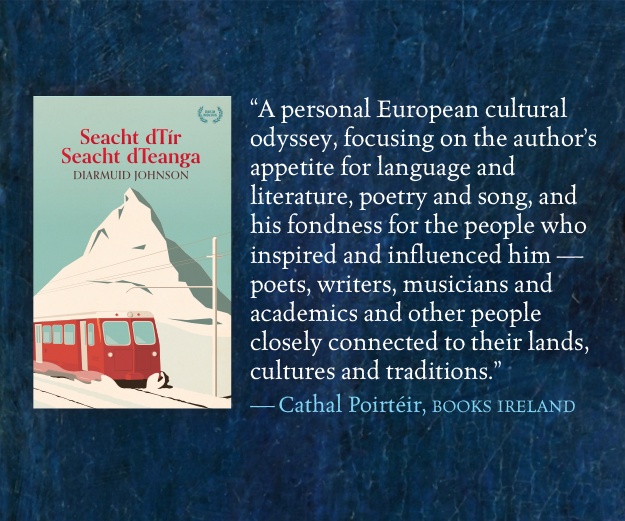

Catriona Shine talks all things bookish for the companion series to our popular podcast, Burning Books

‘Truly uncanny – a novel that marries the cosmic nightmare of Darren Aronofsky’s Mother! with the sociological portraits of Ken Loach.

Chapter by chapter, in the face of forces that are undeniable and elemental, Habitat’s domesticated world of rules and regulations deforms itself into something unsettling and eerily recognisable. I’ve never read anything quite like it.’

—Colin Walsh

A book from your early days

When I was maybe fourteen I spent a lovely summer holiday ploughing through The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde and subjecting my sisters to vaguely provoked witticisms. Sprawled across beds or rugs on the lawn, I remember it as a book I read stretched horizontal in endless leisure.

Dog ears or book marks?

I will dog-ear if I need to but favour a book mark – or French flaps. I usually have a few books on the go so the bookmark is whatever is at hand – for a while I used the tail of a whale which had fallen out of a pop-up book – and it’s often sufficient to rest a book upside-down, open to the right page. For a while I just remembered the page.

I like the quick game the eye plays to find the spot one left off at, nestling into the familiar details of the story before landing on that thin edge between what’s been read and what has yet to be discovered.

Do you lend without expecting a book returned?

People are not greedy. They simply don’t remember to return books. When you describe and hand a book to someone, that’s a story you’re telling them about the book, and, right then, they’ll imagine the essence of the book they’re holding. When they read it they will find that it’s something more than you described or they imagined; it will be quite a different book by the time they’ve finished it, not the one you lent them at all.

Best book someone gave you?

I got Annie Ernaux’s The Years for Christmas a couple years ago – a revelation, a life within time like I’d never read before.

A book you return to over the years?

I regularly dip into Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons and read a piece aloud. These are short texts that seek to evoke an object – a plate, a piano etc. – without describing it at all. Aloud, I can listen to my voice attempt to give the words emphasis and meaning where there is none in the usual sense. The same thing happens in a George Perec text where he’s coldly cataloguing the contents of a street or a room, but a sense of life being lived inevitably creeps in. I get a lovely feeling of resilience when humanity refuses to be ironed out in literature.

The right book at the right time?

I started the year 2021 with Sinead Gleeson’s anthology The Art of the Glimpse, and that brief sense of history which characterises the new year stretched out into the year’s first months as I worked through this tome which redresses the Irish short story canon.

A book that makes you laugh?

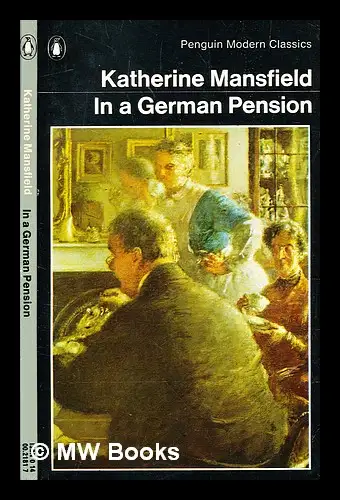

I was reading Katherine Mansfield’s first collection, In a German Pension, in the library recently and disturbed the peace with my outbursts. I think that we use humour to make our lives palatable, so when you find it in a book, the character that made you laugh often has some deeper tragedy or fear which their humour helps them float above. In my own writing comedy and tragedy often merge completely.

A book you associate with a particular life event?

I had a knee operation last year and read the Norwegian author Marit Eikemo’s collection Hardanger in my hospital bed: subtly surprising and subversive stories, clear enough to sear through the fog of painkillers. (Someone should translate it.)

I also read Tarjei Vesaas’ The House in the Dark, where everyone is locked up in a country-sized house that represents Norway during WWII occupation. This was a more troubling read, given my pain and immobility at the time, but worth it: a powerful exploration of what it is to be a hero or a coward. He gives a great depiction of the heaviness of war. Of course it’s completely sexist, and so it fails to a certain extent in the same way as Albert Camus’s The Plague. Both books attempt to give a cross-section of society by choosing an array of male perspectives. As such they were always going to fall short of the complete picture they were trying to construct.

One of your own books you would save?

If it was the last copy in the world, I would save Habitat, but if the fire in this question was less a Fahrenheit 451 scenario (where books are forbidden and burned on discovery) and more a current day domestic tragedy, I would save something half-finished and unpublished, something that still partially exists in notebooks, perhaps a story I’m writing about a jumble sale.

It started it with a certain rhythm in my mind and a sense of tumult that parents of young children can experience, and I’m still trying to bring the right kind of troubling music to the page.

A book you are reading now?

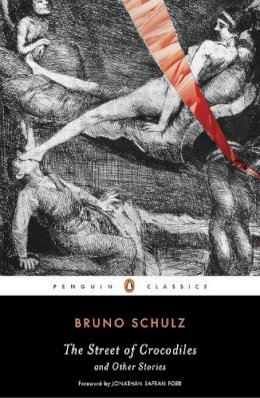

I’m enjoying a collection of Bruno Schultz stories, The Street of Crocodiles. His depictions of childhood are full of gravity and mesmerising details, language contorting to previously impossible forms.

A book you’d leave to burn?

I would happily leave The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo to the flames, except I already seem to have got rid of it. There was a repeated mention of something like “that difficult experience she didn’t want to think about” that riled me. This was the book that taught me to abandon a book if I’m not warming to it.

You can save one non-book item: what is it?

My son’s first family portrait. He put us standing on various edges of the page.