Madeleine D’Arcy talks all things books in the companion series to our popular podcast Burning Books.

Her new collection of short stories Liberty Terrace is just out with Doire Press.

What books would you save if your house was on fire?

A book you return to over the years?

I have read and reread all of Elizabeth Strout’s books. Olive Kitteridge is probably my favourite – and the HBO mini-series is wonderful too.

I have also often returned to Claire Keegan’s second short story collection Walk the Blue Fields (Faber & Faber, 2007). I particularly love the title story. The scenes at the wedding are full of humour and brilliant dialogue, and they serve to heighten the reader’s sympathy for the main character, an Irish priest who has been obliged to officiate at a wedding ceremony, whilst suffering from unrequited love.

The right book at the right time?

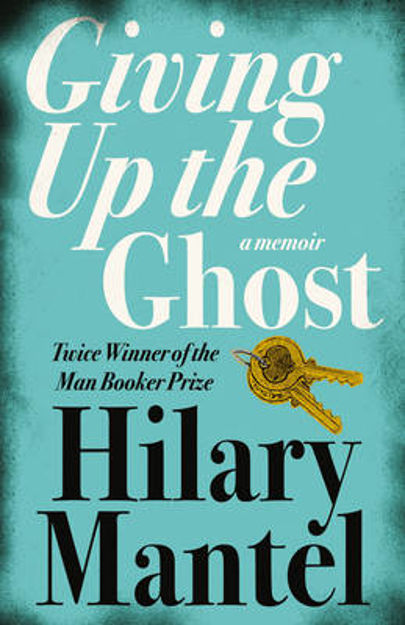

Hilary Mantel’s memoir, Giving Up The Ghost (2003, Fourth Estate) is a beautifully written book. She suffered from severe endometriosis and reading about her experience was a great comfort to me, because I knew only too well what she was writing about.

I also suffered from Stage IV endometriosis. It is an incurable and very painful disease and there is no permanent cure. If men suffered from endometriosis, I feel sure there would be a cure by now.

A book that taught you something important?

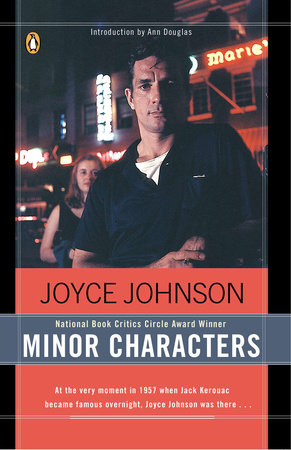

Minor Characters (1983, Picador) by Joyce Johnson, is a beautifully-written and very sad book. It’s not just a personal memoir about the 1950’s Beat Generation and the author’s brief relationship with Jack Kerouac but also an honest story about how it felt to be a young woman at that time.

The men strutted around and posed, gaining kudos and literary repute, while the women, equally talented if not more so, had a much more difficult process of ‘becoming’. Joyce Johnson seems to have managed to retain her self-worth and independent spirit, and emerge clear-eyed and relatively undamaged, but this was not the case for some of the other women in the same milieu at that time. As Angela Carter says on the back cover of my copy: ‘This is the muse’s side of the story. It turns out their muse could write as well as anybody.’

A book that makes you laugh?

The Inimitable Jeeves by PG Wodehouse, first published in 1923, never fails to entertain me. Essentially, it’s a linked short story collection. One of my favourite stories in this book is ‘The Great Sermon Handicap’.

I listened to a lot of radio versions of PG Wodehouse’s books during the worst months of lockdown and they reduced my stress considerably. His books are beautifully written and incredibly funny.

Modern readers may sniff at the popinjays in PG Wodehouse books, who are often in need of cash but rarely do a day’s honest work, but the predicaments they get into are laugh-out-loud funny.

Wodehouse got into trouble for doing German radio broadcasts after a period of internment in France during the Second World War and I have always felt very sorry that his later years were blighted by this fact. It seems to me that he was simply naïve, and did not intend to endorse the Nazi regime in any way.

After all, this is the writer who created Roderick Spode, 7th Earl of Sidcup and the leader of ‘The Black Shorts’, clearly a put-down of Fascism, so it is difficult to understand why people thought he was a traitor, and why he became so derided in his own country. However, his attempts to leaven his experiences of imprisonment by using humour backfired disastrously. After the war, he never lived in England again.

What are you reading now?

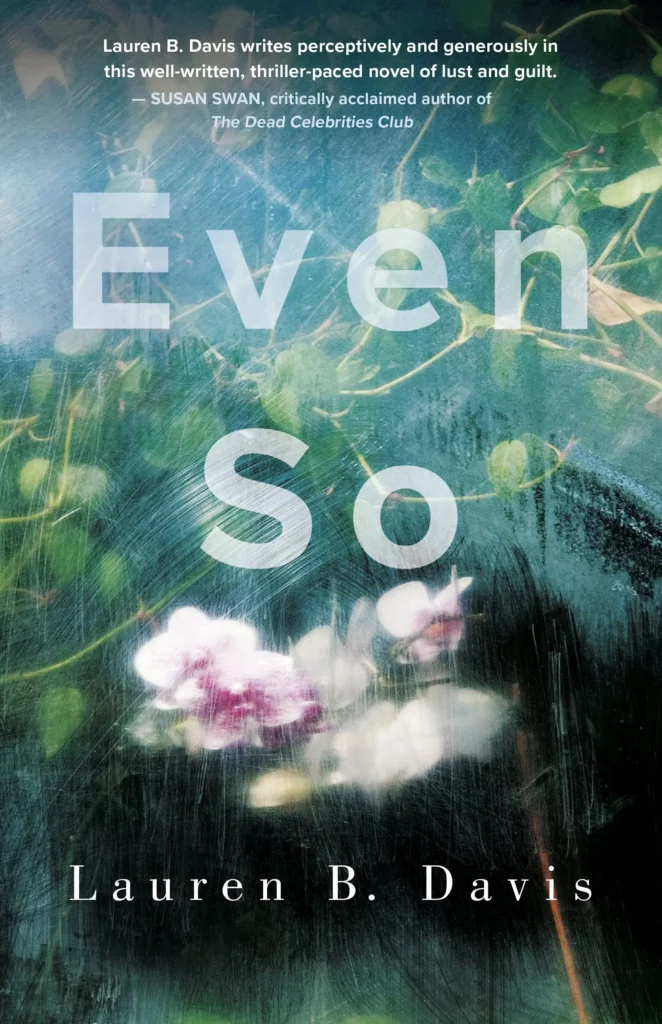

I’m currently re-reading a book called The Stubborn Season (HarperFlamingo Canada, 2002) by Lauren B Davis, an author born in Montreal, now living in the US, while I wait for her latest novel to arrive in the post.

Her new novel, Even So (Dundurn Press, September 2021), explores what it means to love other people – even the selfish, careless and difficult ones. The title comes from this poem by Raymond Carver, a poem I like very much:

Last Fragment

And did you get what you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved.

To feel myself beloved on the earth.

I’m fascinated by the fact that though each of Lauren’s eight novels is very different in terms of character, structure and setting, all of these very different fictional worlds she creates are engrossing and believable. For example, The Empty Room(HarperCollins, 2013) is an extremely funny and desperately sad novel about a 50-year old woman who has to face the fact that she’s an alcoholic.

In contrast, Against a Darkening Sky (ChiZine Publications, 2015) is set in 7th Century England and The Grimoire of Kensington Market (Wolsak and Wynn Publishers Ltd, 2018) is set in a magical version of Toronto. Yet, though each novel is different to the last, they all contain humour, compassion and empathy.

A book you’d leave in there to burn…

Long ago, when I was in secondary school, we were all obliged to read a book called Peig, in Irish, which was then on the curriculum. Peig is the autobiography of Peig Sayers, a woman who lived on Great Blasket Island during the late 19th and early 20th century. For me, this was an unrelentingly depressing read. I began to associate the learning of Irish with poverty, misery and boredom. I have never wanted to read anything in Irish since.

A book from childhood

I must have been three or four years old when I was given a book by Mabel Lucie Atwell (1879-1964), a British author and illustrator known for her cute nostalgic drawings of cuddly children.

The book consisted of an old English nursery rhyme, designed, I later realised, to teach children the days of the week.

Hence the first page stated that ‘Monday’s Child is Fair of Face’ and was illustrated by a beautiful, bonny, pink-cheeked little girl in a sweet dress. The next page, ‘Tuesday’s Child is Full of Grace’, featured a similarly delightful child. ‘Wednesday’s Child is Full of Woe’ had a picture of a cherubic child in floods of tears. At least I wasn’t born on a Wednesday, I thought. The whole thing struck me as being highly unjust. The message for Thursday’s Child was enigmatic and vaguely frightening: ‘Thursday’s Child has Far to Go’.

The illustration was of a plump, sweating, miserable little girl on a bicycle, struggling to pedal up a hill. This worried me. I was born on a Thursday. This did not bode well for my future. My life would always be an uphill struggle, obviously.

I tried to console myself that I wasn’t Full of Woe like the Wednesday kids. ‘Saturday’s Child Worked Hard For a Living’ and the harried-looking toddler on this page also made me anxious; I was glad I’d escaped that fate. ‘Sunday’s Child was Bonny and Blythe and Good and Gay’; she seemed like a pain in the butt. The book troubled me greatly until my mother explained that it was only a poem, not a law about predestination. I really, really disliked this book.

Short stories you would rescue?

It’s Beginning to Hurt by James Lasdun is a fine example of a very short story.

The Bear Came Over The Mountain by Alice Munro is a wonderful long short story.

For Esme with Love and Squalor is a story by JD Salinger which makes use of time in an unexpected way but still works.

I love short stories, and the above are fine examples of the form.

Liberty Terrace, Madeleine D’Arcy’s collection of short stories is out now with Doire Press.