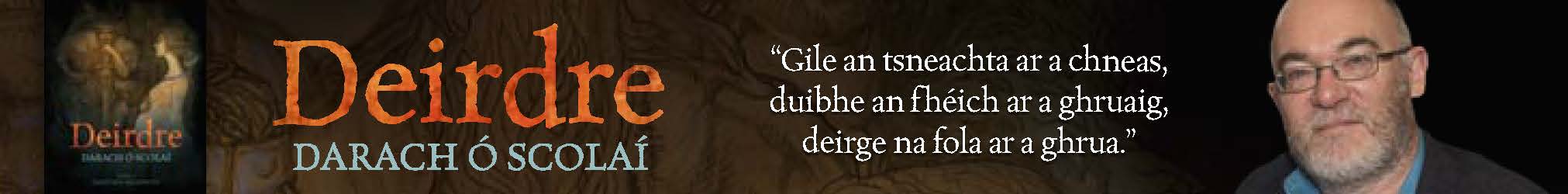

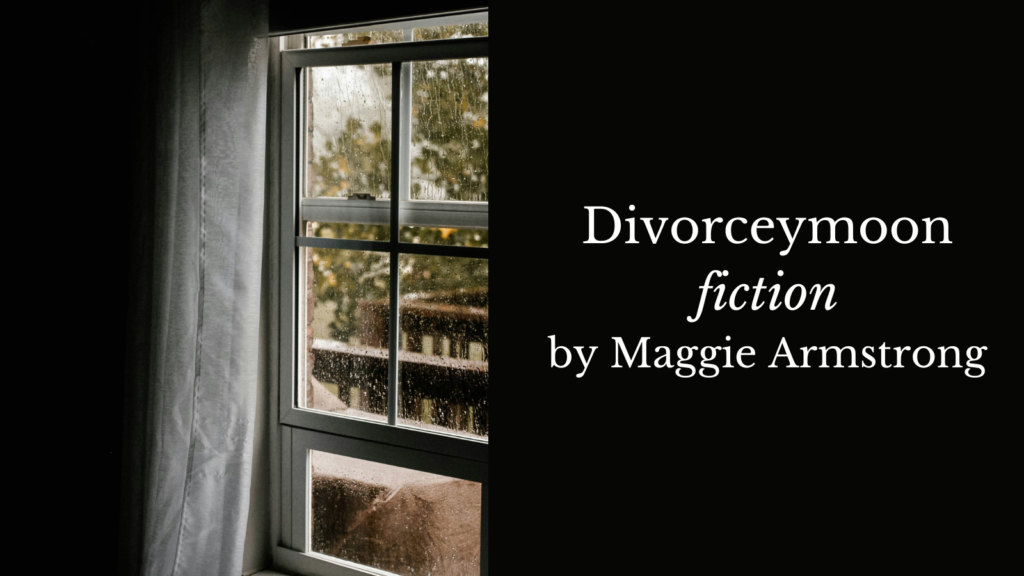

Divorceymoon

by Maggie Armstrong

One thing I really object to is the low credit alarm they’ve built into the Prepay Power electricity system. Fine, they need to tell you when the money’s running out but that thing makes an awful sound. A kind of dull ambulance wail in two long reedy notes, almost elegiac, but oddly buried, muffled, a mermaid in a sewer. A mermaid who can’t sing. The low credit alarm played on and off those years and it added greatly to my strong suspicion that we could not afford to have broken up.

But it had happened now, it couldn’t be reversed, not without a lot of histrionics.

The alarm went off at 9.23 at night just recently and I thought, can you please do that at a sociable time? It seemed very antisocial. The evening had nearly been completed. The boy was asleep in the wrong bed, the one that is supposed to be mine. The baby and I were reading Peepo! and she was becoming very placid. That’s not her usual state, but it’s one she reaches every night at the merest mention of Peepo! She sits upright and goes quiet, waiting to be reunited with a winsome baby in a jumbled house in London, and their ruddy pink extended family who help out with chores and bedtime: the sister who is so kind, the grandma so industrious, the father so good-natured and so modern.

It’s the same story every day she wants. Nothing changes in the story of this pink, round, winsome ’80s baby’s fun-packed schedule but maybe she’s finding something new.

She was entering her dream state. The low credit alarm pierced through the house and her eyes darted. She sat up and looked at me. I waited. The alarm went, and I’ll do my best here with an awful sound: eee-aaa-eee-aaa-eee-aaa. It continued, and I felt that to be here in this room was unimaginably annoying. It wasn’t like it was the first time I’d heard it that day. And it wasn’t quite despair that filled me, nothing so luxuriously fatal. More of a tormented wintry numbness settling like some kind of white mist between my temples. Or like nothing at all between my temples, nothing behind them, nothing in front of them but the wall, scrawled with pictures that don’t come off with Dettol wipes. At least the day was over, or almost over. I went down and pressed the star button: ‘Stop low credit alarm’.

Sometimes it occurred to me that other parents were putting their children to bed. I saw them in the shadows of the room, telling stories in soft voices, placing down a teddy bear, switching on an IKEA cloud night light. I felt left out by their efficiency, but comforted to think there was such order being upheld somewhere. Such rigour and such clockwork. The way it went for us was my children put me to bed. They were able to do that, just by being who they were, rummaging and playing games while I lay flat and decided that I had no strength to get up. They shrieked, became hysterical. The little one threw books, and just when she was meant to yawn and close her eyes she jumped down, emptied her drawers of fancy clothes, tried on my highest heels and pranced across the floor.

The evening had no end. But like every evening, I heaved the boy into my arms and steadied him, out the door and then across the hallway, like a thundering pietà, to the box room, where a note Blu-Tacked to the door reads ‘inter at ur risk’. I pressed his cheek with a kiss so fierce it creased his brow, a stolen kiss that made up for all the kisses he had started to recoil from. When I returned she was sitting up contentedly, ripping pages out of Peepo!

Two years ago I stood in the kitchen of the old house on a summer evening and said: ‘That’s it for us. Goodbye.’ The way I said it this time, it sounded different. I almost believed it. Less clear entirely was how to put it into practice, pregnant as I was. What about our children, what about his children? It was up to me alone and I had no idea what to do. The maternity hospital arranged a phone call from their social worker. ‘There’s a saying: paper doesn’t refuse ink,’ the social worker told me in a firm and trustworthy voice, and I was immediately in thrall. ‘Write down your options then come into me on the 5th and we’ll talk it through.’

There was a heatwave, and the 5th seemed an eternity away. Every day I slumped around the house with a notebook, writing lists, cost benefits, spider graphs that sprawled until the page stopped. I sat awake at night making bullet points and underlines and arrows, with love hearts here, stars there. The future scattered into a list of possibilities that were each so differently disastrous I started wondering about maybe doing nothing whatsoever. I started doing odd things: ordering swatches of new curtain fabric, buying pink sheepskin slippers, and boxes of salt caramel truffles; and reading the voluminous memoirs of Peggy Guggenheim. She and her first husband had shouting fights, and when he got aggressive he would rub jam on her face or plunge her head into the bath.

I was shocked. That’s never happened me, I thought. So maybe it’s all good?

‘What is your benchmark,’ the social worker asked me on the phone before the appointment, ‘for a good and healthy relationship?’

And I thought, I don’t know, but could you just tell me what to do please? I held the measuring tape to the windows and ordered linen curtains for all the bedrooms, then sympathetic bedspreads – carried sets of them through shops, staggering now, with pelvic girdle pain. What I wanted was somebody to come and tell me what I was supposed to do. It didn’t seem a lot to ask of anyone, and yet, silence roared at the predicament. I pictured a mother with two children in a rented apartment, bare cupboards, alphabet blocks, a laptop for Netflix. Eating our tea in McDonald’s. No thanks. What we could do instead was just continue. We had got used to it. The curtains were on their way, in shades of duck egg and olive green, one with boats. And I worried that it might not be too intolerable to continue. I knew by now that it is necessary sometimes for circumstances to become intolerable.

On a July morning I put the notebook in my handbag and took it on the bus to Merrion Square, where the National Maternity Hospital stands tall and redbrick like a biscuit tin full of surprises. It must have been the hottest week the summer had brewed up and there didn’t seem to be air conditioning. The social work department was set apart along a quiet corridor, through a creaky door into a two-chair waiting room where I sat facing a small glass bureau. A receptionist talked on the phone, fanning herself with envelopes. I poured myself a plastic cup of ice-cold water from the cooler and sipped. A heavily pregnant woman came and sat beside me, sighing loudly. She wore a short white denim jacket which, above her bursting pregnancy, served the purpose of a ribbon around a parcel. We smiled in a knowing way at one another.

The social worker had an office like a shoebox with no window and a wall of metal filing cabinets thick with black ring-bound folders. She asked did I have far to come, and I took my chair the other side of her desk, my foot knocking hers in the cramped space. Her toenails were shellacked a glossy raspberry pink, her sandals neatly latticed with tan leather straps. Her golden hair was neatly parted and tied back, and she had a natural tan, or just a great bronzer. Everything about her certain poise urged me to outline to her with only the greatest competence the predicament I was facing. The compassion on her face elicited a steeliness I could certainly maintain during the appointment. I told her I didn’t know what I was supposed to do. She listened carefully as I read from my notebook, first striking off option 1 – the pregnancy was too far advanced. The list went on a while – 5, 6, 7. ‘We can go and rent, or stay exactly as we are,’ I rattled, and she nodded, taking notes herself. Her pen was moving fast in what seemed to be a direct transcription of what I was saying. I could see her handwriting was very neat, covering the pages in clear dependable lines. It occurred to me she was just writing a duplicate list of options in her notepad. After an hour, she wished me the best of luck, but I’ve since wondered about the fate of that duplicate list, about what’s recorded in the thick dark folders stuffed into that exemplary filing system, her bookcase of broken families.

The baby arrived early on a Friday night in autumn. Her father held her to his chest and, for an hour or so, we were the luckiest people ever to fall in love. We brought her home that Sunday, and on the Monday morning I had the notebook back open under one arm, the baby asleep in the crook of the other, the door firmly shut.

As it turned out I got to skip through options 2, 3, 4 and 5 and go straight to 6: Go out and rent. I left the new curtains. Boxes teetered around us the morning I handed an envelope of cash to the estate agent of a house with no furniture; its electricity on a Prepay Power system, gas metre not yet installed, water supplied through a hose of mysterious origin. That morning, the boy safely in school, I put the baby in the middle of a Turkish rug which I had rolled up in the old house and taken with us, and lay down beside her. I gazed up at the ceiling until it seemed to cluster with bright stars and I was maybe delusional with happiness.

I had imagined it would be one big party but the plan had many cracks. The water supply occasionally vanished, the taps didn’t run. The great distances between the locations where we travelled were another unfortunate afterthought and every day, for miles, we sat on the tram, in the car, or on buses. We rushed to everywhere we went. Going off to school, I worried excessively about how we appeared to our respectfully quiet neighbours, thudding along the pavement, shoving the buggy along, late for the tram, the boy trailing behind us reading Captain Underpants as if he was anywhere else in the world. We’d roll home with the wheel of the buggy squeaking at every turn because it needed a little oil and I don’t have oil nor would I know what to do with oil nor do I want to know. The tram would shoot us back that afternoon and in the fuzz of coats, exchanging drab half glances, I needed at least one person to smile at my baby and say: she’s gorgeous. Or even just say it with a look. Usually someone would oblige.

In the afternoons, we were never sure what we should do. I had always pictured creative activities – smocks on, the newspaper down, the poster paints out. They were mixing up a muddy palette of paint colours, slapping down maroon rainbows in my imagination. In real life, the paints stayed in a tin they didn’t fit into, up in a cupboard much too small to house the tin. The boy would lie back on the sofa with his feet dangling in the air, remarking on all the things he doesn’t have, like Disney+ and a new basketball. Condensation dripped down the windowpanes and the evening beyond would seem unusually dank, the house increasingly cold. The baby would be beetling towards me on the floor and raising her arms to be picked up and the thought of finding dinner was impossible. I counted the hours until night, and counted the days until the weekend when they would go back to their father. I would boil the kettle and sit down for a cup of tea and then eee-aaa-eee-aaa-eee-aaa, the low credit alarm.

It went off in the middle of the baby’s first birthday party just as we produced the cake. I was still doing odd things: chilling bottles of prosecco, making top hats out of marshmallows and sweets, downloading Bumble, the premium subscription, on the same day deleting Bumble, asking for all my money back. I threw a party: everyone came, and the presents they gave were quicklky spread around the floor, mixed up with clouds of wrapping paper. The room was decorated with bunting and gold helium balloons and the table laden with buns and crisps and buttercream iced lemon cake and cocktail sausages and pizza slices gone cold and pink champagne and right in the middle of ‘Happy Birthday’ it pealed its dreaded warning of dwindling resources. I stumbled with my wallet, kind of sozzled, into the utility area whose single light bulb doesn’t work to press the star button, then pull out my bank card and key in my card number then do Two-Factor Authentication then the 16-digit Prepay Power code allowing for some typos. And I know what you’re thinking. You have a utility room? And can’t replace a lightbulb? Yes, and no. I can’t easily explain any of this and it is the reason I will tell the same story, every day – until it’s clear.

Those were days of celebration, when it didn’t seem extravagant to buy a box of wine or shoes or macaroons or book a little holiday abroad. Now I want the money back. I want to clear the room of people. The people are uninvited. The parties are all cancelled.

It went off on a Tuesday evening in November and I pressed the star button to shut it up. Surely we could find some reason to leave the house. We had to buy milk. We had to post a letter. We had to take the bottles to the glass recycling or buy pencils and a pencil sharpener or pots of slime. We shut the door behind us with the baby bound starlike in a puffa suit covered with the polar bears on sleighs, the wheels of the pram squeaking like a chorus of songbirds. We got off at O’Connell GPO where dusk had fallen, and the moon was out behind a shroud of silvery clouds. The air was crisp and cold, and people had been talking about snow. Nostalgic Christmas crooning played from speakers outside shops, the streets were too busy and they were both hungry. The baby was trying to escape her straps, and as we walked the boy’s features set into a mask of blank stoicism that made me guilty to observe. Gingerbread and candy canes and holly sprigs were stuck along the windows of McDonalds and screens flickered with meal deals. I knew this was the only place to go, and followed the warmth of sweet and fried things.

The boy rushed to a screen to tap in our order, quickly figuring out the boxes he needed to press. It was obvious he’d done this quite a bit already with his father. We found a table with enough space for a buggy and our number was called, and very soon, our meal was ready on a tray. Sitting across from us, a blonde-haired woman was asleep with her head tilted to the wall. Her friend, sitting opposite, was watching videos with beeping sounds on her phone, pulling chips out of a bag in long handfuls and stuffing them in her mouth. I unstrapped the baby and sat her on my knee. The boy opened his Happy Meal and took out a hamburger, chips, and the enclosed toy: a brand new deck of UNO cards. He gasped and clutched them. ‘Look!’ he said. ‘Fabulous!’ I said. The problems had been solved, all the boredom, because what could come between us playing UNO every night? I blew on a chip and fed it to the baby.

The woman next to us smiled and waved at the baby, her absent, watery eyes looking somewhere else. Her teeth were bent backwards and she was missing one at the front. I jostled the baby, pointing at the woman so the baby would smile back at her. The baby threw her chip on the floor. I blew on another, and I was wondering what to make of anything when a little woman with grape coloured hair asked if she could join our table. I wasn’t sure why someone would choose a table with such an amount of ketchup on it, but said ‘of course’. She wore a neatly buttoned quilted jacket and had a very orderly manner, placing down her bags and lining up her hamburger and cup of coffee. I unwrapped my McPlant and bit in.

‘Very cold,’ the old woman said with a foreboding look. ‘Isn’t it. The bills are insane.’ She nodded gravely, then shook her head with a kind of ire. ‘Christmas gets earlier every year. Now that’s a lovely baby.’

‘Thank you!’ I squeezed the baby tightly. Across the way, the blonde woman screwed an eye open, and started gathering up the plastic bags around her feet. She felt her way along the table, followed by the other woman. She was still drunk, and the ends of her tracksuit were streaked with blackish mud. For a while we could only sit in silence, looking at the empty table where the two women had been sitting. The boy yawned and stretched his fists out wide, then carefully packed his deck of cards into his coat pocket. I felt very grateful that they had been fed, at least until tomorrow. The woman said: ‘You know you won’t find better days than these.’ ‘Will I not?’ She shook her head. ‘No, you won’t. Don’t wish them away.’