne, or Nancy as she was always known, seems to have been rather besotted with her husband, Sir Lucius O’Brien, whom she refers to as ‘the best of men’ and she ‘the happiest of wives.’ She was constantly at her husband’s side, supporting him in his public endeavours, and when parted Sir Lucius pined for her company. ‘The truth is,’ he wrote, ‘my own Nancy has made home so dear to me that I do not find relish for places from which she is absent.’ Nancy was a loving but strict mother, who passed her pearls of wisdom down to her children through her journal, remarking on dangers of indolence, which her daughter Nichola was inclined towards, while her son Edward was ‘prone to self indulgence.’ All were to guard against ‘a waste of time as the bane of happiness.’ In fact, what struck me most about these women, and men, was the universal nature of their experiences, which transcend time and place. Someone like Lady Mary Molesworth, for example, a renowned beauty, who at age fifteen married a viscount some forty years her senior, might seem remote to us. And yet the same course of events: births, marriage and deaths, marked out the stages of her life. She too was anxious for the safe delivery and health of her children, particularly the spread of infectious diseases, while she and her husband were perhaps just as concerned as us about their own health, wealth and job security. By peeling back the layers of history, and exposing the lives lived within these spaces, the echoes of Henrietta Street’s past comes alive in the present.

- Available to purchase online via Four Courts Press and in all good bookshops .

- Commissioned by Dublin City Council Heritage Office in conjunction with the 14 Henrietta Street museum.