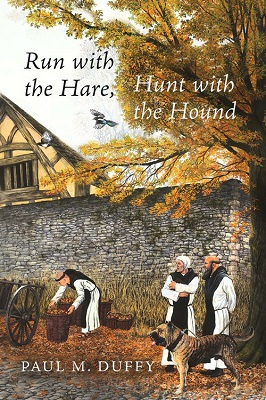

Run with the Hare, Hunt with the Hound|Paul Duffy|Cynren Press|€30

An intimacy with the past and an archaeologist’s imagination

Dr. Sharon Greene on Paul Duffy’s debut novel, Run with the Hare, Hunt with the Hound.

by Dr. Sharon Greene

The Anglo-Norman invasion was not simply a moment in time. It was a process made up of several events, with many actors.

The society it arrived to was not static and unchanging. Some aspects of the invasion were all too familiar in a political landscape accustomed to cross-border incursions, sometimes on a provincial scale. This is, indeed, what brought the Anglo-Normans in the first place.

Their arrival is nonetheless one of the most important moments in the history of the island of Ireland. Still, the actual invasion can be overlooked in a way. It was more than just the event that brought us the subsequent eight hundred years of rule from across the Irish Sea.

Have we ever asked ourselves—what was it really like for the people scattered through the Irish countryside, living in a world where news came slowly via travellers who might only bring rumours?

Bringing the 12th Century to life

In his first novel, Paul Duffy has brought these very people, their communities and even the Irish landscape of the end of the 12th century to life. He could hardly have been more ambitious in his goal to portray the three worlds of the rural Gaelic Irish, the (by then) Hiberno-Norse townscape of Dublin, and the emerging ‘Engleis’ overlay that was just under construction.

With the exception of those living within and in the immediate hinterland of the towns founded by the Norse in the previous couple of centuries, the majority of Irish were living in rural settlements, within tuatha and within an accepted social structure.

However, even this social structure, familiar to those who study early medieval Ireland, is shown to have its problems and challenges.

The institution of slavery is challenged by the church, and the law of Adomnán, promulgated at the end of the 7th century to protect women, children and other non-combatants in times of war, still needs to be invoked.

Identity

The main character, Alberic, was born a slave to parents taken from England and sold to an Irish lord. He does not remember his mother but still lives and works alongside his father, speaking the language of a homeland he has never seen, as well as the language of his masters.

This liminal identity is how he came to be brought to the court in Dublin, gaining access to those working to take over the land on behalf of the Engleis king as well as those who worked for them and around them in the busy city and port.

Throughout, identity is a key theme, as Alberic tries to find his place in this complex world.

Historical records and commentary focus too often on the aristocratic, the military and the male. In the past changes in the archaeological record have focused on the architecture of occupation and even studies of agricultural, industrial and religious changes, more often the realm of the common people, don’t give us a clear picture of those people.

As the story brings Alberic into contact with characters of differing statuses and origins, we hear different voices and see different relationships with the bigger events.

The lords with familiar names of de Lacey, Tyrell, etc are made individual. Women are present in almost every scene – be it as victims of assault, servants and slaves, or wives involved in craft, childcare or their own political machinations. In short, their status may not equal that of men, but their lives are no less bound with all that is happening around them.

Intimacy with the past

Duffy’s writing is almost poetic but there is a realism to it that draws the reader into each scene and activity. His vast experience as an archaeologist allows him to describe objects, activities and features of the landscape with a confidence born of his own familiarity with what he is envisaging.

Archaeologists, while excavating, planning and interpreting the sometimes ephemeral remains of everyday activities, are privileged to receive a kind of intimacy with the past that is difficult to otherwise obtain.

Excavating the fill of a large, mucky ditch on a drizzly day cannot fail to bring to mind those who dug it out in the first place.

This archaeological imagination has, I believe, had a large part in what makes this novel special, alongside Duffy’s historical knowledge and skill as a storyteller.

This, along with the wonderfully drawn characters, all comes together to create a fantastic story that allows the reader to engage with a key period of the Irish past, and maybe even to appreciate it in a new way.

Dr. Sharon Greene is Editor of Archaeology Ireland.