My Life In Loyalism|Billy Hutchinson with Gareth Mulvenna|Merrion Press|paperback| ISBN: 9781785373459|€18.95

by John Kirkaldy

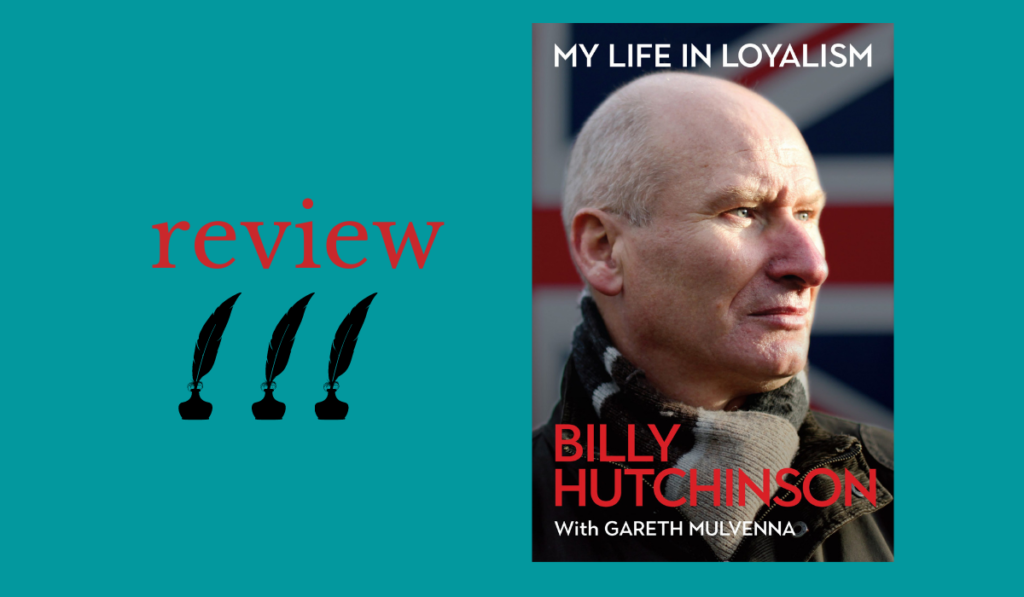

The picture on the front cover tells us almost all we need to know.

The eyes are determined, looking into the middle distance. This is a man of strong views, not given to going quietly; somebody whom you would like—instinctively— to be on your side.

Billy Hutchinson—Hutchie to most people—was born and raised in the loyalist heartland of Belfast’s Shankill. As a teenager, he grew up in the rising sectarian violence of the late 1960s and early 70s. In 1975, at the age of just 19, he was sentenced to life imprisonment for killing two Catholic men. In the cages of Long Kesh, he first came under the influence of loyalist icon, Gusty Spence. In the 1980s, he was for much of the time the Commanding Officer of the UVF (Ulster Volunteer Force)/Red Hand Commando prisoners. On his release in 1990, he became a leading figure in the Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) and a strong supporter of the peace process.

This book provides some important understanding of present-day Northern Ireland. It gives a vivid account of what it was like to grow up in a working-class loyalist area.

Although as Hutchinson came to believe later, there was little real difference between the backdrop for the loyalist and nationalist communities. ‘We were portrayed as the Protestant ascendancy, but that was a falsehood. It was the landowners and factory owners who were the ascendancy. We were merely the people who made them rich and kept them in furs and diamonds.’ The tribal identities, however, ran very deep, cultivated over many centuries: church, sport (Hutchinson was an avid Linfield supporter), employment, education, flags, symbols, parades, culture, housing and virtually every other aspect of life.

Hutchinson explains how he was drawn into the spiralling violence as a teenager. He became a member of the youthful Tartan gangs and then the Young Citizen Volunteers (YCV), the youth branch of the UVF. (Is there any place in the world where there are more acronyms than Northern Ireland?) Soon he graduated to the UVF. With dwindling prospects and little education, the violence provided identity and excitement. ‘I saw an opportunity to do something that would get me and my friends noticed.’ He remembers reflecting at the time, ‘I’m still at school, and the police and the army are looking for me.’

His account of events up to his imprisonment is vivid, compelling and partisan. It is very unlikely that many readers will agree with all of it.

I cannot remember any collaborator, writing as Gareth Mulvenna does in the preface: ‘I don’t and can’t agree with everything that Billy has done in his life, and he would not want me to…there are many events in this book which I do not endorse or support.’ In March 2014, for example, in an interview with the Belfast Telegraph, Hutchinson is quoted as saying that he had ‘no regrets’ about this part in relation to the random murder of his two Catholic victims in 1974, claiming that he had helped prevent a united Ireland by his actions.

Prison changed Hutchinson in two very important ways. First, influenced by Spence, he began increasingly to feel that, despite their vast differences, the two groups of paramilitaries had a lot in common, not just incarceration. His perception of events was greatly influenced by his study in prison, especially for an Open University (OU) degree. (I must declare an interest here, as an OU history tutor for 37 years, which involved in part working with prisoners in England and Ireland.)

Hutchinson became an important link between the UVF and the PUP. He was heavily involved in the Belfast Agreement and the decommissioning programme. He considers himself a socialist and an atheist; he is also a fitness enthusiast and a teetotaller. He was never a member of the Orange Order. He has stood for election for the Northern Ireland Assembly (he was member (MLA) for Belfast North, 1998-2003) and is currently a City Councillor for the Court Ward. Being a political activist in Northern Ireland is not the same as elsewhere in the United Kingdom. Between his release from Long Kesh to his election as an MLA, death threats were a regular occurrence, ‘I’d been subject to about thirty-two.’ Most of these ‘came from republicans, but in the years surrounding the Belfast Agreement, I began to receive more from loyalists.’

Although his politics have adapted and changed, he still states his views in a forthright fashion. Ian Paisley, for example, comes in for repeated hostile comments. My dad warned me to stay away, telling me that Paisley ‘would fight to the last drop of everyone’s blood.’ How prophetic.’

Northern Ireland is currently teetering on the brink of a serious lapse back to the Troubles. It needs more people to look to the middle distance. Hutchinson is proof that the past can be put behind, even though it cannot be changed, and a better future envisaged.

In a 2020 interview, he stated, ‘I justify everything I did in the Troubles. To stay sane, I have to.’ But who would have thought that the teenager, who made his reputation as a stone throwing protester, would later act as a peace maker between infighting loyalist groups? Or would put out a guarded but sincere hand to republicans?

Billy Hutchinson is clearly no saint but the hope is that with a past like his, it demonstrates that change and adaption is possible. He writes, ‘I want people to understand that if it had not been for the toxic atmosphere created in society here, young men like myself would never have seen the inside of a prison…I would like to think that the next generation will continue to live normally, without the backdrop of violence. I hope in telling my story, that I have contributed to a better understanding of the Troubles and the role that young loyalists played in it, so that we must never repeat those violent years.’

John Kirkaldy has a PhD in Irish History, worked for many years with the Open University and has been reviewing for Books Ireland since 1980. He has contributed to three Irish history anthologies, a school textbook, and has been involved in a number of Open University History documentary series. Aged 70, two years ago, he went round the world on a much delayed gap year described in his book, I’ve Got a Metal Knee: a 70-Year Old’s Gap Year.