“We were all on our desert islands…but the photographs acted like the ship coming in.”

—photographer Alan MacWeeney and artist Pesya Altman talk to Bel Kelly, about how My Dublin 1963 // My Dubliners 2020 (Lilliput Press) came together during the hardest year of their lives

by Bel Kelly

In the spring of 2020, the world shut down.

Schools and jobs went virtual, social events were cancelled, and the future was suddenly more uncertain than ever before. Confined to a house in Sag Harbour, New York, photographer Alen MacWeeney and artist Pesya Altman came upon the idea for a poignant and reflective photo book like no other.

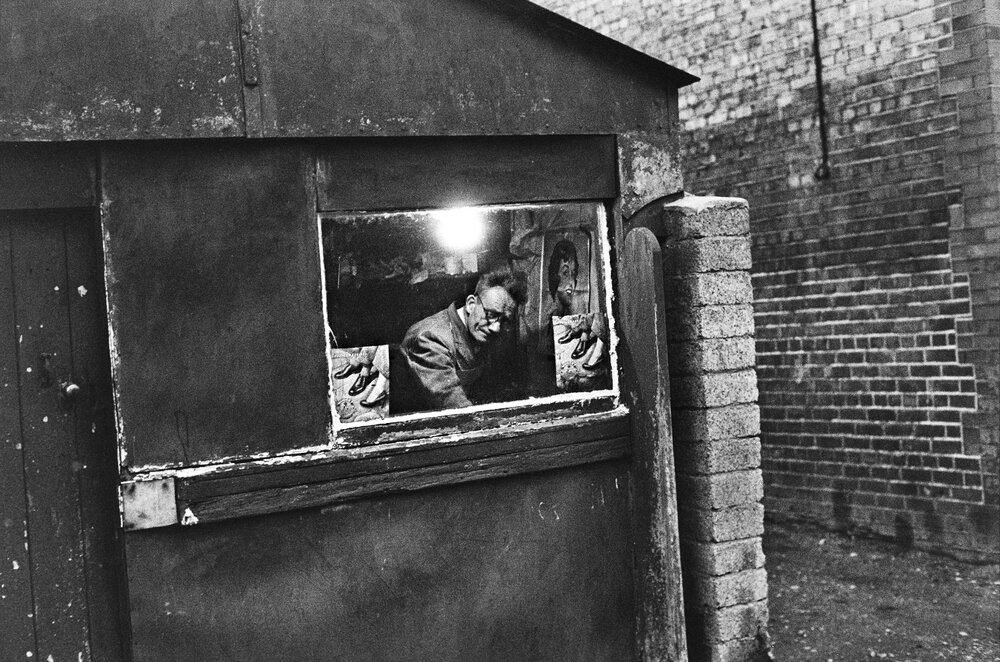

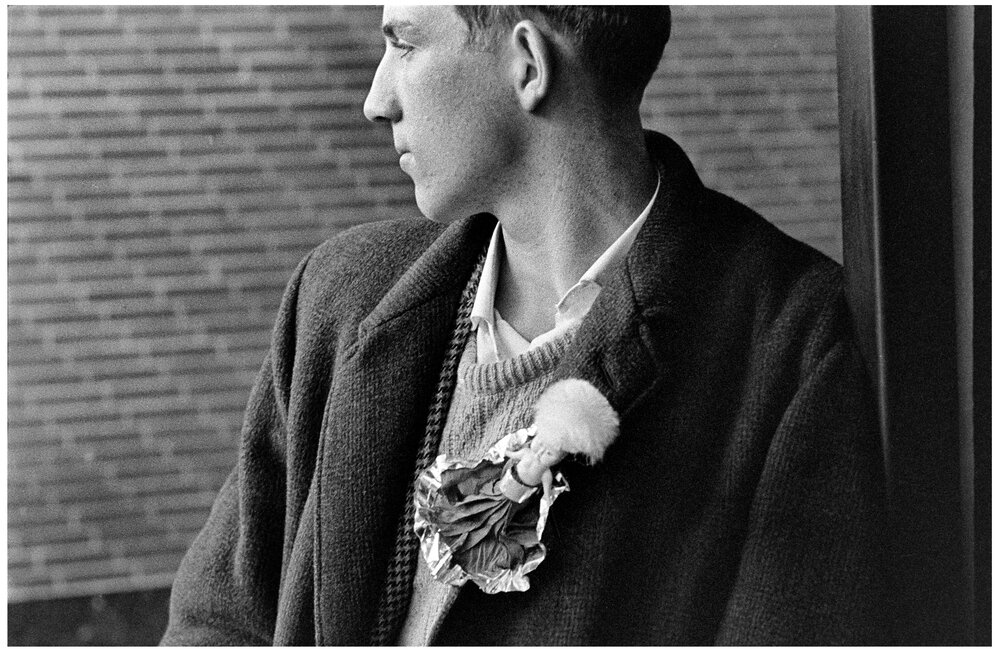

Back in 1963, MacWeeney took photos all around Dublin. They were candid and beautifully ordinary, depicting here a group of lads on the street, here a bridge, here a mother pushing a stroller bundled up against the weather. However, MacWeeney says, “Pesya’s really the architect of the book.”

“I think when Sean closed the auld place, part of the village died, always look when walking through the lane…”

Memory

A Manhattan high school reached out to Altman during lockdown in the fall of 2020 asking her to teach a class there virtually. The subject? Memory. With her students, Altman began exploring the relationship between photographs and memory.

Then, she had an idea of how she could explore long term memory by engaging with MacWeeney’s photos—something she could bring to her students to discuss.

“I will post those photos to a group of Dubliners and see what they remember from their childhood,” Altman says, recalling the moment the idea sprang to mind.

She proceeded to do exactly that. In a Facebook group called Dublin Down Memory Lane, in which members could post any pre-2000 photo taken in Dublin, Altman posted one of MacWeeney’s photographs.

“My great grandad helped save someone from there.”

Responses from Dubliners

That first post gained hundreds of comments from Dubliners in the group. They recalled memories, offered up facts, began conversations. “Because people were in lockdown,” MacWeeney says, “they looked at the photographs with much more attention and detail.”

Altman kept posting them, fascinated by the response, and charmed by the attention to detail and the breadth of emotion in the comments. Soon, she was posting two, sometimes three photographs a day, and receiving up to 1,600 comments on each post.

“The photographs became the kind of lynchpin of emotions and thoughts of the people,” MacWeeney says.

It was then that he and Altman realised they had a book. The visuals would be, of course, MacWeeney’s photographs. The text? The countless comments from Dubliners building narratives around each photo. “[The book] couldn’t have been written by one person, because no one has that breadth of curiosity, interest, education, non-education, anger, emotions,” MacWeeney says.

“I wonder if there are many of these dolls left. Our neighbour made and sold hats flags and suppose dolls for the matches. All the family helped and also went out to sell. A hard working family.”

Expressive

Altman was equally taken by comments, and specifically by the locality of them:

“I have no connection to Dublin in the past. The first time that I came to Dublin was for the book. But I still am fascinated by the way that Dubliners express themselves… I believe that it’s very Irish… [that response] cannot happen in another place on the planet.”

A lover of Irish literature, particularly Samuel Beckett, Altman sees his seminal play Waiting for Godot in the book, and in life during the pandemic in general. “I feel like we are all waiting for Godot now in some ways,” she says.

Sense of community

Living through lockdown not only influenced the direction of the book, the pair agrees, but completely shaped the project from start to finish.

Both the uncertainty of the pandemic but also the sudden isolation and lack of community were huge contributing factors to the photographs getting the response they did.

“If we don’t know anything about the future,” Altman says, “at least we can hold the past, and cherish our life in the past and the sense of a community and be part of something bigger.”

“We were all on our desert islands,” MacWeeney agrees, “but the photographs acted like the ship coming in.”

Ultimately, the book is a celebration of this—community, identity, memory: connection, even in isolation. “It’s a text that couldn’t be conceived,” MacWeeney says, “it had to be found. And Pesya found it.”