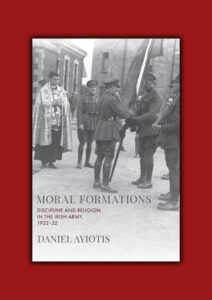

Daniel Ayiotis explores the relationship between discipline, religion and the Army in Moral Formations—read an extract here

Moral Formations: Discipline and Religion in the Irish Army, 1922–32 is a comprehensive exploration of the transformation of the Irish Army from the Civil War to the Eucharistic Congress. This vital work by Daniel Ayiotis explores the intricate relationship between discipline, religion and the Army, shedding light on the challenges faced and the values that were required of soldiers, from manliness and clean living to a chivalrous spirit and a degree of religious fervour.

This examination raises important questions about the role of religion in shaping the behaviour and actions of the Army and the influence of religious instruction on young soldiers. It also acknowledges the role of the Irish Army as a government institution and the values that were instilled during its early years of formation.

An extract from Moral Formations, by Daniel Ayiotis (Wordwell)

CHAPTER 4: BOYS LED ASTRAY

Religion was not only a fundamental component of Free State identity during the Civil War. The anti-Treaty side also had a strong spiritual ethos. This is particularly evident in the vivid language around hunger strikes, but also more generally in their self-perception as ‘guardians of the soul’ or ‘keepers of the flame’ of the Irish nation. Not all priests supported this ‘young Army of a Christian state’. Some were of a more subversive disposition. The Adjutant General and the Archbishop of Dublin had been resolute, in establishing the Chaplaincy Service, that the nominated priests be politically and socially sympathetic to the Free State, Byrne being well aware that some of his priests were of a decidedly anti-Treaty disposition.

Not all priests supported this ‘young Army of a Christian state’. Some were of a more subversive disposition.

One such subversive priest was Fr Joseph Smith of Mount Argus, Dublin. On 15 December 1922, the Director of Intelligence, Commandant General Diarmuid O’Hegarty, wrote to Mulcahy recommending that ‘it would be extremely desirable that Fr Joseph’s case should be brought to the notice of the Archbishop of Dublin’. It is a small detail but one illustrative of the social hierarchy of the time that O’Hegarty recommended that the best channel through which this could be done was through the President of the Executive Council of Dáil Éireann, the most senior politician in the country

O’Hegarty had received the information on Fr Smith from a Seamus O’Dwyer, who informed him that:

The Reverend Father Joseph of Mount Argus announced from the altar at eight Mass on Sunday last the 10th [of December] that Seán Hales had been murdered by CID [Criminal Investigation Department] men and that the ‘slave state’ had murdered four republican prisoners. This man makes use of the altar weekly to incite a very impressionable congregation. I think quiet representation to His Grace of Dublin would be better than any public attentions to this mad man and would be a much severer strain on him as well.

CLEAN-LIVING IRISHMEN AND DECENT, RESPECTABLE GIRLS

The twin vices of drink and venereal disease cropped up again in December of 1924, when the Adjutant General corresponded with the Minister for Defence (Peter Hughes, who had replaced the interim minister, Cosgrave, the previous month) about the Minister’s previously expressed opinion on the need to improve welfare conditions for soldiers. Mac Neill noted that, while there had been some specific examples of positive efforts in relation to soldiers’ welfare, the general condition was such that ‘the general welfare and comfort of the soldier off duty has been scandalously neglected’. When a private soldier was dismissed from parade in the evening, there were generally two sources of amusement open to him, namely, ‘loose women or public houses and shebeens’. The natural consequence of this was, of course, the spread of venereal disease.

even with the best will, proactive officers were ham strung without the money to bring their will to bear

As for the blame, Mac Neill laid this at the feet of both junior officers, whom he opined had neither realised nor bothered with the fact that the welfare of their men was their responsibility, and the state itself, which had ‘not recognised any financial liability in such matters’ so even with the best will, proactive officers were ham strung without the money to bring their will to bear.

It was from this impetus that Mac Neill initiated the Soldiers’ Welfare Scheme. In many ways it was predictable, but perhaps it is more accurate to say that the solutions were well known but had never been properly implemented. Mac Neill recommended that the welfare of troops be rigorously inculcated in officers and requested the necessary funding from the Minister. A wide range of sporting activities were naturally included, given the physicality and demographic of the men concerned. In relation to wintertime amusements, the matter of dances came in for particular attention, as a potential moral pitfall. The matter was discussed at length, and ‘it was decided that large Battalion or similar dances were out of the question, but that short Company dances could receive consideration’.

In relation to wintertime amusements, the matter of dances came in for particular attention, as a potential moral pitfall

Keeping these dances parochial and among relatively small, closely frequented groups of soldiers, ‘would at once let the soldier – and the country – see that he is recognised as a decent, clean-living Irishman, who can be depended on not to abuse a privilege when he gets one’ and would ‘encourage him to seek the company of decent, respectable girls, whom he need not be ashamed to “show off” before his comrades, Officers and Chaplains’.