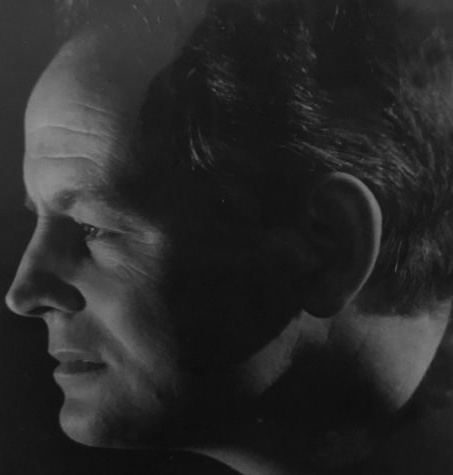

We are saddened to hear of the death of Ulick O’Connor, aged 90. Although an eminent literary figure, he was also a controversial one who never shied away from publicity and whose utterances often caused outrage. O’Connor was proud of the fact that his family formed part of the elite of the early Irish Free State, but he himself became an admirer of Charles Haughey, who as Taoiseach appointed him to the board of the Abbey Theatre. He was born in Dublin in 1928, the first child of Prof Matthew O’Connor, of the Royal College of Surgeons, and his wife, Eileen (nee Murphy). Educated at St Mary’s College, Rathmines, he studied philosophy at UCD and took his degree in 1949. He was called to the Bar in 1951 and practised as a barrister for 15 years. He completed a diploma in dramatic literature at Loyola College in New Orleans, while attending the law school there. He then dedicated himself to becoming a writer.

Oliver St John Gogarty – portrayed as Buck Mulligan in Joyce’s Ulysses – launched O’Connor’s literary career by appointing him his biographer. An appearance on the Johnny Carson TV show started him on the profitable US lecture circuit. At home he was a regular guest on Gay Byrne’s The Late, Late Show and other RTÉ programmes. When the Northern Troubles began, O’Connor spoke up for Northern Nationalists at a time when the prevailing view in the South regarded Republicans as no more than terrorists. He respected Bobby Sands, the IRA man who died on hunger strike, and was among those who delivered a petition to the British embassy in Dublin on 18 July, 1981, an occasion which ended in violence.

As a writer, he produced biographies, verse plays, and poetry. He was appointed to the board of Abbey Theatre in 1982 and was later elected a member of Aosdána. O’Connor was not afraid to tackle controversial subjects in his writing. He penned an introduction to Bobby Sands’s poetry collection Skylark Sing Your Lonely Song, while his Civil War play, Executions, confronted some uncomfortable truths of that period in Irish history and caused much controversy at the time. Of it, O’Connor wrote: “A decolonised people inherit many confused conditioned reflexes from centuries of being governed by an imperial power. The working of these reflexes out of the national mind is a painful process and, it would seem, a long one.’’ Celtic Dawn: A Portrait of the Irish Literary Renaissance, published in 1984, took him eight years to write. It portrays the literary revival through the biographies of seven leading figures. That book won him the Irish-American Cultural Institute’s English-language literary award in 1985. Of his legacy, he once said that he hoped to be remembered “as having written one good poem or one good book that would outlast me’’.