Partition: How and Why Ireland Was Divided|Ivan Gibbons|Haus Publishing|ISBN:9781913368012|£12.99

Extract from How and Why Ireland Was Divided, by Ivan Gibbons (Haus Publishing)

A British Perspective

From a British perspective, the partition solution establishing two Irish parliaments took Ireland out of the realm of British politics, allowing Britain to withdraw from Ireland on her own terms.

Elections for the parliament of Southern Ireland on 24 May 1921 became elections for the republican assembly, the Second Dáil, where Sinn Féin were unopposed in 124 out of 128 seats. The parliament of Southern Ireland met only once (with four unionists), was adjourned sine die and was ultimately disbanded by the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act 1922. It ceased to exist on 6 December 1922 when the Irish Free State constitution legally came into existence.

The thinking was that because the Irish could now govern themselves, no Irish person could ever again complain about domination from Westminster.

All Ireland was now autonomous, and the eventual reunification of Ireland (a particular concern expressed by Britain’s allies the United States and the Dominions) could be facilitated on an agreed basis in accordance with the topical principle of self-determination established recently by the Treaty of Versailles. Even with the benefit of a century of hindsight, it is difficult to imagine an alternative option to partition that would have made sense from the British perspective, if their overriding concern was to withdraw from Ireland without coercing Ulster.

If the Home Rulers rather than Sinn Féin had still been the dominant political force in the south, the Government of Ireland Act would have been a brilliant solution. All previous Home Rule had foundered on the rock of unionist opposition. Ironically, the Fourth Home Rule Bill satisfied Ulster (or most of it) but not the extreme nationalists of Sinn Féin, who were the new masters in the south where, as described above, the Government of Ireland Act remained dead amid escalating and relentless political violence. The Act was, however, the only one of the four Home Rule Bills to come into effect, even partially.

In this it reflected the new Tory-dominated balance of power at Westminster, but it is an irony that the only part of Ireland not wanting Home Rule was the only part to get it.

Conservative perspective

From a Conservative perspective it was obvious as early as 1917, if not before, that an Irish settlement involving some sort of Home Rule was essential to the war effort and to bring the Irish-American lobby into the war – and was probably necessary to ensure the survival of the Empire after the war, given the concern and anxiety shown by the Dominions towards Britain’s Irish policy. It is also apparent that Conservative support for the Ulster unionist case weakened between 1913 and 1918 – undoubtedly because since 1916 the Conservatives had been the dominant partners in the wartime coalition government and so no longer needed to ‘play the Orange card’, that is, to align with unionists in Ireland for political gain in the quest for office. Furthermore, as the Irish crisis intensified it became increasingly obvious to both parties that although their short-term interests might coincide, the Conservatives were ultimately concerned about the future post-war welfare of the United Kingdom as a whole, whereas the Ulster unionists’ overriding concern was for their own identity in Ireland.

Labour Party attitudes

Labour Party attitudes to Ireland were also changing. Prior to and even after the war, the Labour Party had provided general, vague and unthinking support for the political demands of moderate Irish nationalism. It became clear, however, that if the Labour Party aspired to become the governing party in the British state, it had to distance itself from the revolutionary politics that had rapidly come to dominate Irish nationalism since 1918.

Unlike the Conservatives, the Labour Party had no political debts to pay in Ireland.

There had never been a cohesive and logically planned Irish policy in the Labour Party. For historical reasons nearly all the party (except in Belfast) had a deep and genuinely held emotional attachment to the moderate policies of the Home Rulers. Labour shared the Home Rulers’ abhorrence of partition as a threat to the territorial integrity of Ireland. Consequently, Labour opposition to the Government of Ireland Act provided certainty to its supporters and voters at a time when its own policies on Ireland were in a state of flux, as it was increasingly criticised for slavishly following the traditional Home Rule policy when it was obvious that mainstream political demands in nationalist Ireland had moved well beyond that. Inevitably the party’s cautious constitutionalism and parliamentarianism began to be threatened by its more radical members and some (although not a majority) of its Irish voters in Britain, who demanded direct action and a closer identification with the extra-parliamentary nationalism of Sinn Féin.

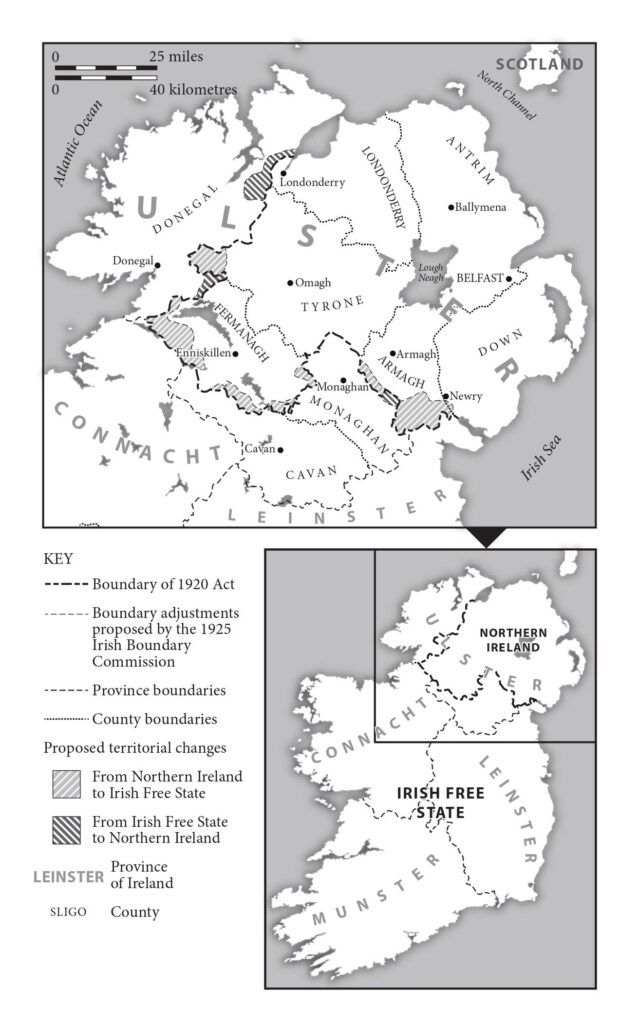

The Irish border

The Irish border demarcating the six counties of Northern Ireland from the rest of the country became a reality on 3 May 1921.

Ironically, it first of all separated a Home Rule Northern Ireland from the bulk of the island that was still run directly from Westminster.

Initially, Ulster unionists had been suspicious of the offer of a separate parliament in Belfast, fearing that it was some sort of dastardly ploy to detach them from the rest of the United Kingdom by treating them as semidetached members who at some stage in the future could be delivered into the jaws of an all-Ireland state. They quickly warmed to the idea, however, when they saw that a separate parliament for Ulster, permanently controlled by unionists and in charge of their own security, gave them added insurance against peremptory expulsion from the United Kingdom in the future. From then on, all the political energies of the unionists would be directed into maintaining the border that had come into existence that spring.

Partition: How and Why Ireland Was Divided|Ivan Gibbons|Haus Publishing|ISBN:9781913368012|£12.99

IVAN GIBBONS is a lecturer in Modern Irish and British history specialising in the relationship between the British Labour Party and Ireland. He was lecturer and MA and BA Programme Director in Irish Studies at St Mary’s University. He is the author of The British Labour Party and the Establishment of the Irish Free State (2015) and Drawing the Line: The Irish Border in British Politics (2018).