‘From that day and hour all I wanted to do was work with books.’—Conor Graham celebrates 50 years of Irish Academic Press

by Ruth McKee

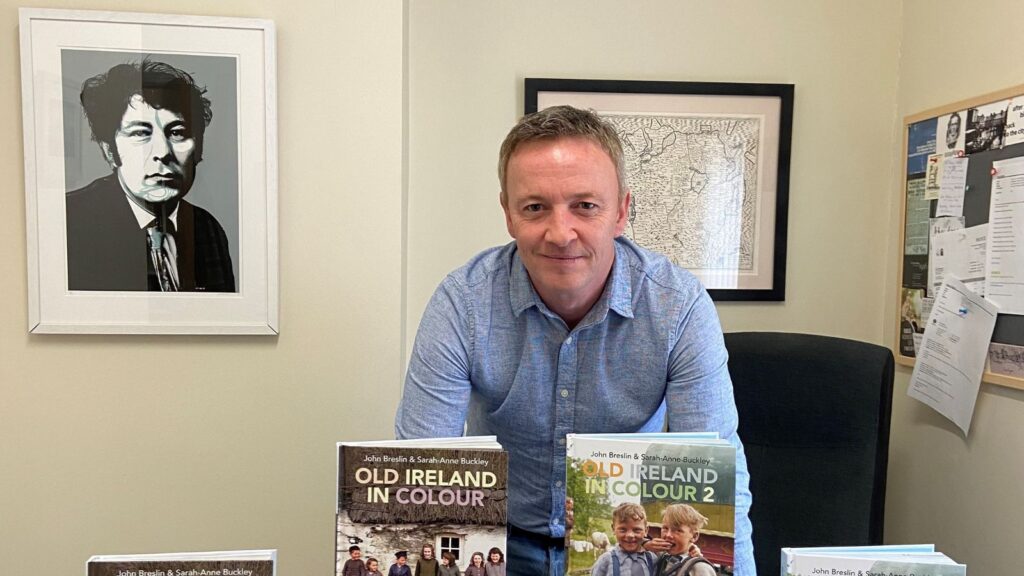

There’s a framed portrait of Seamus Heaney on the wall behind Conor Graham, Publisher at Irish Academic Press.

It all started with Heaney, back in Medbh McGuckin’s English class at Our Lady and St Patrick’s College Belfast in the 1980s. ‘Maeve covered a lot of Heaney,’ says Graham, ‘and I was mesmerised. It all made sense—he was dealing explicitly and directly with what was happening.’

Graham took Heaney seriously—’but school not so much,’ he says, with characteristic mischief. After some less than dazzling GCSE results he sat his A-levels in the College of Business Studies, then went on to Preston in the UK to take one of the first ever degrees offered in Journalism—but left disillusioned after one semester. He stayed in Preston, this time to study English Literature, where he found a home again in Heaney’s poetry, making it the focus of his dissertation.

Graham took Heaney seriously – ‘but school not so much,’ he says, with characteristic mischief

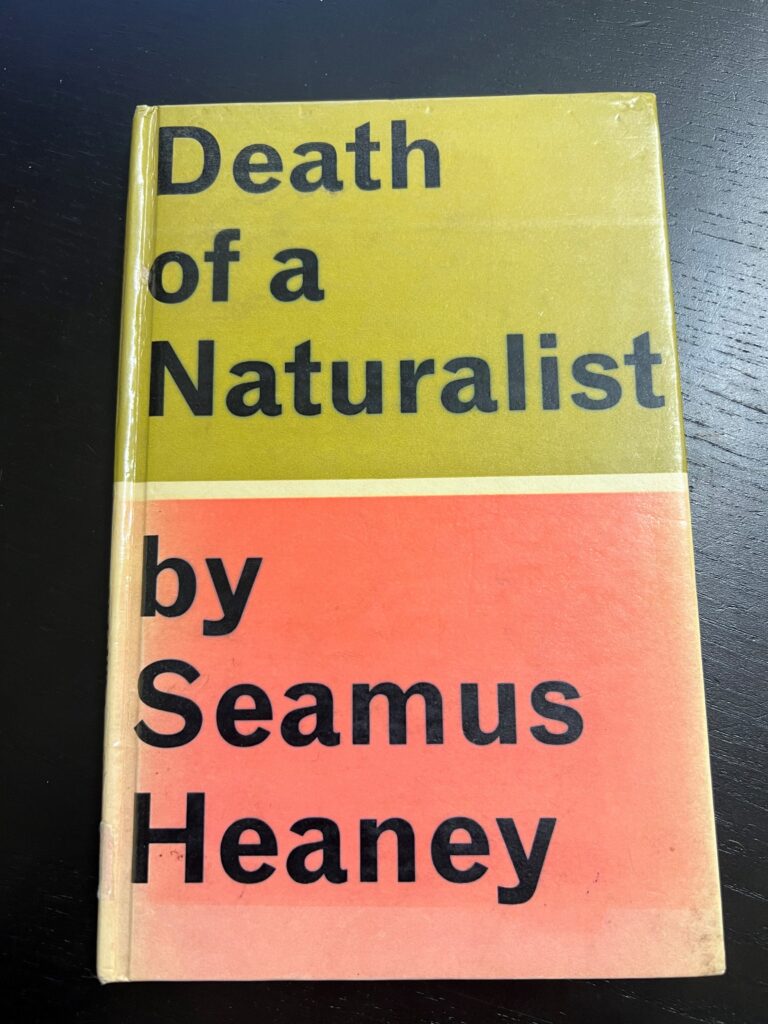

‘I saw Heaney’s trajectory starting with Death of a Naturalist—with its militaristic imagery used to describe the natural world. Then things slowly bubble to the surface in his bog poems, unearthing historical trauma to make sense of what was going on in the present. Then he deals with things more explicitly in poems like “Whatever You Say, Say Nothing”. Yeats wrote that the end of art is peace—as in the objective of art is peace. For me Heaney was trying to reach that through poetry, to make sense of conflicting emotions by capturing them, by framing them, by resolving them.’

It’s hardly surprising with this background that Graham’s professional life started in a bookshop—in Dillons, Belfast (now Waterstones) as Christmas staff in 1993. ‘From that day and hour all I wanted to do was work with books.’

A year or two later, it was clear that he needed to get to the heart of the industry—he wanted a job in publishing

The job in Dillons became full time after college, then he moved upstairs to corporate and library sales. When Waterstones bought the campus bookshop in the University of Ulster Coleraine, Graham applied for the manager’s role and got it—despite, as he says, ‘absolutely winging it.’ A year or two later, it was clear that he needed to get to the heart of the industry—he wanted a job in publishing.

He landed a job with McGraw-Hill, an educational text book publisher, where he became the sales rep for Ireland in 2000, a job which came with a company car and the flexibility to work from home, something not so common 25 years ago. He made top sales rep two years running and was offered the position of Acquisitions Editor for McGraw-Hill Europe.

This was again unfamiliar territory. ‘My list was computer science—I didn’t know the first thing about it!’ But he made the jump, learning about the subject, looking at the market, identifying gaps, then going after the right person to write the book.

I got to the point where I realised there’s more to life than money

If lucrative and prestigious, it was a demanding job, and eventually things took their toll. ‘We had two sets of twins at the time, and I was travelling all over Europe. I could be gone from Monday to Thursday. I worked hard and the salary doubled but the pressure was intense. After 18 months I had to get out of there, I got to the point where I realised there’s more to life than money.’

Finding a job at home where he could be close to his young family in Clane, Co. Kildare (where he still lives) was crucial, and when a vacancy opened up with sales agency Brookside Publishing Services in August 2002 he leapt at it. He stayed there for ten very happy years, working hand-in-hand with Michael D’Arcy.

Acquiring Irish Academic Press was life-changing. ‘It was never in my nature to own my own business, I’d seen what that type of pressure can do to someone and I never looked for that kind of responsibility. So it was a real leap of faith taking over IAP. Give me a manuscript, no problem, I know exactly what to do—but the management side, the corporate side, that was all new.’

He had no real capital at the time, but if anyone knows how to take a risk, make a deal and run with it, Graham does, and he acquired the company in 2012.

It was never in my nature to own my own business, I’d seen what that type of pressure can do to someone

‘It was an intense year. I was doing 2 ½ days a week with IAP and the same with BPS, along with a short stint as Commercial Director with New Island. I only had one full time staff member, and one part time—it was real hand-to-mouth stuff.’

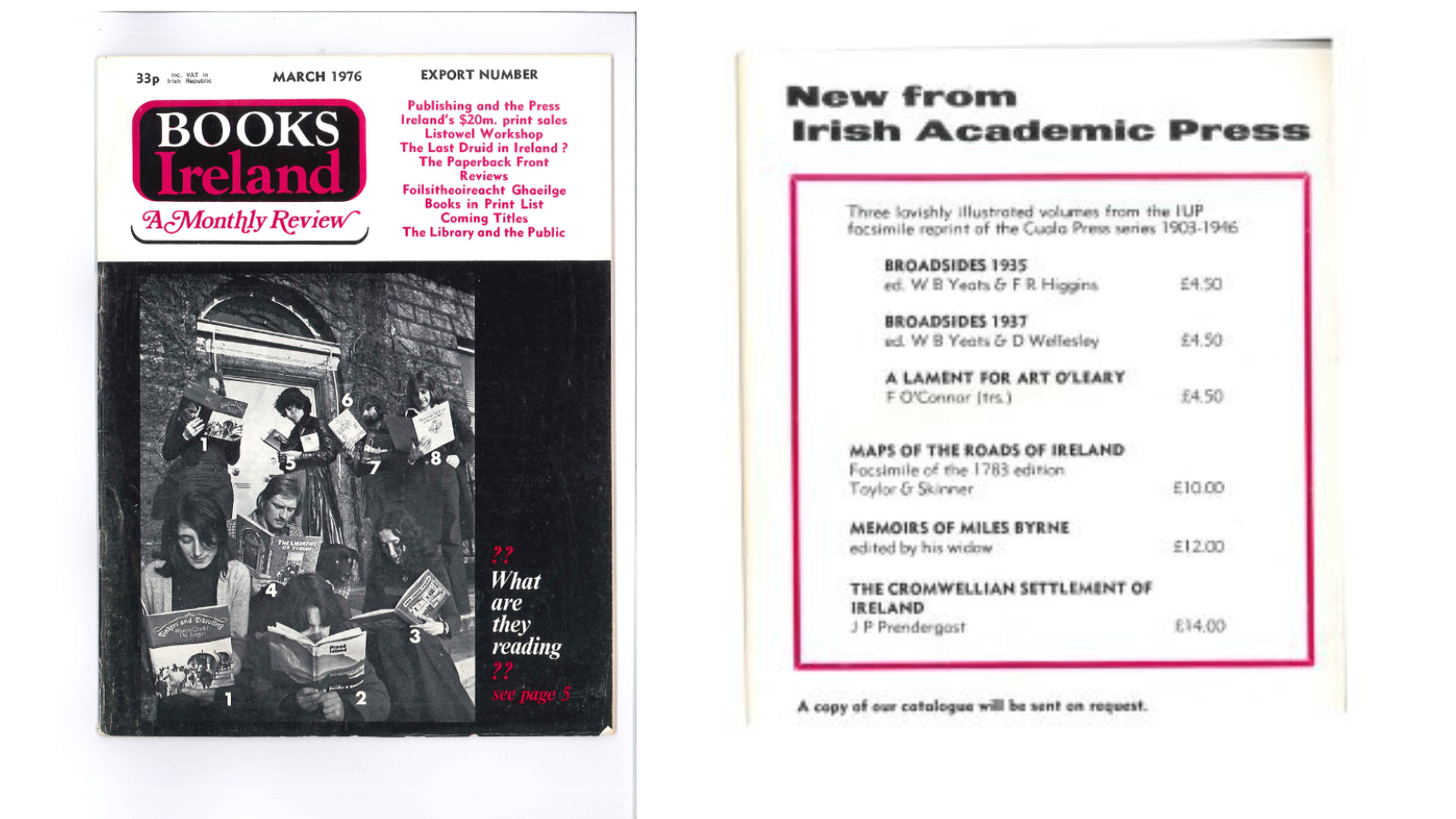

Graham has always been fascinated by the history of IAP, which began life in 1974 with formidable publisher Frank Cass after the collapse of Irish University Press (which was initially a vehicle for reprinting British Parliamentary papers and government documents).

Cass was an intriguing character, involved in many other ventures—and has a whole chapter devoted to him in Tony Farmar’s The History of Irish Book Publishing. Graham mentions some familiar names of industry professionals who started off with IUP and IAP, including Michael Adams and Martin Healey, who went on to set up Four Courts Press.

IAP began life in 1974 with formidable publisher Frank Cass

Graham pulls out some old documents. He explains that IAP acquired Cuala Press, set up in 1908 by Elizabeth Yeats with support from her brother William Butler Yeats, a press which played an important role in the Celtic Revival of the early 20th century. He leafs through original correspondence and contracts between IAP and the Yeats family, reading out some of the names on the Cuala Press list: Bowen, Synge, Kavanagh.

Merrion Press, the general imprint of IAP, was established in April 2012. ‘It wasn’t my idea but myself and Michael D’Arcy were heavily involved from the start. I took over in July 2012, and I’ve put my life and soul into it. The last 12 years at the helm have been fantastic. We have an incredible team who are class at their jobs, dedicated and committed, but I could have said the same five years ago. I run a tight ship and there is always pressure—but it takes hard work and pressure to drive growth.’

I run a tight ship and there is always pressure—but it takes hard work and pressure to drive growth

Given when and where Graham grew up, the influence of the Troubles on his list is understandable. ‘I think there’s still a deep fascination with what the hell happened over three decades, behind the news headlines, beneath the history books. It’s the darker corners, the untold stories that interest me. I was obsessed with what was going on when I was 16 or 17, the violence in society was overwhelming, and it’s never left me.

I was running about Belfast at that age and I was seeing it all. There were constantly bomb scares at the school. I had this great sense that I was living during an important time, that I was in the middle of a big story. You couldn’t help but be fully engaged with it—right through to the Good Friday Agreement. I remember standing in front of the City Hall in ‘98 when Clinton gave his famous speech. You knew this was seismic, that people would be talking about it for years.’

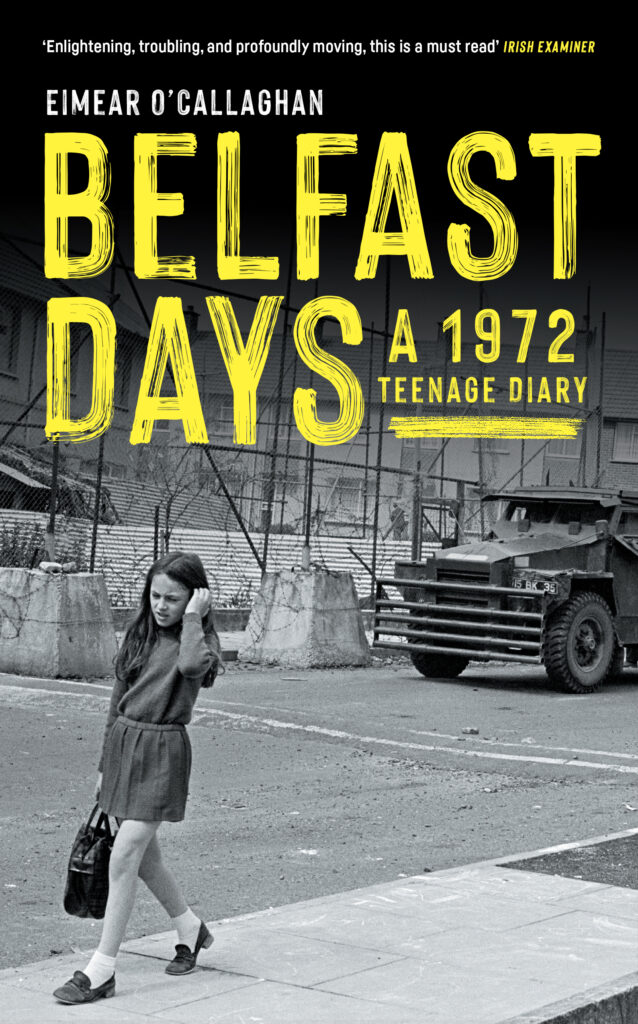

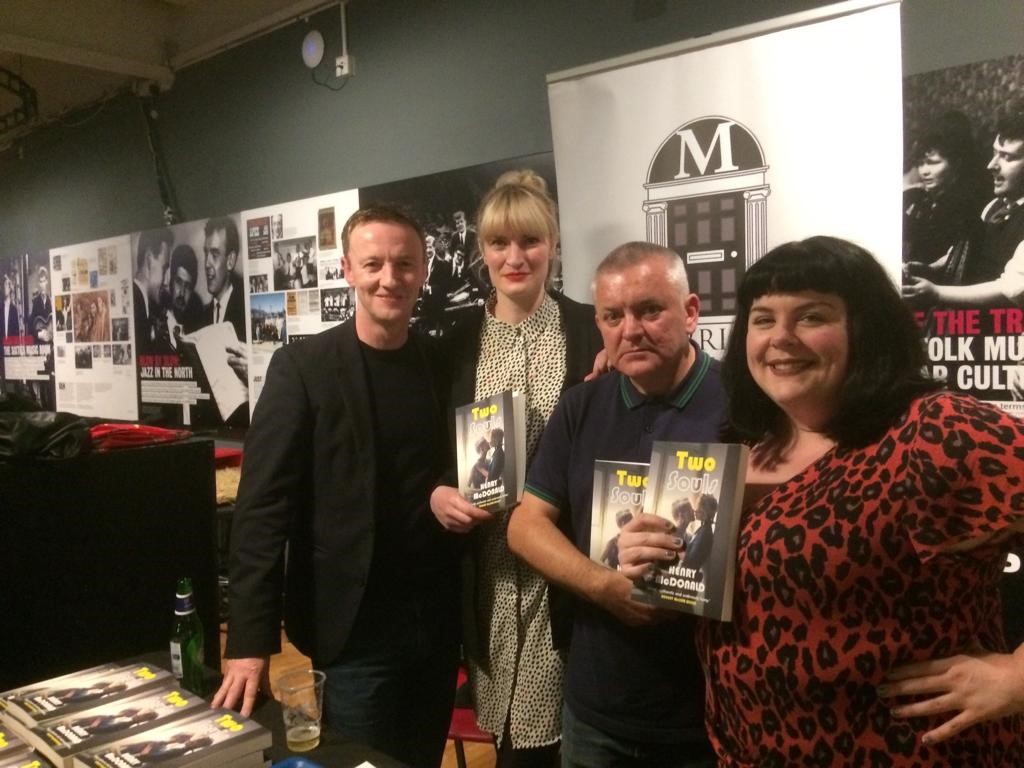

The first Troubles book that did really well was Belfast Days, by Eimear Callaghan. For the year of 1972 , the worst year of the Troubles, she kept a diary every single day. ‘It was really special, and is still selling well. Then with Stakeknife’s Dirty War – knowing that Ricky (the author Richard O’Rawe) had access to Scappaticci meant he could deliver a unique perspective on that story. We’ve had all sorts, from undercover agents to the head of the UVF, to Paddy Ryan’s book by Jennifer O’Leary (The Padre). And of course it was an honour to publish Dirty Linen by Martin Doyle.’

The best part of the job is the buzz and excitement when a book really takes off, which was the case with Brian Lenihan (ed Mary Rourke, Noel Wheelan & Brian Murphy) in 2014. ‘When you have a book like that your only problem is printing copies fast enough…it was an absolute thrill.’ Does he still get that feeling now? ‘Yes, especially if it’s a book you know is going to do well—we felt that with Burned by Sam McBride, and with Old Ireland in Colour. But on the flip side there are no guarantees—I’ve had authors on The Late Late Show and the book didn’t sell.’

When you have a book like that your only problem is printing copies fast enough…it was an absolute thrill

When it comes to the trappings that can sometimes accompany publishing, ‘shut up and sell the book’ is close to the mark for Graham, who nevertheless talks a good game, even if he says that sometimes he feels like he’s been winging it for over thirty years. ‘Sinéad McCrory who’s head of Waterstones now—I remember when I got the job at the campus book shop in Coleraine all those years ago going round to her branch on Royal Avenue and saying I was way out of my depth. Any time I see her now she’s like “well, he’s still here!”’

Graham has a good way with people and works well with authors, which he says probably plays a large part in being successful. So, has he any advice after 31 years in the industry? ‘Don’t over promise, deliver what you can, work hard.’

There are lots of highlights from recent years, such as publishing Paul Brady’s memoir, ‘one of the great joys of the job,’ or working with George Hamilton, ‘the nicest man on the planet.’ Lots to come too, including a new book from Martin Dillon, The Sorrow and the Loss, about the impact of the Troubles on women.

Don’t over promise, deliver what you can, work hard

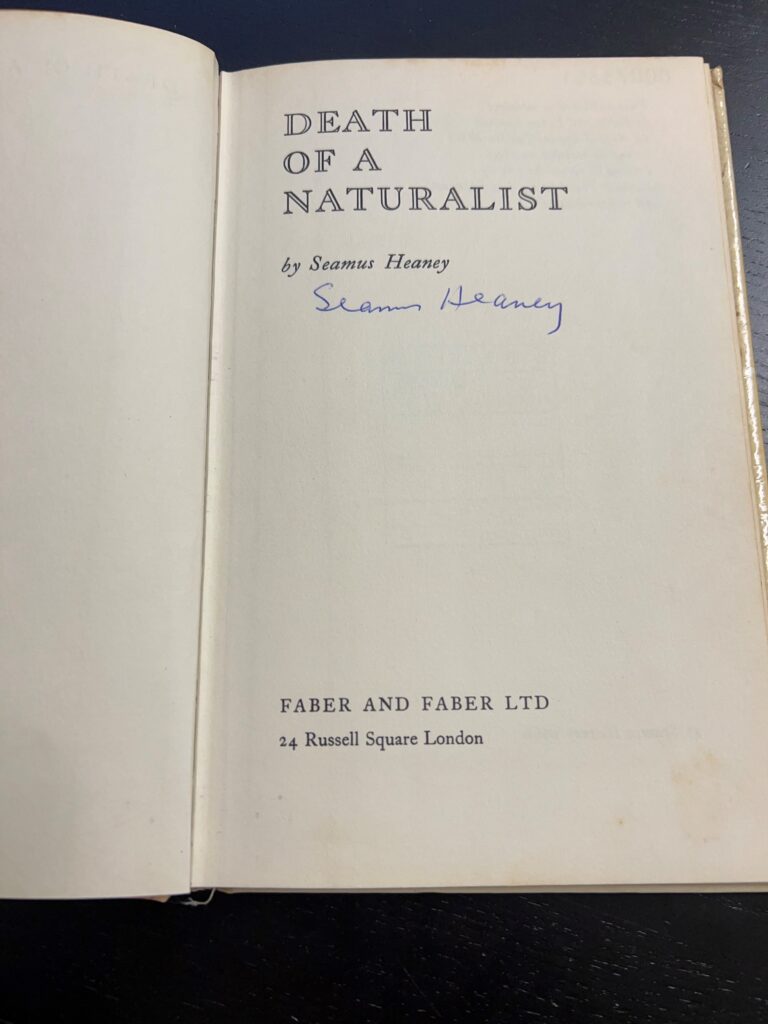

But it’s back to Heaney for things that have mattered along the way. Not long before Graham graduated, Heaney won the Nobel Prize. He remembers listening, rapt, to the citation live on Radio Ulster, later using part of it for the epigraph to his dissertation. In his Brookside days Graham got to meet the man himself—this is when Heaney signed his copy of Death of a Naturalist, something he treasures today.

Fitting then, that having a previously unpublished poem by Seamus Heaney in a collection of essays in honour of Peter Fallon has been one of the most meaningful moments of his career. Heaney died two weeks before he was due to launch the book at Trinity College Dublin. His wife Marie stepped in, and Graham remembers the night as being intensely moving: ‘we were all in tears.’

The poem is ‘The Dapple-Grey Mare’ translated from the Italian poem by Giovanni Pascoli. ‘I am hugely proud to have published him,’ Graham says, and I can hear the emotion in his voice. Then, ever the sales rep, ‘maybe I’ll sell it to Faber.’