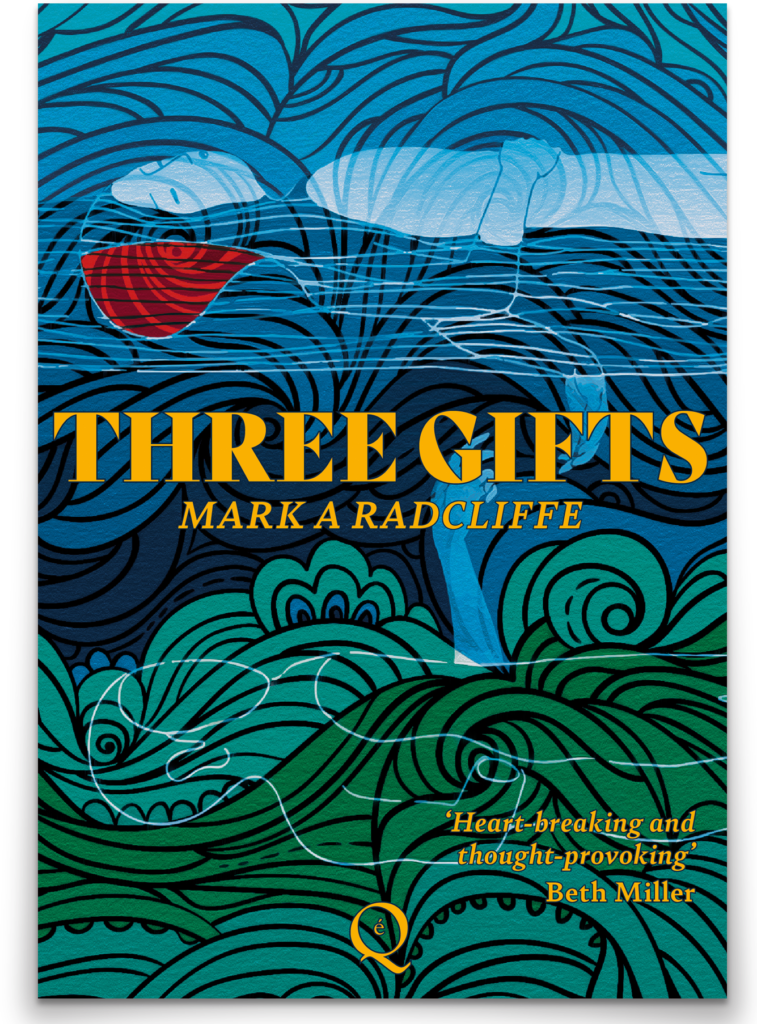

Three Gifts|Mark A. Radcliffe|époque press|£9.99

A Faustian pact with a difference—Eoghan Smith reviews Three Gifts, by Mark A. Radcliffe (époque press)

by Eoghan Smith

Three Gifts is the first novel in ten years by English author Mark A. Radcliffe, whose other books include Gabriel’s Angel (2010) and Stranger than Kindness (2013). It follows the story of Francis Broad who, after an encounter on a beach as a boy with a mysterious man referred only to as ‘the swimmer’, trades in years of his own life to extend that of his terminally-ill mother, Rose.

The premise then, is a version of the Faustian pact but with some key differences. In a Faust narrative, the protagonist typically trades their soul with the devil for unlimited wealth, knowledge or power.

In Three Gifts, Francis offers up a portion of his life in an act of supreme selflessness, while ‘the swimmer’ is less a devil than a species of guardian angel. At least, that is how ‘the swimmer’ appears in the story, who is a personification of his own instinctive capacity for self-sacrifice, or from another angle, a manifestation of Francis’ earnest desire to preserve the life of a loved one.

The premise then, is a version of the Faustian pact but with some key differences

Perhaps ‘the swimmer’ can be read also as an imaginary guiding paternal figure, after Francis’ own father first abandons his wife and young son and then dies a few short years later. After all, it is ‘the swimmer’ who teaches Francis how to swim in the sea (providing a metaphor for how we are immersed in and must learn to navigate, but never completely control, turbulent forces of life) and periodically appears at times of crisis.

Changing attitudes

Francis’ father’s demise and the fear of his mother’s death shapes his formative years. She is a kindly and slightly tragic figure, with whom he has a special and abiding bond. She also provides a moral contrast to her handsome, chauvinistic husband, with his yellowy 1970s nicotine- and beer-breath glamour.

There are also quiet and subtle observations in the novel about the changing attitudes of English society over the last fifty years or so.

In its own understated way, Three Gifts charts the transition towards what might be termed a more tolerant society. The death of Francis’ father, as traumatic as it is, marks the metaphorical paving of the way for a new social order, represented by Francis and his relationships with other people.

Love and sacrifice

Three Gifts is a book about unobtrusive people, about finding and nourishing love, about the sacrifices that people make for each other in sometimes, but not always, difficult circumstances.

It is also a book about finding friendship. Rose welcomes Francis’ college friend Ben, a gay man, who has been ostracized by his own father and whom she welcomes as if he were her son. Francis’ other friend, Joy, somewhat less fully sketched, is nonetheless good humoured and friendly, though we do not get much sense of her own life. Like Francis, who is a keen and able gardener, Joy and Ben have small touches of the nurturing creatives about them: Ben is a fine wood craftsman while Joy teaches Francis’ daughter how to play the guitar.

It is also a book about finding friendship

In spite of the extraordinary premise – a deal made with a stranger to shorten one’s life to save another’s – as a person Francis remains unremarkable, though perhaps ordinary is a more appropriate adjective. As a hero, he achieves virtually nothing particular of note in his life: his college career results in a mid-level Humanities degree that enables him to become a teacher for a while and then a gardener.

His wife, Victoria, also a teacher, struggles a little with motherhood, but not too much, and while she and Francis experience some dips in their relationship, generally they get along and support one another. Their daughter Rae is a budding musician—yet one suspects her music is passably head-nodding but not particularly original.

Ordinary lives

This ordinariness of the lives depicted in Three Gifts is striking; for large portions of it, Francis acts as if he has learned nothing particularly extraordinary about himself. In some respects, he is a man entirely without a developed psychology. For the book does provoke, if not dwell on, the question: what must it be like to know the precise date on which you will die?

For most people, this would be an unbearable state of affairs, driving some of them into madness, perhaps even killing themselves as an act of rebellion. An entire tradition of existentially-inflected literature centres on such dread of death, the absence of God, the meaningless of life and the terrible boredom that we are afflicted with while we wait for the final hour.

For most people, this would be an unbearable state of affairs, driving some of them into madness, perhaps even killing themselves as an act of rebellion

No doubt that in the hands of some writers, we might either be invited to scorn Francis’ minor ambitions or admire his stoic self-sacrifice. But knowing the date of Francis’s ever-arriving end does not spark for him some Dostoevskian speculation about the punishments of God or the arbitrariness of the universe; he does not enter into Nietzschean delirium by embracing his life as the only life he has and will ever have.

Radcliffe stays far away from such philosophical territory; instead, Francis sets about building the most ordinary life for himself imaginable. He emerges out of relative childhood poverty to adult middle class stability, he swims, he gardens, he moves to Brighton. He keeps his aspirations modest and worries in his own way about other people.

It is in keeping with his character that Francis obtains a middling Humanities degree; he is not the kind of elevated thinker who drives himself demented about his fate.

Gratitude

Radcliffe wants us to think about other things: about the gift that is life, about what it means to live selflessly, about how to be loyal, responsible, faithful and love unconditionally. And that, ultimately, goodness is enacted in small but meaningful ways and that we should be grateful for what we have.

It is a highly enjoyable, tender novel

In this respect, Three Gifts is edifying. In the final pages, Francis begins to feel something of the terror that accompanies the awareness of death but the tone is more light than dark, as it is throughout the entire book, and indeed, Radcliffe is a fine comic writer.

It is a highly enjoyable, tender novel, and it is genuinely refreshing to read a book where the principle character is not tortured by his circumstances and surroundings or rages against the injustice of a cold, silent universe – there are many such books, such characters – but is instead simply prepared to surrender some of his own life for those around him.

Francis Broad’s gentle, manly heroism lies in his generosity, modesty and decency, and perhaps these are the not worst qualities to have.

Eoghan Smith is the author of The Failing Heart (Dedalus 2018). His second novel, A Provincial Death is out now with Dedalus.