In our latest Poet on Poet, Julie Morrissy talks with Milena Williamson about bringing up a body of imaginative work in her debut collection Into the Night that Flies so Fast

Milena Williamson‘s debut collection Into the Night that Flies so Fast (Dedalus Press) is about the life and death of Bridget Cleary, who was burned to death by her family on suspicion of being a fairy changeling.

This interview took place in Belfast after Morrissy and Williamson met for the first time the previous evening. It started at Established Coffee and continued during a walk and a short car journey.

JULIE MORRISSY: Maybe it would be good if you start by telling me about Bridget Cleary.

MILENA WILLIAMSON: Where to begin with Bridget really. She was born in Ballyvadlea, near Clonmel, Co. Tipperary. There’s some debate about when she was born, around the question of her birth year versus when she was baptised in the church, an uncertainty which is noted by Joan Hoff and Marian Yates in The Cooper’s Wife is Missing. So, 1869? She died in 1895. She was very unusual. Bridget was educated, she went to school. She was the youngest child, the only girl in her family. She was literate. She earned money through her hens. She trained to be a seamstress in Clonmel. She was very independent, and was described as “a bit queer”, according to the Cork Examiner after she was murdered, meaning she was odd. She was married but didn’t have any kids, which was probably seen as suspicious. Then she got sick for ten days, which led to all these strange events happening.

JM: What kind of sickness?

MW: Pneumonia is most likely. Tuberculosis is also possible. In the documentary Fairy Wife: The Burning of Bridget Cleary, someone living locally suggests that she might have had a miscarriage. But I think Angela Bourke lands on pneumonia or TB in her book The Burning of Bridget Cleary. Bridget’s mother died before she did, and she probably helped take care of her at the end of her life. She had three brothers who I don’t mention at all and who are totally absent in this story.

JM: Are they absent in all the stories?

MW: Yeah, they’re absent. Maybe they lived in another town, or they went to America, or they had died. It’s Bridget’s cousins who are in the Clearys’ house. Bridget’s father lived with her and her husband Michael. She was in the caretaker role, and then what happens when the caretaker gets sick?

JM: And how did you start writing about Bridget?

MW: I’m pretty sure it was the poem “Manteo” in Drawing Ballerinas by Medbh McGuckian. In a very un-McGuckian-like move, Bourke’s book is footnoted in this poem and I found that fascinating that McGuckian’s book ends with a footnote, with a reference. It immediately made me want to escape into this footnote or this source, so I think that was where I encountered Bridget.

JM: But you don’t use footnotes? MW: No, I don’t.

JM: Did you think about it?

MW: In terms of references or in terms of form? Because I have done footnote-form poems in another project…

JM: I guess, both. Have you read that book The Body: An Essay by Jenny Boully? It’s in a footnoted form—it’s a poetry book but the body of the page is blank and it’s only footnotes…I think what’s interesting about having this conversation now and about your book coming out this year is there has been this wave of archival work because of the Decade of Centenaries. I’ve been talking with a lot of poets through the Poetry As Commemoration project and through my work at the National Library of Ireland about their practices in entering these archival sources. I’m curious about how you are thinking about citing the historical sources or references and how visible you wanted that to be?

MW: The poems never existed in a form with footnotes. From the beginning of the project I knew there would be a lengthy notes section. I think I could have made it lengthier.

JM: I loved the notes section!

MW: There is one poem called “Some Natural Notes About Her Body” and it occurred to me that I had not actually clarified in the notes section that this poem draws from the joint statement from the physicians who examined Bridget Cleary’s body. Sometimes it’s hard for me to even keep track of which poems are from which specific texts. I say my primary source is Angela Bourke’s The Burning of Bridget Cleary, which is the go-to text. Bourke does an excellent job as a historian and as an archivist. She makes a poet’s job easy—you know, she opens the door.

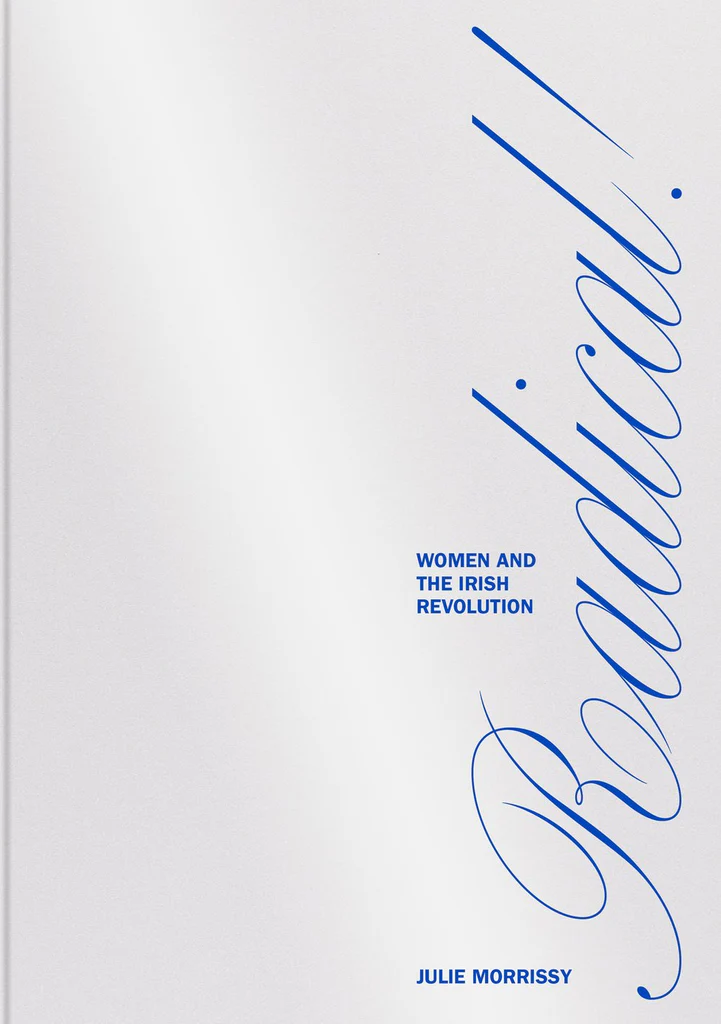

JM: I had this tension with my book Radical! Women and the Irish Revolution too, where I rely heavily on primary sources from the National Library and on scholars who write about the revolutionary women, but what we are doing as poets is a different construction. It’s a poem. We are not historians.

MW: That’s very much how I felt. I am not a historian. I’m not an archivist by training. I’m an archivist by passion, I guess. I didn’t know how much research there was on Bridget Cleary. I found a poem that led me to Bourke’s book, and I thought there was enough that I could sink my teeth into. It is always this question of: there needs to be something there, especially for a poet, to get started and do some creative imagining work, but then what happens if what is there is quickly disappearing? Like the inscription on the gravestone is fading away, or the stones that mark Bridget’s grave that are not inscribed, so you would have to have a certain body of knowledge to begin that creative work. And every poet is going to be different in terms of how much they need to get started. I’m really glad Bourke’s work is there, because I don’t think I could have done my work in any way, shape or form without her book.

JM: I think we worked in a similar way in that we had those sources from historians but we also did “creative fieldwork” by going to those places and having our own experiences and connections.

MW: Yeah, and it’s so interesting to talk to people about the words they use—like when you say “fieldwork”. In my head I was thinking of it as a “research road trip”, even the language that we use—you say this is “creative fieldwork”, and then I think that is what I do…In another interview, I was asked if these are persona poems or monologues…and in my own head I have a tendency to make up language. I just thought of them as “voice poems”, and I’m happy for them to be called “persona poems” or “monologue”…I’m happy with all of those terms, but it’s strange to me the terms that I landed on…research trip versus fieldwork, voice poems versus monologue, what all those things mean, you know.

JM: And, of course, there is a really long history of documentary poetry involving road trips. For me, the cornerstone would be Muriel Rukeyser, but also CD Wright’s relationship with the photographer Deborah Luster. Those things have been part of the way I imagine my practice for a really long time. There’s a poetic tradition here of taking yourself to the site to investigate.

MW: Yeah…I took this trip in 2021. It was coming out of Covid. It was the first time I went back across the border after the travel restrictions, though it was a much firmer restriction where you were…but the first time I went to Dublin was to go to the National Archives of Ireland, and the first big trip was to finally take this creative fieldwork trip. It was going out into the world after a time of extreme locality…Even going to the National Archives, that part was delayed because of Covid. On my first trips to the archives, everything was pre-scheduled and you could only go during specific hours…I’ve since been to the archives not during Covid, and still the number of rules! You go to this window and you need this slip of paper and my computer was plugged in but blocking a pathway and the WIFI didn’t work. The archive was strange and surreal, and it was compounded by Covid and not leaving the house or crossing the border.

JM: I had a conversation with Bebe Ashley and Chiamaka Enyi-Amadi about their poems for Poetry As Commemoration, and I was asking them about the archival work and thinking of the poems as “pressure poems”, partly because for them it was a specific commission, so there is already a pressure of responding to something from the outside, but then also the material conditions of the archive being quite constraining. I mean for me, in some ways, it is the opposite of what I thought I might need to make creative work.

MW: Oh, totally! It leads me to think about poetic form which can be so generative in poetry, but the constraints of space, like the archive, can be overwhelming for a poet. The number of anxieties it can generate… those social rules—where can I put my stuff? Who do I talk to?…Have you read Arlette Farge’s The Allure of the Archives? She has a great essay on archives and people doing weird things and trying to get the right seats. I wrote down one of her quotes: “There is nothing like the judicial archives, which are the rough traces of lives that never asked to be told in the way that they were, but were one day obliged to do so when confronted with the harsh reality of the police and repression… People spoke of things that would have remained unsaid if a destabilising social event had not occurred…Their words reveal things that ordinarily went unspoken”. In my last book event I was talking about reading the oral testimony given at court, at the trial after Bridget Cleary’s murder, and the oral nature of these documents is closer to the oral nature of poetry. It makes sense that poetry as a form could respond to these orally given statements.

JM: I think that connection between law and poetry and the performance of law comes through strongly in your collection. When I read your notes section that was one of the notes I made, thinking about poets like Maggie Nelson and M. NourbeSe Philip—the kind of work that has been informing Irish poetry in the last decade…I would love to talk about the form of the book and the play-form in particular because I was so fascinated as soon as I opened it. How did you decide on that?

MW: That decision was really organic. I actually went to my records recently and even in 2018, in the earliest version of what this book was, even that version was a three-act play.

JM: Is that because you were thinking of the poems in terms of voice, or persona, or character or however you want to call it? Have you written plays before?

MW: Only as a young child in school. So, no, not since school days. But at Queen’s [University Belfast] in Introduction to Creative Writing you study plays, and I was the Teaching Assistant for this course in 2021, so I got to step into that world through teaching, not through my own practice. The play thing is interesting because maybe people think it was a whole plan or idea, but the structural elements of this were always there from the time I found the quotes for the epigraphs of my book. For me, that sets up the way that performance and theatre is so organic to the Bridget Cleary story. Both epigraphs are from the judge at the trial of Bridget’s implicated family members and community members. Justice William O’Brien says “A young woman has met her death under circumstances which remind us of the lines: ‘Pleading like angels, trumpet- tongued,/ Against the deep damnation of her taking off’”. And then he follows that quote, in which he is evoking Shakespeare, with “I will not allow a question as to where fairies are supposed to be. They may be supposed to be in this courthouse. We are not here acting a play, but to inquire into matters of fact”.

JM: It is such an interesting set up…

MW: In the first quote, it’s Macbeth talking about Duncan, deciding whether he is going to murder him, almost in a moment of wavering, and the judge reaches for Shakespeare and changes the pronoun to refer to Bridget Cleary. It is a completely radical thing to do! And then somebody is asking a question, a solicitor from Dublin in fact, and he questions Johanna Burke who is in the witness chair about fairy-belief. The judge says he doesn’t want to go there and he states that “we are not here acting a play”. He is delineating play and reality, and fiction versus fact, and he is putting fairies in this world of plays with fairies and witches and Macbeth. He alludes to the fictional world by quoting Macbeth but then he refuses the question about fairies because it’s too much like theatre.

JM: I think maybe I had a slightly different interpretation. Part of me wonders about his resistance to the question about the fairies, that rather than a rejection of folklore and literal fairytales, it also could be reflective of a real anxiety around superstition.

MW: A kind of embedded belief!

JM: Yes! Where it’s partly because legally it is not the right forum, but also maybe those superstitions were and are so strongly held. I mean, we still have roads that go around fairy trees.

MW: The fear of making the unsaid said?

JM: Yeah—and we are not going to debate that in a legal context because the belief still has a stronghold.

MW: Hearing you say that, I think you can read it both ways. In fact, according to Bourke, Justice O’Brien was “one of only seven Catholic judges on the Irish bench.” So maybe he did have that superstition about changelings. Maybe in my mind, the judge became such a figure of authority that I didn’t imagine him as being so much embedded in the culture of folklore and fairies, but his words can be interpreted in both ways—I agree.

JM: So, the judge invoking Shakespeare, that brought you to the play?

MW: Yes. I saw that you underlined “we are not here acting a play” in your copy of the book. We exist in the play. We are the play.

JM: It’s like this is reality.

MW: Yeah, this is reality. The performance is reality. I went to Oberlin College as an undergraduate and everyone was talking about Judith Butler all the time and the performativity of gender. If your gender is performed and is socially constructed, people are responding to it and interpreting and misinterpreting it. Butler writes, “Gender is the repeated stylization of the body, a set of repeated acts within a highly rigid regulatory frame that congeal over time to produce the appearance of substance, of a natural sort of being.” In the ten days while Bridget was ill and before she was murdered, her “repeated acts” or “stylization of the body” was unusual, her illness became a performance that made her suspect. People began to wonder, what “natural sort of being” was she, woman or fairy changeling?

JM: I was thinking a lot about the judicial treatment of victims and what we expect from victims, and I was making connections with Susannah Dickey’s ISDAL. The emphasis being on the woman and what the woman did, which is then heightened and dramatised through the trial and the play structure in your book.

MW: There’s a great essay by Fran Lock called “The Workshop/The Witch”. Bridget is sometimes called the last witch burned in Ireland, but that is a bit sensationalised and it came through the newspaper coverage in 1895. Bridget is more associated with a fairy changeling, a swapping of identity, but because she was killed by fire I think the overlap between the fairy changeling and the witch—there’s a relationship there. The witch is helpful in putting Bridget in the context of other possible witch figures, women we see today as powerful, independent, often reclaiming them—Bridget made her own money from keeping hens and was a skilled seamstress. She was childless, which relates to the association between the witch and the crone, the post-menopausal or perhaps infertile woman. Lock talks about how without context the witch’s suffering can be “exceptionalised”—without context, without class, without culture, she can become the “white lyric witch”. We’ve seen a huge boom in “Witch Lit”, which is exciting, but it poses questions about who we recognise as a witch and how these stories are reimagined. How is the witch classed, raced, etc. So, I think Lock’s piece is really important. I felt that I didn’t want to exclusively write from Bridget’s point of view. I immediately felt that the story required lots of different points of view, which is interesting because Bridget is the main character…It’s hard to articulate that desire for multiple perspectives because it goes so far back.

JM: There’s lots of people acting “upon” her, right? So, it makes sense that as the reader we would get to see some of the thoughts or conversations that might have been swirling around.

MW: All the forces acting on Bridget—misogyny, ableism, patriarchy—those are still acting on all the other women. I don’t want to make Bridget exceptional, so I did want to give voice to the other characters and ask how they felt watching this happen. What could do they do? What could they not do? For example, I wrote the poem “A Butter-Woman” quite early on about the neighbour William Simpson who has the keys to Bridget’s house, and I wrote the poem about William’s wife Minnie (“With Parted Eye”) very late on. Part of that was that I started with the most essential characters and as time went on I tried different voices. Moving from major characters to so-called minor characters was a challenge. Minnie Simpson is called as a witness and she gets a small part in Bourke’s book, but that minor character provides a really important voice towards the end of my book. Minnie was ten years older than her husband, which was seen as unusual by the community. She had two daughters. When she was visiting the ill and bed-bound Bridget, how was Minnie seeing herself reflected back? Or was she thinking about her own daughters? Was she worrying about her future or their own?

There could have been a fear of maybe associating with Bridget. From a contemporary perspective, we might want to see poems expressing female solidarity with Bridget, but Minnie Simpson was probably very afraid of what that association was going to do to her own life. That is definitely true of Bridget’s cousin Johanna Burke. She turned Crown witness in this story, and Bourke writes about how she probably did that because she had five or six young children. She was arrested initially and then turned witness to protect herself and her family.

JM: I think that’s one of the strengths of the multiple voices and the play structure, it allows the reader to see how power and fear operate across multiple layers of communities, from minor people to central characters. It allows us to see how insidious this can become and that culture of fear, which has deep roots in Ireland, how pervasive that can be and the impact it would have.

JM: I’m just realising I’m running out of parking time! Do you want to walk and talk? MW: Yes—in the spirit of fieldwork!

Walk from Established Coffee to the car:

JM: In the book, you explicitly foreground your own position and perspective by having the prose parts of field notes or research notes. You are showing the reader where you are coming from. Did you think it was important that your own voice was explicitly in the book in that way? I’m curious about how you think of those parts. I thought of them as prose pieces, but I didn’t know exactly how to characterise them. I’m thinking about them as interruptions—I often think about poetic form in those terms, what I call “a poetics of interruption”.

MW: I took the research trip and I didn’t know what it would be like…I knew I wanted to try to write about the experience but I didn’t know what would happen. So, every time something happened I would get back in the car and transcribe it. It’s non-fiction on the events as they happened, with small adjustments. I wrote it as one long essay, although I don’t write prose, and it had these section breaks and I ended up splitting it up over time. As the book grew, I thought about how each individual piece could relate to different voice poems, and how those voices alluded to different places and where that would all intersect. The trip was great, but I felt so much unease about the role of almost anthropologist—which is historically colonialist, extractive, white, all those things—and I have my accent. I found it fascinating to do the trip with my partner who is Irish. There were things I didn’t want to ask people who were living in and around Ballyvadlea, especially in my own accent. Also, there is a moment in the book when I talk about the people in the graveyard digging the grave, which was completely surreal to see, and there’s a line that says “I’m wary of asking men questions while they are holding shovels or any other heavy implement”. So, it’s both an Irish and foreigner dynamic, a gender dynamic, who can ask what, who can say what…if my partner approaches these men and he asks them this question, what will they say to him. And what happened is that they asked him if he is from the North. And he said, “I’m a County Down man”, so it’s like are you locating and identifying yourself by North and South, or by county?

JM: It brings out some tensions that are already in the book maybe.

MW: There was so much unease for me as a foreigner and I was willing to reckon with that and put that in the book. I’m not trying to draw any parallels between myself and Bridget, but I recognise that her story is a story of difference and an identity that is suspect. The ways in which those play out and the context between myself and Bridget are totally different, but there is some part of me that was drawn to this project and able to write about it because I have experiences of being different. People hear me speak and they have questions, and people maybe would have met Bridget and have said “you’re earning your own money, why aren’t you at home with your kids? You don’t have any kids? Why don’t you have any kids?”. So, identity can prompt questioning, which can be due to curiosity or suspicion, and those answers and questions can lead to any number of interpretations.

JM: I think those questions and interpretations are what’s great about making the work in the way that you have, and relevant to this moment when so many poets have been making archival work that burrows into different people’s lives—and it’s important to remember that it is poetry. It is an imaginative space about a real person.

Drive to the Leonardo Hotel:

MW: I got asked a question recently about my book, about whether all the people in it are real. And I was shocked by that, because all the people are named and they’re all real. All the stage directions are the real details. I pulled all the details from the research, like Bridget’s father was losing his sight, and Badger the dog barked at someone who was visiting the house after Bridget’s death. All those people and details are real.

JM: I think I had that question too. I was wondering whether some of the characters or details were imagined. Do you explicitly say at any point, or in the notes section, that all the people are real?

MW: No, because you get so deep into your own work—I didn’t think to state it so explicitly. I heard Martina Evans reading recently and in her book Now We Can Talk Openly About Men, there is a note that says something about how the women are fictionalised but they exist in a historically accurate 1920s Ireland.

JM: It brings to mind CD Wright talking about the “borrowed-tuxedo lining of fiction” at the beginning of One With Others.

MW: Yeah, and I was reading Evans’ book thinking that it reads as real and the world is rich and you could think that these named characters are real. Then I realised that people could be reading my book thinking that it’s poetry, it’s imagined, it’s fabricated.

JM: I think the play structure maybe heightens that inclination, maybe because of the “character” element. But how concerned are you that the readers know that it’s fact?

MW: Once you publish a book, it’s finished for now, finalised for now. Maybe in the future there’s an addendum, or a second publication. But you suddenly think: I should have put that note about the characters being real…

JM: But the book is a moment in time—it’s not done. It’s not over. There’s conversations like this, and there are different ways that it continues. It doesn’t have to encapsulate every single thing that you could have or might have done…I always think of Maggie Nelson’s Jane: A Murder which reflects on a conversation between the poetic speaker and a family member who says “What will it be, a figment of your imagination?”. And, of course, it is going to be partly a figment of our imaginations…

MW: And also research and fieldwork and history and documentations and so many things…

FURTHER READING

Bourke, Angela. The Burning of Bridget Cleary. PIMLICO, 2006. Boully, Jenny. The Body: An Essay. Essay Press, 2002.

Butler, Judith. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory”. Theatre Journal, vol. 40, no. 4, 1988, pp. 519-31.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble. Routledge, 1999. Dickey, Susannah. ISDAL. Picador, 2023.

Evans, Martina. Now We Can Talk Openly About Men. Carcanet, 2018.

Farge, Arlette. The Allure of the Archives. Translated by Thomas Scott-Railton, Yale University Press, 1989.

Hoff, Joan and Marian Yates. The Cooper’s Wife Is Missing: The Trials of Bridget Cleary. Basic Books, 2001.

Lock, Fran. White/ Other. the 87 press, 2022.

McCarthy, Adrian, dir. Fairy Wife: The Burning of Bridget Cleary. Wildfire Films, 2005. McGuckian, Medbh. Drawing Ballerinas. Gallery Press, 2001.

Morrissy, Julie. Radical! Women and the Irish Revolution. National Library of Ireland, 2022.

Nelson, Maggie. Jane: A Murder. Soft Skull Press, 2005.

NourbeSe Philip, M. Zong! As Told to the Author by Setaey Adamu Boateng. Wesleyan University Press, 2008.

Rukeyser, Muriel. “The Book of the Dead”. U.S. 1, Covici Friede, 1939. Poetry As Commemoration. www.poetryascommemoration.ie/ Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. Wordsworth Editions, 1992.

Wright, C.D. One With Others. Copper Canyon Press, 2010.