“The memory of endeavouring to perform direct mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on two cold, lifeless, unknown, unshaven seamen, laid out on a rolling, heaving, windswept, spray-lashed deck in the darkness of a February dawn is not easily forgotten.”

An extract from Island Boy by Des Lavelle

Once upon a time, I thought that the Valentia lifeboat of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution could not get on without me. But time itself took care of that illusion, and the lifeboat service in Valentia is still very much alive and well, long after my departure from that young man’s scene.

Once upon an earlier time, though, in 1956, it seemed that the local lifeboat station might have to close for lack of crewmen, and in response to a general appeal, I became seriously involved for the first time, eventually progressing from the lowly status of seasick deckhand of the late 1950s to the more taxing duty of Second Cox’n from November 1969 – and onwards into the 1980s.

Overall, it was a window into another aspect of island life; there were lessons to be learned, and the earliest were the hardest.

Early lessons

One of those early lessons came at 12.45am on 7 February 1959. The French trawler, Marie Brigitte of Concarneau, ran into the Foze Rock at the extremity of Kerry’s Blasket Islands and sank within fifteen minutes.

It is easy to know now that the position relayed to Valentia lifeboat – ‘Three miles south of the Blaskets’ – was misleading. In local parlance, that term could indicate anywhere south of the Great Blasket.

Not until dawn of the following morning did we learn that the Mayday call referred to ‘three miles south of the Blasket lighthouse’– Inishtearaght.

The other French trawlers that hastened to assist read this location correctly from the outset, and only when they began reporting debris near the Foze Rock did the location of the disaster-site become clear to all searchers.

Real-life horror

Eventually, we picked up two bodies – roped together with makeshift life-jackets of net floats. The memory of endeavouring to perform direct mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on two cold, lifeless, unknown, unshaven seamen, laid out on a rolling, heaving, windswept, spray-lashed deck in the darkness of a February dawn is not easily forgotten.

All the textbooks we had read, all the lessons we had shared in water-safety classes conveyed nothing – absolutely nothing – of the real-life, nauseating horror of the situation.

On 6 July 2017, a French gentleman who had been only four years of age when his father died in that Marie Brigitte disaster, almost sixty years before, came with his family to pay a visit to the Valentia Lifeboat Station and to place a memorial wreath on the sea by the Foze Rock where we had picked up his father’s body in its makeshift life-jacket in February 1959.

Failed mission

The loss of the Irish trawler, the Sea Flower of Castletownbere, at the mouth of Ardgroom harbour in Kenmare Bay, at 1.21am on the morning of Sunday, 22 December 1968, was another failed lifeboat mission.

We now know that the Sea Flower had gone down even while we in the lifeboat, Rowland Watts, were still some ten miles short of the disaster area; and I shudder just to wonder what we could possibly have achieved anyhow in the foaming cauldron that was Kenmare Bay on that occasion.

The sea conditions on that night have gone down in my memory as totally dreadful.

The 33-mile journey was bad enough, but the worst moment of the storm would hit Kenmare River, outside Ardgroom harbour, at dawn on the following morning.

The lifeboat mounted a wall of water and literally fell into the next trough. It fell and fell, almost to the bed of Kenmare Bay some 20 metres below – there to be totally buried in water and green darkness as the following breaker crashed down.

A crucial lesson

Five good men were lost with the Sea Flower, but the sad event also offered a lesson.

Long before the alarm was finally raised, there had been indications that something was amiss, and had the lifeboat, or the trawler Árd Béara that also came to assist, or other search-and-rescue services received timely notification, the outcome just might have been different.

The clear lesson to be learned is this: when there is ‘something wrong with the picture’ in seafaring situations, it is better to alert the appropriate agencies in good time – better to risk the embarrassment and the nuisance of a false alarm rather than say nothing and allow a disaster to develop.

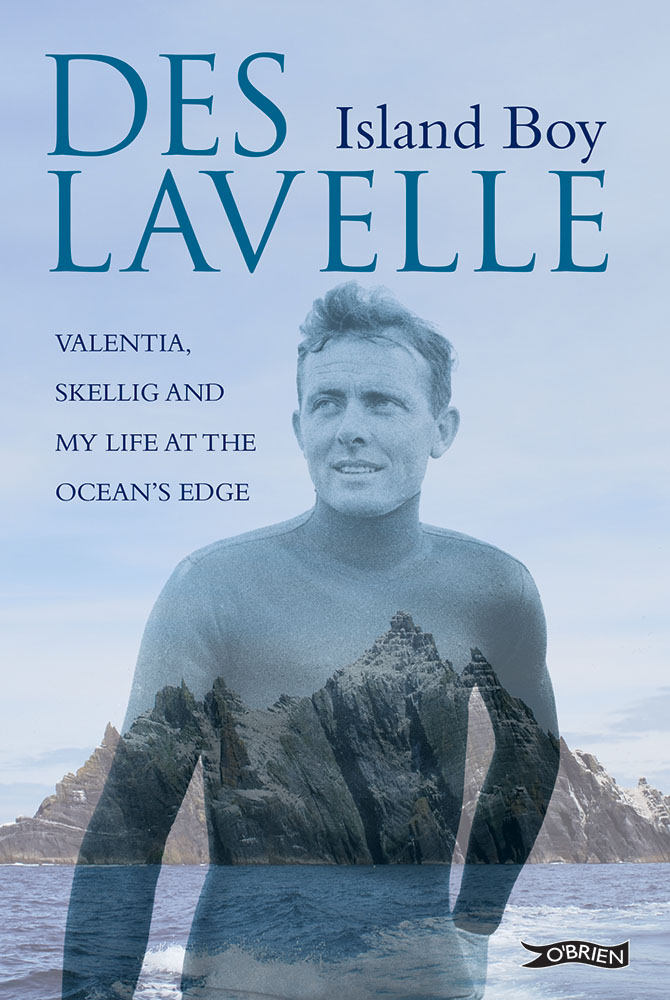

An extract from Island Boy – Valentia, Skellig and My Life at the Ocean’s Edge by Des Lavelle. Published by The O’Brien Press. In bookshops now, priced €19.99