Jailbreak: Great Irish Republican Escapes 1865-1983|James Durney|Merrion Press

Jailbreak is the enthralling tale of twenty-three major republican breakouts

by James Durney

Jailbreak: Great Irish Republican Escapes 1865-1983 tells the stories of the many successful republican escapes over these years, but also the elation and the heartbreak that followed. Jail escapes have always fascinated us and a stock of popular movies such as The Great Escape, The Shawshank Redemption and Escape from Alcatraz have fuelled that interest. Jailbreak songs are also popular, and the foundation of many popular jail ballads is included in this enthralling tale of republican escapes.

Jailbreak provides an insight into twenty-three major republican breakouts, the characters involved, their age, their political experience, and what happened to the escapees afterwards

Over the last 150 years, thousands of men, women and young boys have passed through the political imprisonment system in Ireland and Britain. Many chose to flee that system of their own accord. Jailbreak provides an insight into twenty-three major republican breakouts, the characters involved, their age, their political experience, and what happened to the escapees afterwards.

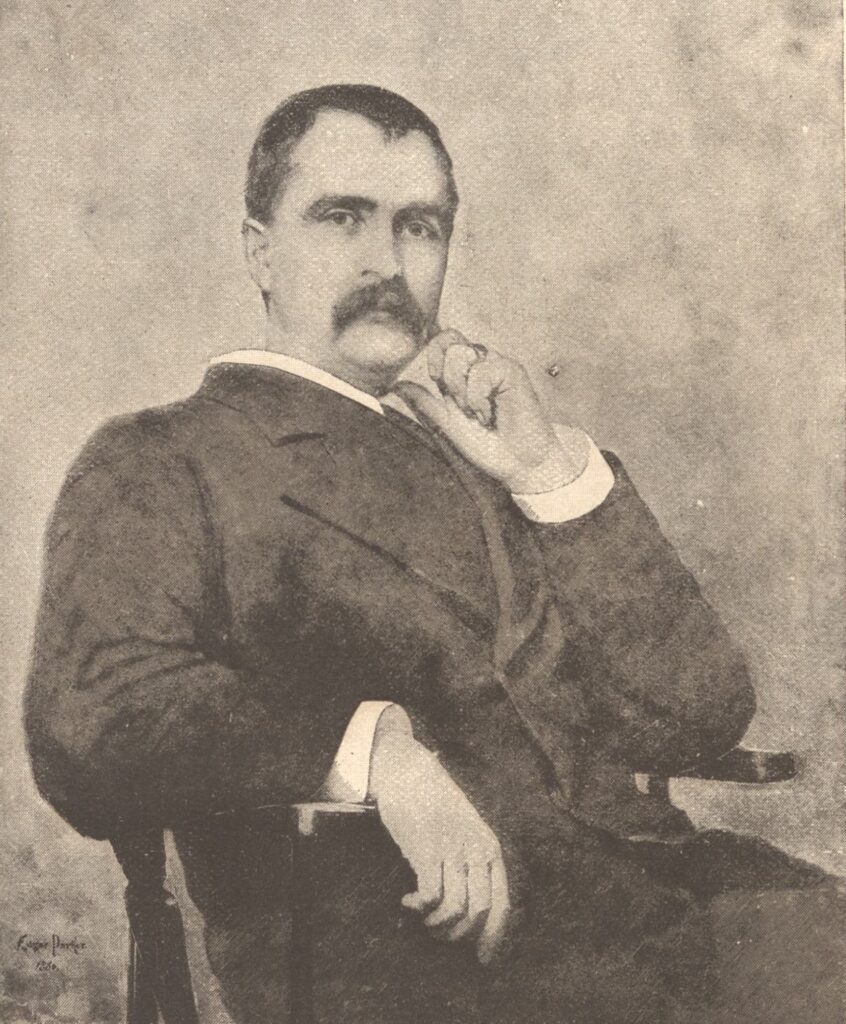

Fenian leader James Stephens’ flight from Richmond Prison in Dublin concluded one of the shortest stays of detention in the history of Irish republican escapes. He was arrested on 11 November 1865 and within twelve days was a free man. The daring operation proved a propaganda coup for the fledgling separatist movement, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), founded on St Patrick’s Day, in 1858. Two of his rescuers, John Breslin and John Devoy, followed up this daring escape with an audacious rescue on the other side of the world when they organised the escape to America of six Fenian prisoners from Fremantle in Western Australia in 1876.

Michael Collins’ biographer Piaras Béaslaí, a two-time escapee, said: ‘It is a theorem with prison-keepers that, while a man may serve twenty years in prison without once thinking of escaping, he who has once escaped is certain to attempt it again.’

This opinion was justified in Béaslaí’s case, for he subsequently escaped five months after having been recaptured after a previous escape. He was not the only one. Tomás Ó Maoláin escaped through a tunnel from the Rath Camp in September 1921, and again went out through a tunnel from Tintown Camp in April 1923. Eleven unsuccessful escapees from the Curragh’s Rath Camp later organised the mass tunnel breakout from Kilkenny Jail in November 1921.

There were risks to escaping, too. Patrick Bagnall escaped from Newbridge Barracks in October 1922 only to face a firing squad two months later when he was recaptured under arms with the anti-Treaty Rathbride Active Service Unit. Over the years many other escapees returned to active service only to be killed in action. Within a year of escaping from the Military Detention Barracks in the Curragh, in 1972, Paddy Carty and Michael McVerry were dead – killed while engaging in actions against Crown forces. Three of the 19 successful H-Block escapees from the ‘Great Escape’ of September 1983 were also subsequently killed in IRA operations.

Patrick Bagnall escaped from Newbridge Barracks in October 1922 only to face a firing squad two months later when he was recaptured

Most escapees returned to active service, but others faded away from view, rarely to be heard from again. The stress and strain of imprisonment took its toll on the mental and physical health of political prisoners. Some were imprisoned in three different campaigns – the Easter Rising period, the War of Independence and the Civil War. Others from this period were jailed again in the decades after. Frank Driver was first jailed when he was 16 in 1922, and was imprisoned in four more campaigns, taking part but failing to escape from the Curragh Camp in the big breakout of December 1958.

On 21 November 1920, a day forever known as Bloody Sunday, Frank Teeling was one of a group of IRA volunteers who entered 22 Lower Mount Street, Dublin. They were looking for Lieutenant Henry Angliss and Lieutenant Charles Peel, who had been involved in the shooting dead of republican John A. Lynch in the Exchange Hotel. Lt Angliss was shot dead in his bed, but Lt. Peel, on hearing the shots, blocked his bedroom door and survived. In an ensuing gunfight that followed as the IRA men escaped, two Auxiliaries were killed. Teeling was wounded and captured as he covered his colleagues’ retreat. One of the Auxiliaries held a cocked pistol to Teeling’s head—he was giving him to the count of ten to name his accomplices or die—when Brigadier-General Crozier, Commander of the Auxiliaries, arrived on the scene. He told his men he had no objections to Teeling being executed, but it would have to be done legally.

Teeling was court martialled and sentenced to death. He was held at Dublin’s Kilmainham Gaol, where he faced the hangman’s noose. Two other prisoners, Ernie O’Malley and Simon Donnelly, were also high on the British death list so all three absconded on 13 February 1921, with the help of two British soldiers on guard in the jail. At the last-minute Vol. Paddy Moran decided to take his chances and stay behind, but he was hanged a month later.

When eleven escapees from Derry Jail were recaptured at St. Johnston after crossing the border into Donegal were told they were going to the internment camp at the Curragh, the eleven escapees said they would rather go back to Derry Jail where conditions were better than those in Co. Kildare. The Curragh internment camp was under military control, and it had harsher discipline and a poorer diet.

Conditions in most jails or camps were never good and by 1971 Crumlin Road Gaol, known as ‘the Crum’, held 860 inmates, mostly due to the outbreak of The Troubles. Political prisoners were held on C Wing, sometimes with two and three in what used to be a one-man cell. The prison conditions became so bad Terence ‘Cleaky’ Clarke said darkly, ‘The Crum is so bad it would put you off going to jail.’ Maybe that is why the Belfast IRA unit known as the M60 Squad decided to leave in the summer of 1981.

In early June seven Belfast IRA members were within days of their trial on charges of M60 machine-gun attacks that had left two members of the Crown forces dead and three wounded. Two weeks earlier, two small .25-calibre handguns broken down into separate parts were smuggled into the prison and assembled in the jail. Within hours of the jailbreak the escape became known as ‘The Great Escape’ and the escapees as ‘The A-Team’.

There were many more attempts to break free from Crumlin Road Gaol before it finally closed its doors in April 1995, but the M60 Squad escape from the Crum was the most audacious jailbreak of the period. That was until 1983, when there was another Great Escape, this time from the H-Blocks of Long Kesh, when prisoners took over an entire block, loaded 38 men onto a food truck and headed out the main gate.