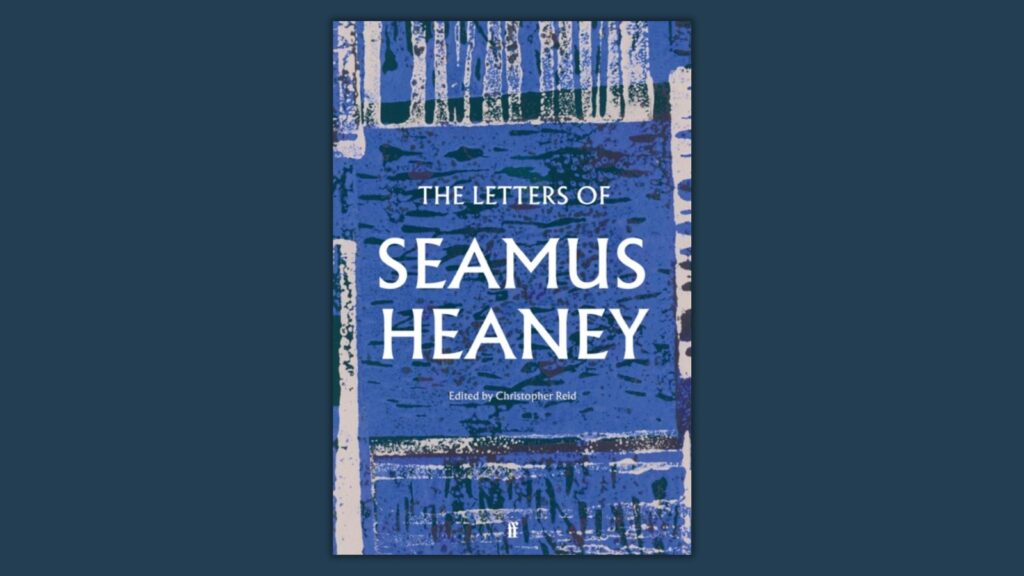

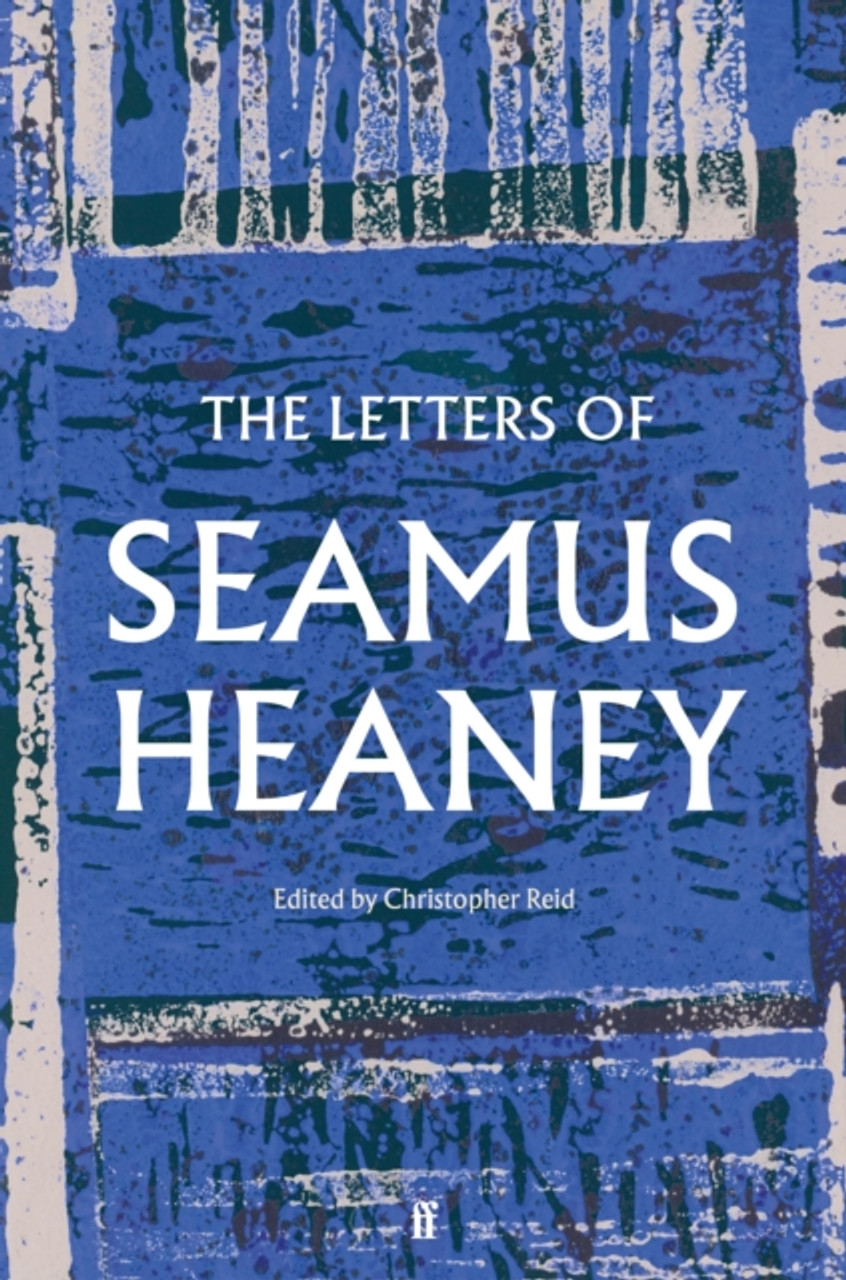

The Letters of Seamus Heaney|Ed. Christopher Reid|Faber

Uncanny gleams, the unexpected, and a steadying, compulsively readable voice

by Adam Hanna

A premonitory rumbling of drums can be heard near the outset of this compendious selection of Seamus Heaney’s letters. By chance, on the day in June 1965 that Heaney wrote to Faber and Faber to accept their offer to publish his first collection, Death of a Naturalist, he also attended the opening of Yeats’s tower. In the light of the Nobel prize that came to Heaney thirty years later, this encounter with the older Nobel-winner’s symbol of achieved labour seems like an early omen.

One of the pleasures of these letters is the way they allow readers to see uncanny gleams like these. The value of this book of letters might be understood with recourse to an idea of Yeats’s, too, one that Heaney quoted in one of his own essays: “Above all it is necessary that the lyric poet’s life be known that we should understand that his poetry is no rootless flower but the speech of a man.” This volume is the most valuable set of contextual writings on Heaney since Stepping Stones: Interviews with Seamus Heaney, was published in 2008.

This volume is the most valuable set of contextual writings on Heaney since Stepping Stones: Interviews with Seamus Heaney, was published in 2008

The Letters of Seamus Heaney is the epic of the poet’s elevation to the Nobel Prize for Literature, and a record of his heroic attempts to mark out and maintain the necessary space to keep writing in spite of his own vast success. The letters are well-selected and signposted: in his role as an editor, Christopher Reid is (to fall into the kinds of alliteration to which Heaney was endearingly prone in his letters from the time he translated Beowulf) tactful and trustworthy, surefooted and scrupulous.

The voice that emerges from Heaney’s decades of letter-writing is steadying and compulsively readable. As a correspondent he is adaptable and self-possessed, wry and insightful. It’s easy to picture him writing with a half-smile: he describes himself as communicating ‘bashlessly’ when he feels he is showing off. He imagines reviews for an imagined volume of poetry: ‘‘’Zap!’ (Clive James). ‘Hm’m’ (R. S. Thomas).’” His sole words on a postcard to a friend, where his own head is on the stamp, are “Ah, well…”.

The voice that emerges from Heaney’s decades of letter-writing is steadying and compulsively readable

There are other humanising moments, as when he accidentally throws away a vast cheque meant for a charity, and must go cap-in-hand to the Duchess of Abercorn for a replacement. It is moving to see him consoling Michael Longley with a breezy ‘Noli timere, frater’ in 1969, decades before those words became famous for being his last.

The key facts of Heaney’s life—from thatched cottage to Belfast to Berkeley, thence to the Republic and Nobel success—are so well known that it is perhaps worth dwelling on what is surprising in this selection. There is an unexpected Joycean implacability in his refusal to take communion at his mother’s funeral mass, for example. His citing of Louis MacNeice as an exemplar in the tricky business of writing poetry in the face of atrocity came as a surprise to me, too: “I think MacNeice’s ‘Sunlight on the Garden’ is as much an ave to Auschwitz as it is a vale to a love”, he writes. And then there is the brief 2003 media commotion when he praises Eminem for his ‘verbal energy’. There are unexpected darker threads, too. Seamus Deane is probably the writer most associated with the Field Day controversy, which was prompted by the scandalous neglect of women writers in the group’s monumental anthology of Irish writing. These letters show how compromised and implicated Heaney felt at the time.

There are unexpected darker threads, too

The stratospheric nature of Heaney’s career comes into focus in a letter he writes from Concorde in 1990. This habit of letter-writing on airplanes was forced on him from a life spent always on the move, perpetually ‘toing and froing’, as he puts it. From the earliest letters he is a master of the charming apology for lateness. We see him constantly taking on too much, an unbreakable habit that stays with him until the end. However, around the time of his supersonic journey, the reader gets the sense of a golden age, when Heaney was on top of the world, with a glowing reputation and the energy and zest to enjoy it. That flight, with its caviar and crayfish, is towards a party with guests that include Archbishop Desmond Tutu. “What’s happened?” he writes from high above the earth’s curve.

From the earliest letters he is a master of the charming apology for lateness

The sense of obligation, and Heaney’s unending consciousness of there being more work to do, take their toll. Years later, he frets mildly at an invitation from the White House for Saint Patrick’s Day. It is painful to read of the weight of requests and the laboriously-fulfilled duties, and the expense of time and energy these things took as age and illness encroached. The lines that came to me as I read the many letters with these themes were Louis MacNeice’s: “The strong man pained to find his red blood cools”. It is also distressing to see Heaney’s sense of panicked exposure, and the second thoughts, that attended the publication of the compendious volume of interviews with Dennis O’Driscoll, Stepping Stones. “Dennis is a civil servant of compulsive, exhaustive disposition”, he ruefully notes in a late letter.

What comes across most strongly and impressively from these letters is the ethic of perseverance that powered Heaney’s scarcely credible output of work: books, readings, collaborations, and more. “Keep going”, he often signs off letters to friends. He writes to a painter friend of “the medieval anchorite, Macoige of Lismore, who said – in Irish or Latin, I assume – that the best attribute of character was ‘steadiness, for it is best when a man has set his hand to tasks, to persevere. I have never heard fault found with that.'”

On a few occasions he deploys this quotation: “This is it, this is the thing, this is the thing you’re up against.” Its source is unclear – he calls it ‘the Dublin triad’ in one letter, and ‘Sean Mac Réamoinn [an Irish journalist] philosophy’ in another. Still, if its source is ambiguous, the mindset it reveals is not.