Gaels on film—the big screen adaptation of Catherine Cookson’s Rooney

Like Jacqueline (see Books Ireland May/June 2019), the 1958 film Rooney is based on a Catherine Cookson novel, and like Jacqueline, the action was switched from South Shields to Ireland. It seems that the triumph of John Ford’s The Quiet Man (Books Ireland Jan/Feb 2015) in 1952, prompted a number of British film makers to attempt to emulate its success. As commented on before in this column, however, few attempts are memorable.

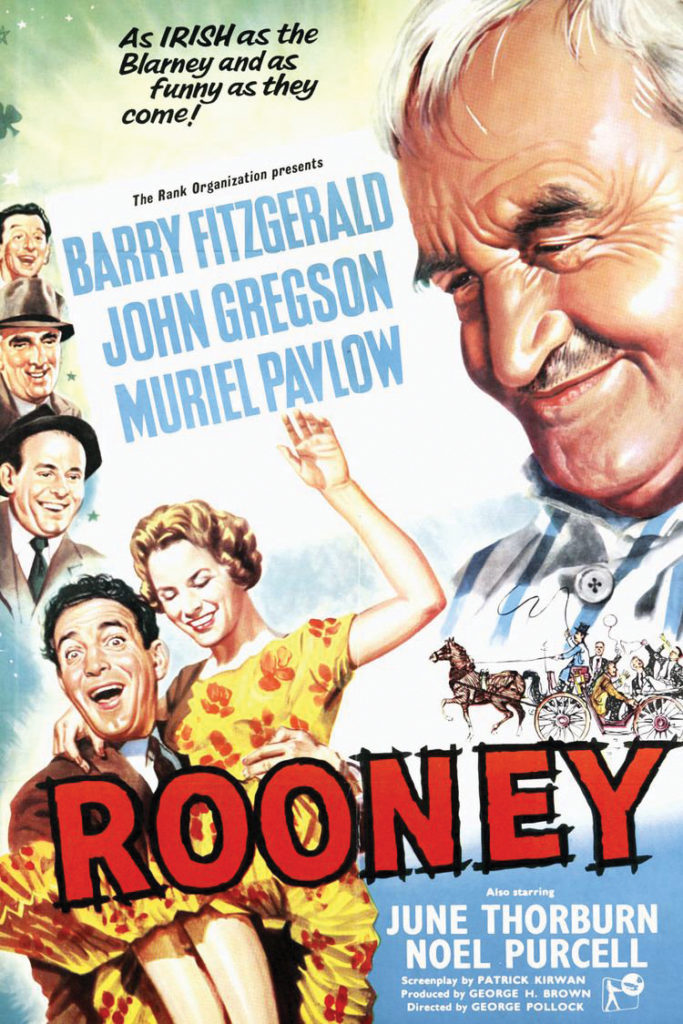

Apart from the setting and most of the cast, Rooney was very much a British film. It was produced by George H. Brown (who also produced Jacqueline) and directed by George Pollock. He is probably better known for bringing Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple to the big screen for the first time in 1961 with Murder She Said, which he followed up with three other Miss Marple adaptations: Murder at the Gallop, Murder Most Foul and Murder Ahoy. Rooney was shot mostly in Pinewood studios, London, although the outdoor scenes were shot in Dublin. Liverpool-born John Gregson plays the title character. Although a likeable actor, Gregson had trouble with his Irish accent. Alongside him, most of the supporting cast features some well-known Irish actors like Barry Fitzgerald, Noel Purcell, Liam Redmond and Marie Kean.

In the original Cookson novel, Rooney Smith, an unmarried 35-year-old dustman in South Shields, is a man who likes the ladies but is determined to remain a bachelor. His job, and his two treasured roomfuls of furniture, are all he needs to be content, but when he moves to new lodgings with Ma Howlett, his life takes an unexpected turn. The film takes some liberties with the plot. The main character is now James Ignatius Rooney, who plays hurling on Sundays and is a Dublin binman during the week. The main plot concerns Rooney’s rise to stardom on the county team but it betrays a lack of understanding of the GAA and the hurling scenes leave a lot to be desired. Indeed, overall, it is very Oirish with its portrayal of stout- and whiskey-drinking and broad humour.

The film is more notable for the behind-the-camera stories. The climax is Rooney playing for Dublin in the All-Ireland final but the teams actually playing are Kilkenny and Waterford (which were in the 1957 final). Gregson was coached in the use of a hurley and sliotar by Gaelic star Dessie ‘Snitchy’ Ferguson but was a hopeless hurler. The scene where Rooney scores a vital point took hours to shoot as Gregson had to make several attempts to get the ball over the crossbar. The Kilkenny and Waterford players agreed to participate in the shooting of the film, some of which took place during the All-Ireland final itself—at one point Gregson slipped onto the field to join the Kilkenny players on their ceremonial parade before the match. And then they had to spend six hours in Croke Park while the director shot the hurling scenes featuring Gregson. Despite all this, it is not the match that provides the drama, but a plot line wherein Maire, the girl Rooney has fallen for, is accused of theft and Rooney rushes from the game to the Garda station to clear her name.

Dublin would appear to have welcomed the British film company with many events laid on in honour of John Gregson and his co-star Muriel Pavlow. The film had a glamorous premiere in Dublin with President Sean T. O’Kelly and government ministers present. Rooney was reasonably well received in Ireland and abroad. Bosley Crowther in The New York Times said that ‘We must say, John Gregson goes at the title role of the happy young bachelor dustman with a lively good nature and comic will’. Writing in the Radio Times, reviewer Tony Sloman gave the film three out of five stars, as he deemed it ‘really quite charming’. Allmovie, the online film guide, concludes that it is ‘stronger on characterisation than plot’ and that ‘the film is at its best when the camera roams around the misty streets of Dublin, and at its worst when it pauses for sentiment’. Most Irish reviewers tended to scoff at the ham-fisted hurling scenes ,while others were appalled at the portrayal of hurling as a rough violent game. Today, as some critics did at the time, the film is usually criticised for its portrayal of Irish stereotypes and two-dimensional characters.

As with many other films made in Ireland in the twentieth century, in some ways Rooney is important as a historical document. The street scenes in Dublin, and particularly the shots of Croke Park, capture a city that has long gone. Many of the buildings shown in the film were soon to fall prey to developers and the bike-friendly roads would become dominated by motor traffic. And, despite its many failings, Rooney does record the social make-up of Dublin at that time, as the refuse collectors, on the bottom of the social scale, empty the bins of the grand houses, some still occupied by ‘relics of auld decency’.

Tony Canavan, Consultant Editor Books Ireland