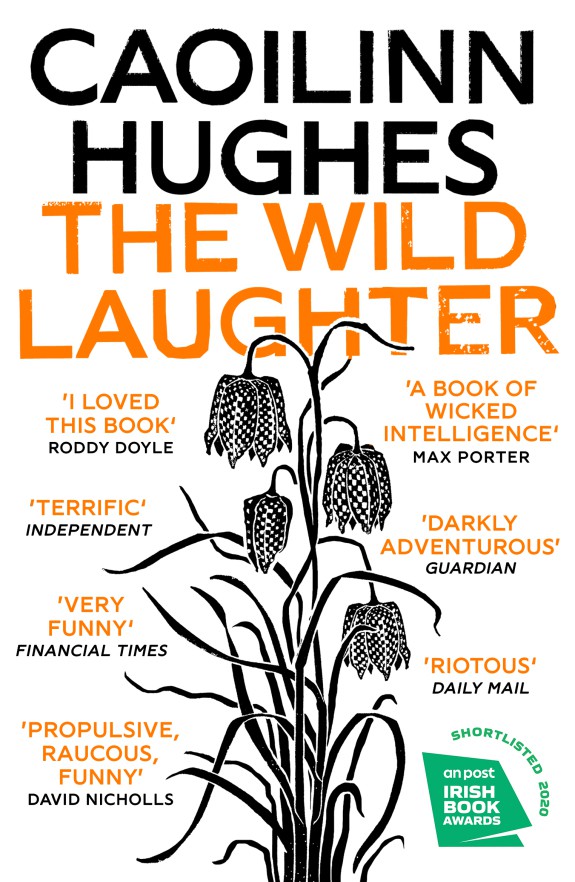

Mary McCarthy speaks to Caoilinn Hughes about her latest book The Wild Laughter

THIS LITERARY LIFE

The plot of Caoilinn Hughes new book The Wild Laughter may put some readers off—assisted dying and financial ruin may be themes readers want to avoid right now—but while some parts are very sad and thought provoking mainly it is a comedic book.

Her second novel sets up a bleak family tale, but the winning narrator, the 25-year-old Doharty, or ‘Hart’, and his stream of wisecracking expertly turns it on its head. ‘I laughed a lot writing it’, Caoilinn said. Hart is someone you can’t but like, who is left driving the tractor and doing all the work while his older brother, Cormac, organises loans for new farm machinery and pockets the profits. Hart comes across as slightly socially stunted but also so perceptive about how ridiculous humans can be—especially when blinded by the promises of the Celtic Tiger. A priest later tells him his ‘honesty is his biggest strength and his biggest weakness’. He did not have much of a childhood but he is going to miss his father, or ‘the Chief’ as his sons call him, who has slogged all his life on the farm not taking one day of luxury off, only in his last years to be crippled by debt from ill-advised property investments in Bulgaria. He has horrific lung cancer and is in a lot of pain so has asked his sons to help him die but first the family goes to Connemara for one last trip. An actress called Dolly, whom Cormac has pitched up with, hitches a ride, and that car journey is one of the many comedy masterstrokes.

Hart ends up in a sort of relationship with Dolly and seems to like her a lot, though her theatrical antics mean ‘she is a curse to be around. I was halfway to rigor mortis myself’. He makes quite a few observations that would make any woman nervous: ‘The mole on her chest sprouted a hair. I nearly went to pluck it.’ The meandering story that unfolds has echoes of the case of Marie Fleming, who in 2013 unsuccessfully petitioned the supreme court to change the ban on assisted suicide, and this might put off readers who don’t want to be dragged into a downer but, while it does tug at the heart in places, it is one-fifth wounding to four-fifths hilarious.

If you can, go for the audio book narrated by Chris Dowd—funnily enough, also from Roscommon where it is set—because his naturalistic delivery of Hart’s unfiltered thoughts are pitch perfect and a pure pleasure to listen to.

Caoilinn’s talent has been recognised, but once The Wild Laughter hits the book club circuit (and it is perfect for this) this will be what makes her name. Her first novel in 2018, The Orchid & the Wasp, won a bunch of awards, but it was poetry she first wrote, with her collection Gathering Evidence winning the Irish Times Strong/Shine Award in 2014. Her short fiction has won many accolades, including the Moth International Short Story Prize in 2018.

Caoilinn has gone after a serious theme here but her writing tells you she does not take herself or life that seriously. She lists Beckett as an influence, and his existentialist, droll stamp is everywhere in The Wild Laughter. After many years in New Zealand and later the Netherlands studying and working in universities she is now moving back to Ireland.

Trinity just announced Caoilinn is their writer Fellow for 2021 and her new colleagues and students will learn a lot and are very lucky to get her.

Where do you write?

At a desk in whatever house I’m in—it can be a kitchen table, but I prefer to be able to close myself behind a door. I can write in cafés too, if I’m deep into a story or novel, but I tend to listen to brown noise soundtracks or café noise soundtracks while in cafés! They’re beautifully calibrated so that you can’t tune into any conversations or hear anyone masticating. Although … 2020 has made me feel nostalgic about the sound of strangers chewing. So maybe I won’t want the soundtrack balm in the future.

What authors influenced you?

It’s so tricky to acknowledge influences when the truth would include the authors of every nursery rhyme and poem and story and play and novel and film and song and hymn and advertising slogan I’ve encountered! So I’ll limit it to possible influences on The Wild Laughter.This novel is heavily influenced by playwrights including Sean O’Casey, J.M. Synge, Marina Carr, Tom Murphy, Oscar Wilde, Stewart Parker, Brecht, Beckett etc., then novelists/story writers like John McGahern, Virginia Woolf, Doris Lessing, James Baldwin, Kafka, Keri Hulme, Janet Frame, Toni Morrison, Zadie Smith, Clarine Lispecktor, Iris Murdoch, Camus, Chekhov, Michael Bulgakov, Flann O’Brien, Dorothy Parker, Kurt Vonnegut and the contemporary authors I was reading while writing it.

What do you do if you get writer’s block?

I stop writing and go back into what I’ve written to find the erroneous decision or manipulated moment that is preventing all the bricks laid after it from sitting flush. For me, the problem always lies in what’s gone before, not what’s to come.

What advice would you give to budding authors?

Don’t rush.

Do you ever want to pack it all in and do something else?

Only when I think about how a writer forfeits so much of their privacy over the years, if they keep publishing books. I don’t love this aspect of the writer’s life at all. I like to stay in the background, but that’s almost impossible to do. If only there were a thousand examples of Elena Ferrante’s shadow stance. But there aren’t even a dozen.

What did you do after school?

I went to art school for a year—the foundation before a degree in fine art. I didn’t want to become an artist (I enjoyed being bad at it so much that I had little mind to improve) but I hadn’t gotten into university, so that year was a way to move into a creative transitional zone. I worked in a record shop. Then I moved to Northern Ireland to study at Queen’s University, where I did my BA and MA degrees. (They let me in despite my B minus in English, for which I am eternally indebted.) The MA was in Twentieth-Century Irish Theatre and Culture. Then I moved to New Zealand for seven years, where I got a corporate job to save money, then did a Ph.D in English Literature and started writing fiction in earnest. Then I moved to the Netherlands for a three-year university gig sevenish years ago and now it’s 2020 and the narrative has stopped playing at linearity!

When did you decide to give writing a go?

I don’t ever remember deciding to give it a go. I’ve just always done it. I never completed or shaped things as a child, so that wasn’t really writing as I understand it now. It was gestural. I have no recollection of ever being asked to write poems or stories for school, which—in a way—was helpful, because that would have made it a conscious act. It would have made it feel contrived and fraudulent, for me. I do remember the difference, though, between writing stuff and writing something that I felt to be real. I was undisciplined and impatient as a teenager, except about sucking tea through Penguin bars: that I did with precision and rigour. Only in my mid-20s did I start spending enough time writing to accumulate those 0.01 percentages into sentences.

Can you give other writers three tips?

Is ‘other writers’ different to ‘budding authors’? If so, I would never give advice to my peers! I’ll take their advice possibly, but I would only give out curse-filled encouragements.

Did you enjoy writing The Wild Laughter? How did it compare to writing your earlier novel Orchid & the Wasp?

They are very different books, structurally, tonally and stylistically, so perhaps it’s no surprise that the writing of the two novels differed dramatically. Orchid & the Wasp was terrifying to write and it took years. It’s a very unconventional book that appears to squinted eyes to be a coming-of-age, rags-to-riches sort of narrative. (When people see a young female protagonist, they often assume coming-of-age; that the story will prompt the young woman to discover her inner strength that will help her overcome various obstacles.) Instead, it’s a picaresque novel following a woman’s career of sorts, or the progression of her ideas over time, as she tests them out upon society—some of those ideas are cynical, some are sad, some are dubious and contradictory. Picaresque novels with female leads are few and far between—especially if you leave out ones involving the pursuit of marriage, like Emma and Vanity Fair. Novels with female leads who don’t have hearts of gold (who aren’t heroines), who aren’t sociopaths either, and whose narratives don’t revolve around men are very rare. On top of being that rare species, it’s a novel in which most characters appear only once or twice; it’s a novel told in scenes, with no explanatory summary; and it spans a decade. What’s more, I wanted to refrain from using death in the plot of this novel: I didn’t want any characters introduced to die. As I was writing the book, I knew that all this would make it a very big ask of a reader. I had to really believe in the reader to write that book.

The Wild Laughter is a first-person narrative and its characters have very strong senses of humour, so I wasn’t working against the grain as overtly with this novel. This one cajoles the reader a bit more than Orchid. There are innovations with story and in the way the novel plays into and against stereotypes (as well as the stereotypical Irish story) … but the reader is ideally in deep before those tugs on the carpet are felt. If Hart wins them over, they might mistake them as tugs on the gut. It was less terrifying to write because the narrative voice has this luring, hand-on-the-shoulder, hand-on-the-heart quality, in contrast to Gael’s/Orchid’s irony … but there are always unwise challenges! For example, the novel’s plot centres around something laughably grim! Its elevator pitch would make you want to jump down the elevator shaft. Let it never be said that I make things easy for myself! But I laughed a lot writing both books—there are characters in both that I’m glad to have known. They tortured me while being bloody good company. And the characters I’m working on now feel the pressure! I have to hope it doesn’t break them, or me!

***

Mary McCarthy: This Literary Life

Mary McCarthy is a freelance journalist writing for a number of publications. She is an avid reader and an iron-willed book club administrator.

@maryknowsbees