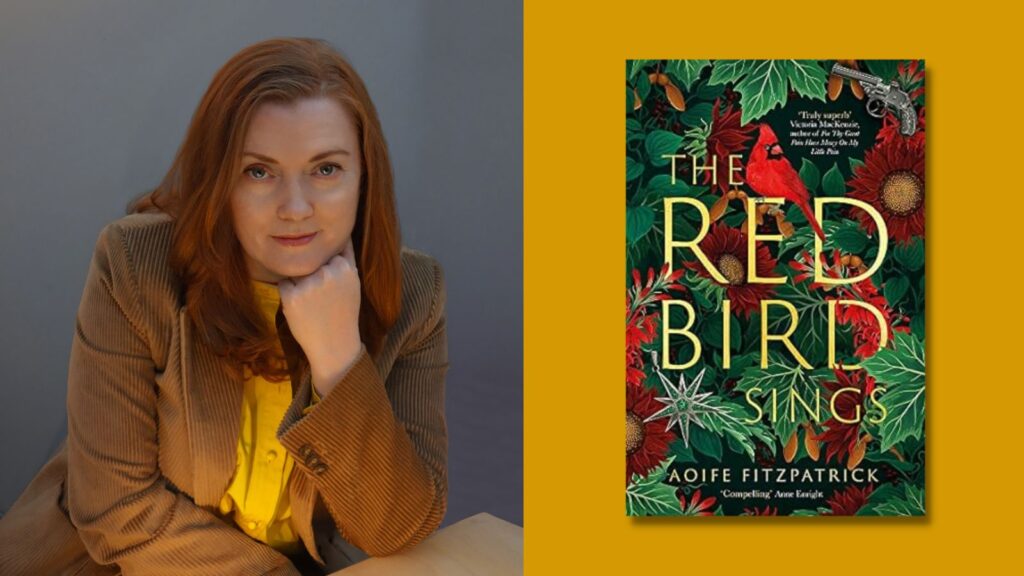

Aoife Fitzpatrick talks all things bookish for the companion series to our popular podcast, Burning Books

A prize-winning, spine-tingling gothic suspense novel based on a real-life murder trial in 1897 West Virginia

West Virginia, 1897. When young Zona Heaster Shue dies only a few months after her wedding, her mother Mary Jane becomes convinced that Zona was murdered – and by none other than her husband, Trout, the handsome blacksmith beloved in their small Southern town.

A book from your early days

I didn’t have many children’s books, aside from Well Really, Mr Twiddle by Enid Blyton. As I remember, it was mostly about kippers and beef dripping, but I read it out of desperation until it was in flitters. I was about seven when I discovered some clothbound classics on our bookshelves; mostly nineteenth-century fiction, including an edition of Hans Anderson’s fairy tales, translated from the original Danish.

I was stunned by the unhappy endings of The Little Match Girl and The Little Mermaid. It was my first experience of a book tapping into my private imagination, opening up the world, and helping me to process it.

Dog ears or book marks?

Mostly, I leave a book open, face down. But I also have an unshakeable, irrational belief that I will remember my page. I never do, and spend a lot of time riffling. If I’m reading on public transport, and happen to have a ticket, it will go into the book. I love finding old tickets inside novels.

A quote you can say by heart?

‘History is bunk,’ as spoken by Mustapha Mond in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (quoting Henry Ford). Three words of pithy satire, enduringly-relevant.

Best book someone gave you?

Under the Skin by Michel Faber. As with several of Faber’s books, there are passages in the novel that could seem preposterous if attempted by almost anyone else. But he writes with the kind of skill and conviction that makes anything seem possible, fashioning worlds and characters that are unfamiliar enough to push us towards new perspectives on our own existence.

I remember Under the Skin for one superficially simple scene where the protagonist takes her shoes off at the beach, and the observation of her experience is phenomenal. The film adaptation by Jonathan Glazer is terrific, but quite different from the book; it’s worth getting your hands on the printed work.

Do you lend without expecting a book returned?

Not happily. Like photographs, or music, or scent, books have enormous power to take you back to the time when you first experienced them. I sometimes browse my shelves, leafing through novels, just for this effect. It only works with a book bearing the marks of my own reading, and a new or replacement editions won’t do. The hypocrisy here is that I can become very attached to the books I borrow, and might be slow to return them. Do not lend me your books.

A book you return to over the years?

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley. Written in 1931, and set in 2540, this pre-WW2 satire is filled with prescient ideas about power, society and industry. Nearly 100 years on, it’s a terrific book to revisit as we grapple with technologies evolving at a faster pace than human beings.

In non-fiction, my copy of Victoria Finlay’s Colour; Travels Through the Paintbox is in well-loved tatters. It tells the rich history of the efforts of artists and artisans to reproduce the rainbow, and the impact their work has had on the world. There is wonder on every page.

The right book at the right time?

The Virago Book of Fairy Tales, edited by Angela Carter. I was studying Single Honor English at Trinity College during what I think—looking back—might have been the final years of an almost comically male-dominated curriculum. I wasn’t fully alive to the problem until Carter’s collection of folklore came along like a meteor blasting through the canon.

Its stories are feminist, not in theory, but in action. And their curation felt contemporary, reclaiming a space that I might be able to inhabit. It means the world to me that I’ve since been published by Virago Press.

A book that taught you something important?

How about useful? For some unknown reason, I once bought a book about different household uses for bicarbonate of soda. I still use the tip about cleaning silver—placing it in a basin with aluminium foil and some bicarbonate of soda before pouring hot water over it. It’s like performing a miracle.

A book that makes you laugh?

Molly Keane’s Good Behaviour is a hilarious masterclass in skewering social class and double standards. Shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1981, Keane (also known as M.J. Farrell) was at the peak of her powers in her late seventies.

I can’t leave out the posthumously published The Third Policeman by Flann O’Brien, with its wry, knowing, absurd wit. From the opening pages about the narrator’s relationship with the cute-hoor, Divney, right through to the novel’s denouement, it feels Irish in a way that might take me several PhDs to explain. Triple points because my grandfather was a sergeant in rural Ireland around the time of its writing, when the fettle of your bicycle was serious business.

A book you associate with a particular life event?

I picked up Anne Enright’s novel, The Forgotten Waltz, a few weeks after my mother died. A particular character in the book, recently bereaved, occasionally states, ‘and my mother is still dead.’ Terrific in its simplicity and frankness, it articulates how the loss of a parent might feel unbelievable yet monstrously true. It’s a brilliantly deployed line, and helped me in those days of moving from disbelief towards acceptance.

One of your own books you would save

The hardback of my debut novel The Red Bird Sings is quite lovely, with its wraparound illustrations by the painter Charlotte Day. I’d grab the copy I bring to readings.

A book you are reading now?

The research for my next novel, (also with Virago Press), is mostly non-fiction. I enjoy every minute of it, though it devours any time I might have for fiction. A recent novel that knocked my socks off is Soldier Sailor by Claire Kilroy, about a woman in the early years of parenthood. Its highly original in its immediacy, an eerily excellent simulacrum of consciousness. There are times when it’s the closest you might come to being fused with a character.

A book you’d leave in there to burn

I’d try my best to save them all, but I fear the last to be rescued might be The Lives and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. When I started college at seventeen, I don’t think I was mature enough to study it. And when you’ve had a bad experience with something, (for example, a certain brand of white rum on your 18th birthday), you might never want to try it again.

You can save one non-book item: what is it?

Maybe a guitar or two? My husband plays very well, I play very badly. The universal language of music might feel important as we watch the flames go up, trying to convince ourselves that we should have no attachment to material possessions, and that this inferno is the best thing that ever happened!