Dangerous Ambition: The Making of Éamon de Valera|Colum Kenny|Eastwood Books

A Child Entirely Apart—an extract from Dangerous Ambition: The Making of Éamon de Valera

by Colum Kenny

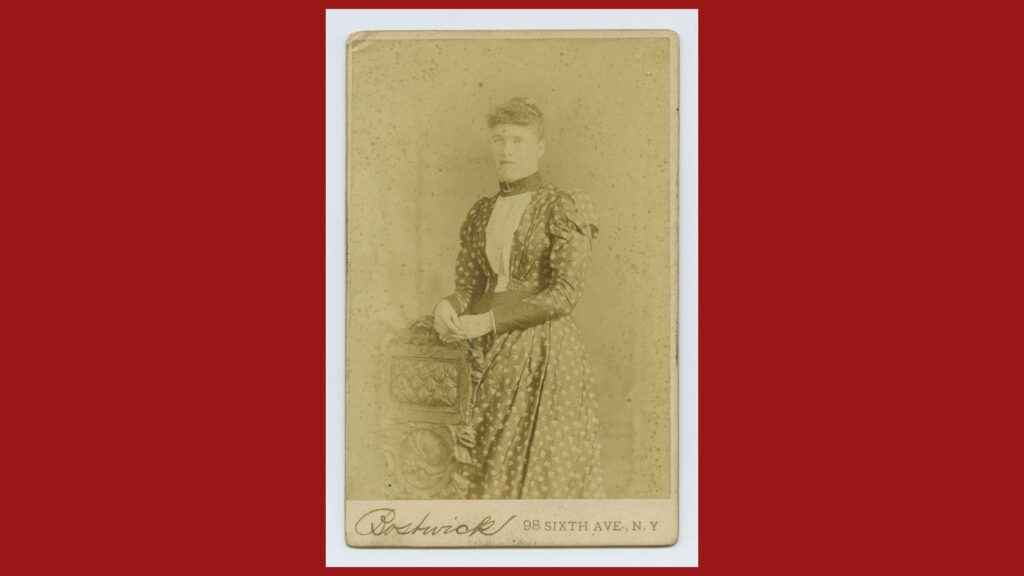

In 1885 De Valera’s mother sent him to be reared by members of her family in Co. Limerick when he was not yet aged three. His ‘Spanish’ father was long gone and she could not cope with rearing him in New York City where he had been born:

The appearance of an infant from Manhattan in Bruree, adorned with curly locks and wearing a velvet suit, impressed itself on the memory of the local station-master who reportedly described it as ‘pure Lord Fauntleroy, complete to lace collar’. Schoolboys, unaccustomed to sartorial elegance, were most unlikely to let it pass.

However, although Eddie (as Éamon de Valera was then known) reportedly brought with him to Ireland this suit consisting of jacket and breeches, he was not always clothed in trousers in Bruree. Many young boys and girls then dressed in a similar style of clothing, this being a dress or petticoat such as later became exclusively associated with girls. When Eddie’s grandmother took him with her into the village of Bruree in 1886, to see a meeting called to support a boycott of a local landlord,

I was in petticoats and I had long hair – my grandmother was rather proud, if I might put it that way, of my hair. It was a golden colour, I believe! She wanted me to keep on wearing it. My uncle on the other hand, had more regard for my feelings in the matter with other boys and he wanted to cut it off.

Frank Gallagher, his friend and admirer, wrote of de Valera’s origins that ‘the mixture of races produced a child entirely apart’. Eddie might not have stood out as very exceptional in Manhattan but he was certainly notable around Bruree. Another pupil at this primary school, who later became a professor of classics at Fordham University, said that because of Eddie’s ‘olive complexion’ and surname the boys believed that he ‘was a descendant of some Spaniard wrecked in the Spanish armada’. Yet while de Valera would recall how a teacher found it difficult to spell his name, if there were any pointed racial insults by other boys these appear to have gone unrecorded. Asked by a radio reporter in 1965 if he was made to feel at home around Bruree, de Valera replied, ‘The curious thing when I look back is I seemed to have the entrance to every house in the neighbourhood. I knew them and would walk in … in any of the houses on my routes, that is around by Howardstown and so on.’ Were other young neighbours not likewise welcome? Was his reception ‘curious’ perhaps precisely because he felt, or indeed was, ‘a child entirely apart’?

Eddie might not have stood out as very exceptional in Manhattan but he was certainly notable around Bruree

Eddie passed much of his time in Bruree on his own. He often had to spend all of Saturday out minding cows. As he got older he combined this with reading. Books were an escape, and an encouragement. Robinson Crusoe, a favourite of his, is the story of a man surviving alone on a deserted island. For a long time Eddie saw no chance of getting away from Bruree and getting on. In the 1930s he told Dorothy Macardle:

One thing I had when I was a child that I liked playing with alone: I had no one to play with. I was alone a good deal. In the river I had a little island, and I used to shape it and make plans about it. This was Ireland and I was the ruler of it … And yet, though I dreamed a great deal, I had no ambitions or expectations. I had nothing but the spade. I remember a boy who lived next us; he was older than I, and he was going to be a draper’s assistant. I thought that was a big world from which I was forever shut out. To be a labourer was what was before me.

His friend Frank Gallagher was to remark that ‘a surge of envy swept that young American-Irish heart, clearly felt more than fifty years later’, as de Valera recalled for him the same moment:’ De Valera had thought about why people left the land and moved into cities. It was not just the lack of amenities. He believed there was some deeper urge to go away and get into a place busier and more bustling. He may have had a buried memory of Manhattan that excited him.

Eddie’s son Terry would one day paint a nostalgic picture of Éamon de Valera as ‘he reminisced fondly of his early times with his uncle and other relations in Bruree, Co. Limerick and spoke with affection of the little house which had tender memories for him.’ But Eddie was far from satisfied in Bruree. He thought that one option for him was to go to America. This is clear from a letter he wrote to his beloved Aunt Annie, who had cared for him when he first came to Bruree before herself emigrating. He opened a channel of communication with her when she went that appears to have bypassed his uncle’s supervision. Eddie’s grandmother (Annie’s mother) had died the previous year and he was now living alone with Uncle Pat. On 2 March 1896 he told Annie explicitly he was not content in Co. Limerick, that he had nobody to be with there and would much rather be in America. He pressed his ‘dear aunt’ to persuade his mother to send for him: ‘It would not be a bad plan if Mamma was writing to Uncle to say to send me over with someone that was going soon, and perhaps he might let me go.

But Eddie was far from satisfied in Bruree. He thought that one option for him was to go to America

Eddie liked to linger near Bruree on the hill of Knockmore, or the hill of Knockfenora and then by the brook. It cleared his head doing so. There was a very nice hazel tree, where you could get nuts in autumn. It was on the hill of Knockfenora that he slowly read through Abbott’s big biography of Napoleon. That was a man who made his own way in the world. Napoleon Bonaparte forged his own destiny. And Eddie intended to forge his.

This is an edited extract from Dangerous Ambition: The Making of Éamon de Valera, by Colum Kenny, published by Eastwood Books.

Dr Colum Kenny is a barrister, journalist and historian who has written widely for the media. Formerly a presenter and reporter with RTÉ, he served on the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland and is a professor emeritus of Dublin City University. Born on Eccles Street, Dublin, he is married with three sons. His books have included histories of Kenmare and Kilmainham, biographies of Arthur Griffith and Tristram Kennedy MP, accounts of the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations of 1921 and the Irish Civil War, a study of a family of Irish immigrants in America, and a monograph on King’s Inns, Dublin. In 2018 he was awarded the Irish Legal History Society’s Gold Medal, and has also received the medal of the Old Dublin Society. He is the author of two overviews of Ireland in the period 1973–2020, and sees Éamon de Valera as a key to our understanding of contemporary Irish affairs.