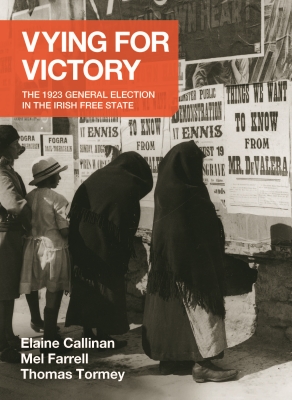

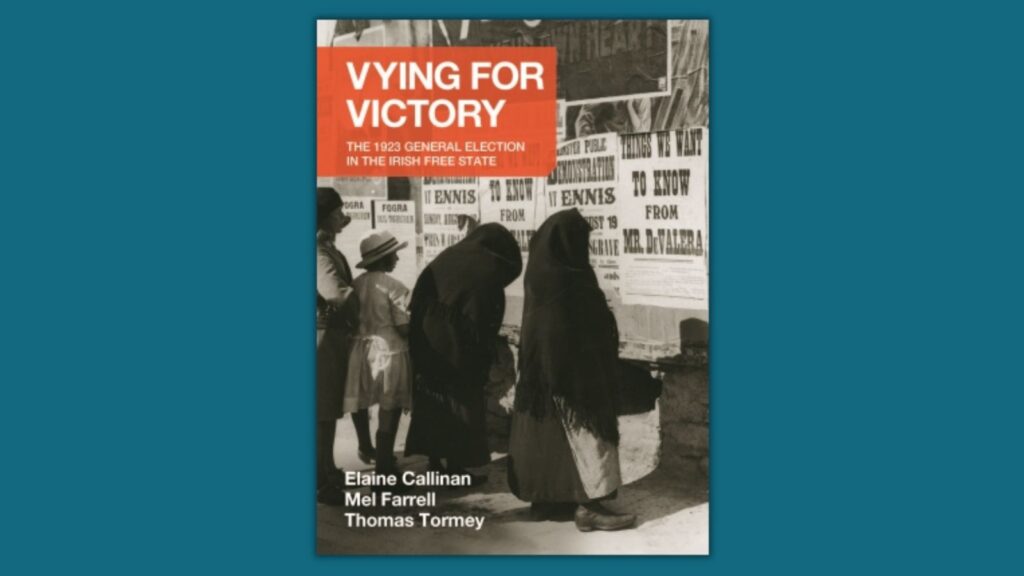

Vying for Victory: The 1923 General Election in the Irish Free State|Elaine Callinan, Mel Farrell, Thomas Tormey (eds)|UCD Press

Vying for Victory—Laying the foundations of the Irish electoral system

by John Kirkaldy

This is the kind of book that gives academic anthologies a good name. Unlike some of the species: it has a clear focus; a very worthwhile variety of articles that complement each other; and it is mercifully free of contributors straining for effect through obscure concepts and jargon-laced vocabulary.

The 1923 Free State General Election marks the beginning of modern Irish democracy. It was held on 27th August, only a few months after the ending of the Civil War in May. This was at the end of the most turbulent decade in Irish politics—the Home Rule crisis, the impact of World War One, the Easter Rising of 1916, Partition and its narrow acceptance by Dáil Éireann in January 1922.

A record of 376 candidates stood and every seat was disputed under a system of PR, except Dublin University. A major change just before the election was the introduction of universal franchise for everybody over 21. Women were able to vote for the first time and on equal terms with men (in Britain, they had to wait till 1928).

Women were able to vote for the first time and on equal terms with men (in Britain, they had to wait till 1928)

The most important aspect of the election was that it took place successfully after a bitter Civil War. Estimates of the death toll are between six and seven hundred. Between November 1922 and May 1923, 81 imprisoned republicans were executed. In December 1922, four republicans were executed in retaliation for the murder of Government TD, Seán Hales. 11,316 republicans, including 250 women, were imprisoned during this period. Despite this, the election results were generally accepted, if not welcomed in all quarters.

Safety First policy

Mel Farrell sees the success of William T. Cosgrave and the Cumann na nGaedheal Party as being based on the slogan Safety First. He urged voters on the eve of the poll: “Strengthen those who have brought peace to the nation, consolidate your gains by your votes, mark your preferences in the order of ability to maintain sacred life, liberty and security.” The passing of a Land Act was used to gain support for the completion of land purchase.

The Party emphasised its nationalist credentials but was also keen to recruit other supporters. Farrell comments: “These voters, often ex-adherents of the Home Rule Party and southern unionism, desired stability, the restoration of law and order and balanced budgets.” It won 39.0% of the vote and gained 63 seats, making it the largest party but without an overall majority. The abstention of Sinn Féin gave Cosgrave a comfortable majority in the Dáil.

Priests were often active at local levels—chairing meetings, nominating, seconding and endorsing candidates

There were also other powerful forces supporting the Safety First policy. Daithi Ó Corráin demonstrates that the Roman Catholic Church was very strongly behind the Government. At all levels, the clergy echoed Archbishop Thomas Gilmartin’s words to voters: “Return them to power with sufficient strength to complete their work.”

Priests were often active at local levels—chairing meetings, nominating, seconding and endorsing candidates. There were a few priests, such as Reverent Patrick Keran, who nominated Éamon de Valera, who gave support to Sinn Féin. At the end of the election in a letter to Bishop Michael Fogarty, Cosgrave commented that electoral success had come about from support of people “in high and important positions throughout the country.”

Another source for stability were smaller parties, which had political agendas largely outside the debate over nationalism. Jason Knirck sees the Farmers’ and Labour Parties as ‘searching for the normal.’ The Farmers’ Party gained 15 seats and 12.1% of the vote; while Labour won 14 seats and 10.6% of the poll. (The Businessmen’s Party and the Cork Progressive Association both gained two seats each.) Their demands were underlined by the parlous state of the Irish economy.

Appraisal of de Valera

In a challenging appraisal of de Valera and his role in the Election, David McCullagh sees it as a crucial time for him. “It did not just decide his immediate political future—it decided whether he had a political future.” By the end of 1921, “his political power had been ebbing away” over the negotiations in London over the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the subsequent vote in the Dáil. He was in something of a no man’s land between the militarists and the more moderate abstentionists. His prestige enabled the relaunching of a revitalised Sinn Féin Party to fight the Election.

It did not just decide his immediate political future—it decided whether he had a political future

The Party gained 44 seats and 27.4% of the poll and de Valera was returned with a massive personal vote in Clare. On 12th August, he was arrested while speaking in Ennis. In May 1926, he founded the Fianna Fail Party and in August 1927, he broke with the policy of abstention and entered the Dáil. It has with Fine Gael been the central fulcrum of Irish politics until recently.

Implications for Irish society

An additional strength of the book is that it sees the election, not just in terms of immediate results, but also in its general implications for Irish society. Elaine Callinan provides a very detailed appraisal of the votes and looks also at the Parties’ political propaganda techniques. Owen O’Shea investigated local newspaper coverage in Kerry during the Election and found that it was overwhelmingly in favour of Cumann na nGaedheal.

Sinn Féin had four women TDs but due to their Party’s policy, they did not take their seats

Claire McGing views the role of women in the election as a very limited one but an important step for the future. Only one woman, Margaret Collins O’Driscoll, Michael Collins’ elder sister, sat in the Dáil. Sinn Féin had four women TDs but due to their Party’s policy, they did not take their seats. One, Caitlin Brugha, was the widow of Cathal Brugha, who had been killed by Free State troops. More immediately important was the growing number of women activists that were involved in the election at grass roots level.

Regina Donlon argues that the election caused friction within the Irish American community

Regina Donlon argues that the election caused friction within the Irish American community. The newly formed American Association for the Recognition of the Irish Republic (AARIR) was unable to cope with the demands of events in Ireland with the local needs of the Irish American community at home. Many Irish Americans’ knowledge of Ireland was often based on dimming memories or hearsay. There was also the issue of how much direction should come from Irish politicians. In 1921, membership stood at 700,000, by 1925, it was only 13,870.

Watershed

Any society that goes through a civil war will have scars and Ireland has been no exception. The Election of 1921 was, however, an important watershed; it established a political system that has functioned ever since. Gearóid Barry argues a convincing case that Ireland emerged stronger than many other countries trying to cope with a post World War One world.

He instances Mussolini’s Italy, the Russian Revolution and its aftermath, the ending of the Austrian-Hungarian empire, the French occupation of the Ruhr, Hitler’s Munich Beer Putsch and Turkey’s invasion of Smyrna. It has taken two, possibly three, generations for Spain to overcome the divisions of its Civil War.

He ends with a convincing conclusion: “Flawed as the emergent socially conservative society consensus in the Irish Free State was, the willingness, even in 1923, to share the electoral space surely helped to make the more benign Irish political outcome—of an eventual peaceful transfer of power later in 1932 between Ireland’s civil war victors and vanquished—more likely.”

This book is recommended without reservation.

John Kirkaldy has a PhD in Irish History, worked for many years with the Open University and has been reviewing for Books Ireland since 1980. He has contributed to three Irish history anthologies, a school textbook, and has been involved in a number of Open University History documentary series. Aged 70, five years ago, he went round the world on a much delayed gap year described in his book, I’ve Got a Metal Knee: a 70-Year Old’s Gap Year.