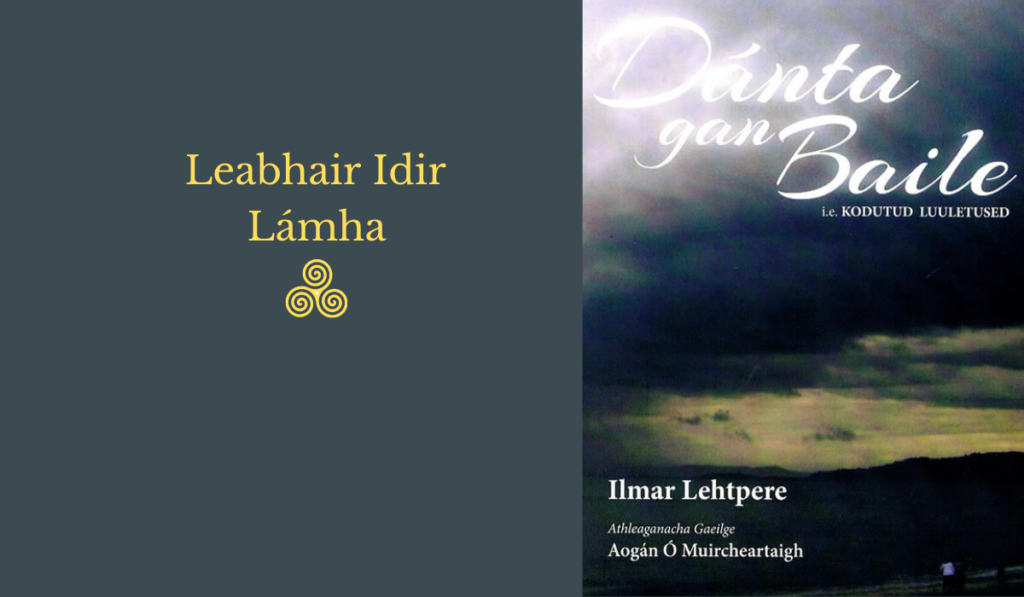

Dánta gan Baile, i.e. Kodutud Luulettused|Ilmar Lehtpere; athleaganacha Gaeilge Aogán Ó Muircheartaigh|Coiscéim| €7.50| ISBN: 6-660012-200269

by Cathal Póirtéir

This slim volume of poetry was a real and unexpected pleasure. I knew nothing of the poet, Ilmar Lehtpere, who was born in the United States and writes in Estonian—which along with English was the language of his childhood and of his father’s native country.

He is an accomplished translator and has published over twenty books in English and won a number of literary prizes. Many of his works are translations of the poetry of Estonian writer Kristiina Ehin. Aogán Ó Muircheartaigh, his translator here, has previously translated her work into Irish: Péarlaí Corraigh (Coiscéim, 2018).

The poems are love poems of one sort or another, mostly the poet’s profoundly felt and beautifully expressed love of his partner, but also for his parents, for Estonia and its language.

The collection is broken into a number of sections: Aithint; Rón-bhean; Brionglóid; Tír Dhúchais M’Athair and the final series of poems Bíonn na Réalta ag Síorathrú – An Grá agus an Galar Alzheimer.

There is often a dream-like, magical quality in his work as he imagines expressing his love for his wife in bird or animal form.

‘Níor thiteamar i ngrá nuair a casadh ar a chéile sinn/ ag an gcrosbhóthar faid leathshaoil ó shin – / d’aithníomar a chéile/ Éan ab ea sinn/ a chuimhnigh de gheit/ go raibh an dá sciathán aige/ seachas an t-aon sciathan amháin‘

While wings allow their love to fly, the depth of the seal-woman’s eyes open up the sea like a book whose pages are being turned by wind and wave, pulling the poet into deep secret sea caverns before his lover shape-changes into a swan in the evening, flying towards dawn, leaving him disturbed: ‘Id dhiaidh d’fhág tú creathadach/ corrach san aer/ is macalla do ghutha/ is tnúthán istigh ionamsa/ a bheith im chuid díot‘.

Bringlóid, a dream section, brings us to cold, bare northern forests where being naked in the cold or suddenly swimming in a lake takes nothing from the warmth of their love. With her, he feels no need to hide and discards animal disguises as he, in turn, shape-changes, becoming a bear, an animal she thinks will sense her love. He worries that her trust may be misplaced: ‘Tarraingímse orm/ mo chraiceann béir/ agus súil le m’anam agam/ ná gortóidh mé go deo thú’.

Lehtpere’s poems on his family background and language, while still dealing with a deep love, are tethered to the realities of family history.

His mother escaped across the treacherous Baltic Sea as Russian bombs, rather than waves, exploded around her ship, their aircraft using the Red Cross markings on a hospital ship as their target. The passengers’ pathetic screams for help still ring in her ears. His father’s stories keep Estonia alive for him. On visits he helps his granny protect chickens from a hawk, but prolonged absence from Estonia saddens him. It is where his language is spoken, where doors and windows can be left open, where the forests remain unconquered. A biographical note tells us he moved back there to work as a writer.

The poems in the final section of the collection, where Alzheimer’s disease threatens to change his relationship with his lover, are heart-felt and touching.

She tried to retain a hold her previous life: ‘mar a bhí gach aon ní/ fós ina áit féin’ but, distressingly for both of them, she often fails to recognises her husband, nor can he always respond effectively to her questions and nees. ‘Táimid ag luascadh le chéile/ ar bhruach ifrinn/ mar a mbrúnn an anachain/ isteach sa duibheagán tú/ arís is arís eile/ Níl ar mo chumas tú a tharrac slán/ is leanaim sios tú’.

The icy mists and shadows of this hell remind him of his mother’s flight to avoid Stalin’s Siberia, as he now faces the loss of what he holds most dear. His wife asks repeatedly about the health of her dead parents and to avoid distressing her repeatedly he tells her the they’re fine, hoping he isn’t lying to her. They are exiled now: ‘Ach ar deoraíocht dúinn anseo/ is é do dhomhan beag osréalach/ an t-aon áit/ a mbraithim boige/ agus grá/ an t-aon áit/ nach i m’aonar a bhím‘.

Ilmar Lehtpere’s wife, Sadie Murphy, was also a poet but it became difficult for her to find words, so when she breaks silence to request that her husband keeps visiting the hospital to help her, his reaction is understandable: ‘réabtar mo chroí arís/ ina smidiríní’. When she inquires where her friends have gone he can only reply with hugs and lies as the truth is too hurtful – she has Alzheimer’s but she is the forgotten one.

The poems trace her decline until she no longer knows or needs him, living in a care home as he lives in a flat. When the corona virus closes the home to visitors, he wonders if she will ever recognise him again. He only gets to spend her final speechless dying hours with her and a smile is her farewell.

Both the heart-rending subject of worsening Alzheimer’s disease in a loved one and the way it is presented here are deeply moving, even more so having read the earlier poems of love’s earlier excitement and experiences shared. Dánta gan Baile is a tribute to love and loss deeply felt. Aogán Ó Muircheartaigh is to be thanked for bringing Lehtpere’s wonderfully sensitive poetry to readers of Irish for the first time.