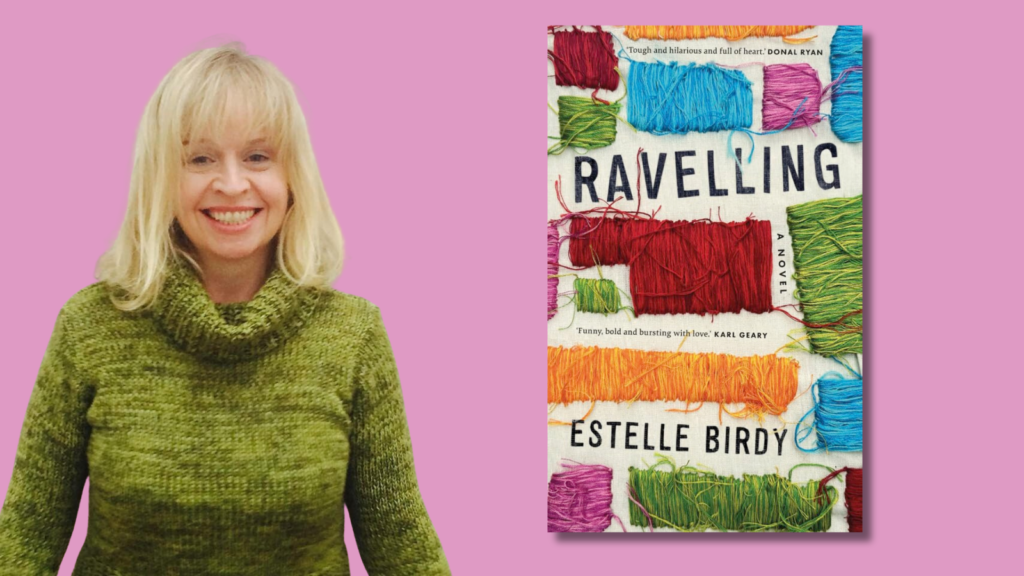

Ravelling|Estelle Birdy|The Lilliput Press

Estelle Birdy talks with Niall McArdle about words which have built a world

by Niall McArdle

Estelle Birdy‘s bright, open face beams at me over Zoom. It’s a Saturday afternoon in early May and she’s visiting her father in Louth. “Louth and Proud!” she exclaims even though she’s lived in Dublin since she moved there for university.

Her debut novel, Ravelling (The Lilliput Press) set in the Liberties where Birdy lives and writes, tells the story of five teenaged friends on the cusp of adulthood. It’s a pacey, bleakly funny, warm and compassionate novel and is filled with hilarious, inventive, sweary dialogue reminiscent of Roddy Doyle. Like Doyle, Birdy has a canny ear for the way people speak. Was Doyle’s writing an influence? “I love Roddy Doyle’s writing. He’s just a master of dialogue and dialect. But It’s more his love of people [that I admire]. You know even when you see him interviewed, it’s just flowing out of him; like, his eyes are dancing when he’s just talking about people. And that’s the way I feel about people, too.”

It’s a pacey, bleakly funny, warm and compassionate novel and is filled with hilarious, inventive, sweary dialogue

Birdy’s empathy is similarly clear. One of the initial sparks for the book came one winter evening when she was chatting with a homeless man on St. Stephen’s Green, and a teenager, “in the full uniform: body warmer, tracksuit, white socks pulled up, the fade and everything, and this young guy dropped a load of change and didn’t break stride and walked on.” Birdy noted that it was a lot of money for a kid to have and the man told her it was always the young fellas that would stop and be the most generous with him.

This generosity of spirit struck her: that there are probably young men like him all over the city, and while most people might stereotype them as dodgy or to be feared, Birdy, who’s also a yoga instructor, noticed his body language: “He was doing everything to make himself small, he didn’t want to be seen.” Her own son was around the same age and his friends from school would be in her house. “All these young fellas were around me all the time, and they’d be telling me stories, and I’d be listening in, and they were having these really quite deep conversations, and they were really funny.”

She met others through teaching yoga at Casa Rehab Centre. “I’d be meeting young men from all walks of life and it would make me really angry that some of them would end up shot in the back of the head in some pub and it was always reported as ‘so and so was known to Gardaí’ and that was code for ‘that’s the end of it; you don’t need to give a shit about this person.’”

In Ravelling, Birdy seeks to show that these teenagers have a depth to their lives, and the diverse cast of characters are extraordinarily well-drawn

In Ravelling, Birdy seeks to show that these teenagers have a depth to their lives, and the diverse cast of characters are extraordinarily well-drawn: Deano, the weed-smoking hurling star trying to steer clear of a local ganglord; Hamza, the Pakistani Muslim atheist who sells drugs to private schoolkids; Oisin, who frequently sees the ghost of his dead brother; Benit, the Congolese immigrant; and Karl, the maybe-gay fashionista. The scenes are fast-paced and brimming with slang-filled dialogue.

—Where’s Candy, I wonder? Benit says.

—Probably back there in the kitchen, Karl says.

—Would yeh? Oisin asks

—Fuck off, no! Deano says. The state of her. Would have, obviously. But she’s fucken tapped.

—I would. She’s still a ride, Oisin says. Looper or not.

—Peng ting, Benit says, eyes closed, nodding.

—Peng ting! She’s fucking manky, Deano says. She was just riding her brother’s coffin for fuck’s sake! You don’t even get with white girls, Benit. What are yeh on about?

—Still recognise a sweet one, fam, no matter how devoted I am to the sisters, Benit says, blowing a kiss into the air. Bunda too, innit?

Birdy’s background is as a socio-linguist. “I just love dialect and the way people speak and the codes. I can feel my eyes lighting up when I hear people saying something that’s just so much fun, and they’re playing with language, and I think Irish people do it really freely. And young people, Dubs especially, they do it all the time. They’re tricking around with the language, and they’re really articulate, you know, making up words.”

During the writing of the novel, she would consult her teenaged children and their friends to ensure the dialogue rang true, and that the novel’s multicultural, multi-ethnic milieu was accurately depicted. “I call them the Technical Team: they’d be in the house and some of them would only give me, say, one key piece of information and go ‘no, that’s not what happens’ or whatever, but some of them were really involved for long periods of time.”

They’re tricking around with the language, and they’re really articulate, you know, making up words

Birdy is reluctant to describe the setting as multicultural. “It says that on the blurb, and of course it’s a handy word, but it’s not really multicultural Dublin; it’s just Dublin culture.” The characters gleefully hurl racial insults at each other, and while some readers might find it politically incorrect (a term Birdy hates), she says it’s an accurate reflection of real life.

It says that on the blurb, and of course it’s a handy word, but it’s not really multicultural Dublin; it’s just Dublin culture

“The actual multiculturalism, the banging the heads together, the absorption of culture, that’s actually going on in working-class communities, that’s where it’s really happening.”

We discuss the Irish Writers Centre Novel Fair, about which she can’t say enough good things. “It’s exceptional. I don’t think there’s anything anywhere else quite like it. Even for the practice of getting to pitch to publishers and agents.” The fair’s pitching process “was right up my street. I used to be in recruitment, and I’m from a long line of cattle traders. I try and haggle in Brown Thomas,” she says, laughing. Ravelling was a winner at the fair in 2020, something of a vintage year (other work being pitched that year included Laura McKenna‘s Words to Shape My Name; Olivia Fitzsimons‘ The Quiet Whispers Never Stop; Alison Wells‘ The Exhibit of Held Breaths; and Miki Lentin‘s forthcoming Winter Sun).

The deal with Lilliput followed in a matter of weeks, but publication was delayed by the pandemic. “I was the first person signed, and the last person published,” she jokes. In fairness, she adds, the book wasn’t really finished at that point, and being stuck at home wasn’t conducive to working on it. “The lockdown was terrible for me. Even now my world is a bit shrunk from it. I know lots of writers had a good time in lockdown, it really suited some, but for me it was the total opposite.”

In 2018 she did the Master’s in Creative Writing in UCD and she credits that experience with making her a writer

It was strange, she says, to be writing about people getting together and going to school and parties and living a normal life when she couldn’t do the same. “Not to have that energy and buzz, not being able to go out and hear conversations and listen to all different types of people; it was so tough not to have that. And seeing things, too. The Liberties is such a lively area, but of course during lockdown it was very quiet.”

Birdy has been writing all her life, from early childhood on, and always assumed she would become a writer even though, as she says, she was unsure how exactly to become one. She studied Law at UCD and later worked in recruitment and as a freelance writer. She wrote marketing and communications for various companies, as well as pieces for other people’s blogs, but it wasn’t until 2011 that she started submitting stories to competitions. In 2018 she did the Master’s in Creative Writing in UCD and she credits that experience with making her a writer.

I need a good kick up the arse every now and again. I’m very good at taking criticism. If it’s necessary, I want to hear it

It was a dialogue exercise from Declan Hughes that got her going on what would become Ravelling. “I’d never written dialogue like that, but it just came out, I suppose because I was surrounded by it from kids. It just wrote itself […] I can hear their voices; I can see them, too.” She heaps praise on Declan Hughes and the other tutors at UCD, especially Sebastian Barry, who urged her to explore the story of these boys that she was writing about. “He said to me, ‘you have to write this.’”

She’s equally effusive about the novel’s editor, Colm Farren. “His nickname is The Hammer because he’s so exacting, so severe, but honestly it was just a literary marriage made in Heaven. He completely knew how to deal with me, how much pressure to put on and not put on. I would often tell him he was being too nice. I need a good kick up the arse every now and again. I’m very good at taking criticism. If it’s necessary, I want to hear it. It really helped just having him there like because there would be acres of time where I was just sitting there looking at a wall for weeks not writing a thing.”

Was the editing process difficult? Was there a lot of killing your darlings? I ask. She gives a rueful smile and sighs. “I’ve killed so many of my darlings, I’ve actually wept. Colm and I would be sending chunks of the book back and forth and we did some really high-speed, intense editing where we were meticulously redrafting.” She lost count of how many drafts there were. The original word count was 170,000; it’s now roughly 110,000. “There were so many brilliant scenes that were really important to me that ended up on the cutting room floor, but they just had to go.”

Birdy will be involved in the TV adaptation, but is hesitant to say too much about it

Ravelling has been optioned for a TV series. I suggest that some of those cut scenes could get another life. “Yes, actually, for example, there’s an entire scene with Karl and the prospective director wants it back in.” Her eyes light up at the thought of resurrecting some of the darlings she killed. Birdy will be involved in the TV adaptation, but is hesitant to say too much about it. It’s at the outline stage at the moment but the plan is for it to be three seasons, allowing for more of the story and the world of Ravelling to be explored. “We are actually quite far along with it, it’s not just been sitting on a shelf.”

When I ask about her writing process, she laughs. “There is no writing routine. It’s mostly not writing. But then at times there’d be really intense periods where it was ten, twelve-hour days, but then often there’d be days when I was just walking along the canal going through it in my head. So many times I find myself talking to myself and I only realise that when I see the horror or laughter on somebody’s face.” At the moment she is planning her second novel. “It just came to me a few weeks ago what it will be, and what the shape of it will be. It will be very different to Ravelling; it’ll be a two-hander. Two women.”

As we come to the end of our chat, talk turns to writers and books that have had a big influence on her. She cites Umberto Eco‘s Name of the Rose as a favourite. “I wasn’t okay for about a month after reading that. I was bereft. When I finished it, I cried.” She actually read it before studying linguistics but the codes and the semiotics appealed. She seems to be drawn to long books and world-building, mentioning Jose Saramago‘s Blindness, Snow by Orham Pamuk, and White Teeth by Zadie Smith. “I loved the sweep of it, I loved the humour, and Anna Burns‘s Milkman blew me away. The language of it, the darkness. It’s really dark and oppressive but it’s so filled with humour, too.”

Our time has come to an end. I wish her the best for the book and the TV show. There’s another beaming smile. “Yes, fingers crossed, I’m lighting the candles,” she jokes.