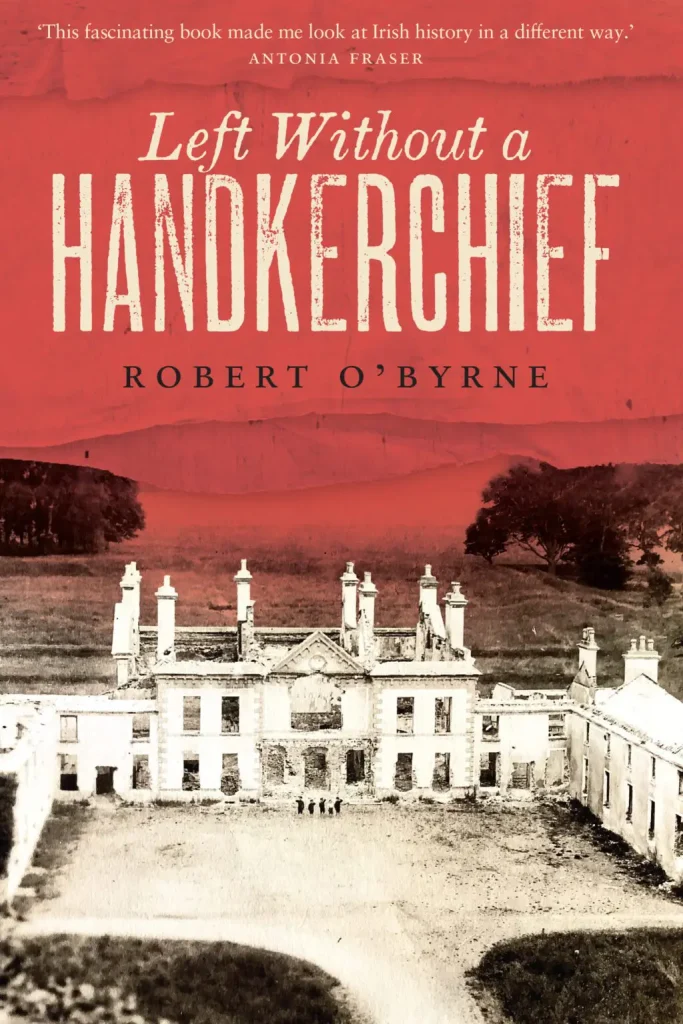

Left Without a Handkerchief|Robert O’Byrne|The Lilliput Press|ISBN: 9781843518181|€18

History of the Big House, in Left Without a Handkerchief (Lilliput Press)

by John Kirkaldy

The ritual was nearly always the same. ‘Typically, a large group of men, most often masked, would arrive in the early hours of the morning at the door of a property demanding entry and, if this was not forthcoming, would break some windows to gain access…the owners would be kept at gun point until the fire had caught hold of the building.’

It has been estimated that nearly 300 large houses were violently attacked in the period 1919-23; about 76 in the War of Independence and 199 in the subsequent Civil War.

Louise Bagwell described in a letter what happened at 2.30pm on 9th. January 1923, ‘for an hour we had to stand and watch the darling house burn.’ Marlfield, County Tipperary had been their family home for some 230 years and they were left with what they stood up in. ‘We hadn’t even a handkerchief.’

Displaced owners

Robert O’Byrne’s book is a study of ten examples: three in County Kerry; two in Kilkenny; and others in Galway, Mayo, Tipperary, Waterford and Westmeath. The emphasis is very much on the displaced owners and is a good complement to the recently published history, Burning the Big House by Terence Dooley.

O’Byrne’s detailed researched account uses not only letters, family histories and contemporary accounts, but also compensation claims to the British and Irish Governments.

The motivation for the attacks, O’Byrne argues, is more complex than is sometimes depicted. Land, landlords and their agents are some of the most emotive topics in Irish history. In 1870, 97% of the country was owned by landlords; yet by 1916, 70% of Irish farmers owned their land, thanks to Wyndham’s Land Purchase Act of 1903.

It would, however, take more than a few decades to remove these deeply held views and not all the problems were solved.

The Big House

The Big House was seen with justification as generally pro Union and later, as Pro Treaty (it is important to note that a majority of the burnings took place during the Civil War).

Liam Lynch, IRA Chief of Staff, issued an order in December 1922 that ‘all Free State supporters are traitors and deserve the latter’s stark fate, therefore their houses must be destroyed at once.’

The collapse of law and order encouraged looting. The burning of the property was often preceded by the stealing of cars, farm implements, wood and produce; windows were often smashed and buildings vandalised.

Anglo-Irish

The house owners were predictably all members of the Anglo-Irish community. They were part of that perennial paradox: being seen as English by the Irish and Irish by the English.

Their background often comprised English public school, study at either the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge or Trinity, Dublin. Many served in the British army; others were MPs, JPs and involved in business. The British Empire often played an important part in their lives.

Typical was the burning of Ardfert, County Kerry, which was set on fire on 3rd. August 1922. The land and houses in the area had been in the Crosbie family (later Talbot-Crosbie) since the late sixteenth century. The money that the family gained as compensation, they put to building houses in Glenageary, Dublin and Howth.

Not all the families involved completely fit into this picture.

The Morris family of Spiddal House, County Galway, for example, were devout Catholics. A few, like Sir John Keane of Cappoquin, County Waterford, were supporters of Home Rule. Lady Desart of Desart Court, County Kilkenny was a committed member of the Gaelic League and was a noted local philanthropist.

The Anglo-Irish have a reputation of inter-marriage and O’Byrne sets a sure course through family trees, scandals, the odd duel and the complexities of inheritance.

A few did not go quietly. When Walter Skrine of Ballyrankin, County Wexford was held at gunpoint in his study in July 1921; he put up a struggle and was warned apologetically by one of the raiders, ‘please steady yourself, Captain, or we will have to shoot you.’ To which came back the reply, ‘I would rather be shot in Ireland than live in England.’

Twilight of the Ascendency

The period 1921-23 was the twilight of the Ascendancy in Ireland. Reprisals and counter reprisals ratcheted up the violence even further. Many of the barracks of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) were out of action; the Big House was sometimes used as the base for Free State forces or as a store for arms.

A few Anglo-Irish, such as the Earl of Mayo, were Senators; his house at Palmerston, County Kildare, was burnt. When he asked if he was to be shot, he was informed, ‘No, my lord, ‘we are not going to shoot you, but we have orders to burn the building.’

Official executions by the Cosgrave Government (figures vary between 77 and 81) meant even more reprisal burnings. Lady Mabel Annesley was a representative voice; every night she would sit in Castlewellan, County Down, ‘in tweed skirt and thick shoes with valuables packed in suitcases ready to throw out of the window.’ The question of the Big House and their perceived handling of land issues may also have been a factor in some cases.

After the burnings

One of the fascinating details of the book is what happened after the burnings. The owners all put in large claims for compensation in the 1920s to a Government that was very strapped for cash.

The claims were reduced but eventually paid on the understanding that the house would be rebuilt or an alternative arrangement could be agreed.

Most were indeed rebuilt and the book traces their subsequent histories. Kilboy, County Tipperary, for example, was at one time owned by Tony Ryan, founder of Ryanair. Bingham Castle, County Mayo, in contrast, was never rebuilt and the land divided by the Land Commission. The Keane family still live at Cappoquin.

O’Byrne rightly claims that: ‘Until now, fiction has provided the only insight into what happened from the perspective of an Irish country house.’ He lists Elizabeth Bowen, Molly Keane and J.G. Farrell. He writes well and has done extensive research and, in so doing, has added considerably to an understanding of an important aspect of Irish history.

John Kirkaldy has a PhD in Irish History, worked for many years with the Open University and has been reviewing for Books Ireland since 1980. He has contributed to three Irish history anthologies, a school textbook, and has been involved in a number of Open University History documentary series. Aged 70, four years ago, he went round the world on a much delayed gap year described in his book, I’ve Got a Metal Knee: a 70-Year Old’s Gap Year.