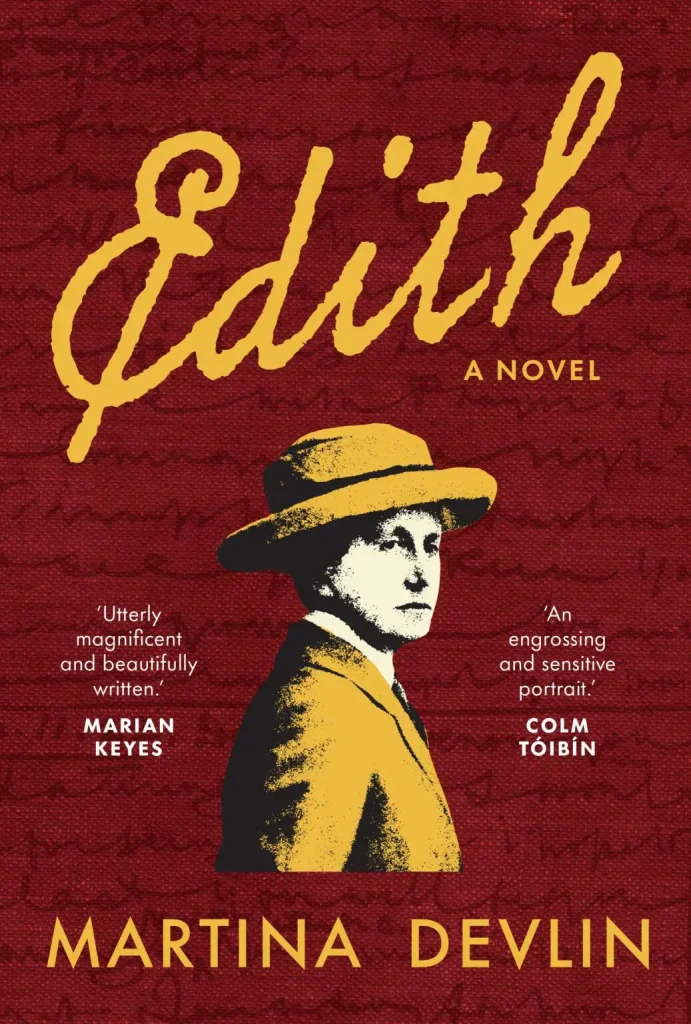

Edith|Martina Devlin|Lilliput Press|ISBN:978 1 84351 8303|O’Mahony’s €16

“Martina Devlin has created a wonderfully enjoyable snapshot of a pivotal time in Irish history.”—Susan McKeever reads Edith, by Martina Devlin.

by Susan McKeever

There’s a lot to unpack in this saga from Martina Devlin, based on the life of Edith Somerville, a writer who, with her cousin and dear friend Violet Martin, co-wrote a series of bestselling books.

Together known as ‘Somerville and Ross’, their most profitable books formed trilogy of stories about an Irish R.M. (Resident Magistrate), which helped pay for a host of things including a new roof, glasshouse, and paved avenue for their family seat. It’s pacey from the start, with twists and turns and multiple plot lines.

Edith Somerville

Edith Somerville is ‘a youthful sixty-three’ and lives in Drishane, the ‘big house’ in Castletownshend, West Cork with her older brother Cameron, known affectionately as ‘Chimp’ – in return he calls her ‘Peg’.

We first encounter Edith bustling around Skibbereen doing errands and from the start her character is clearly drawn – she’s a plucky, intelligent feminist who doesn’t suffer fools and loves her big house with a passion.

But the setting of 1921 is a tricky time in history for members of the Ascendancy; the Irish have had enough of British rule and the War of Independence is on the cusp of turning into a civil war.

The IRA flying columns are running wild through the countryside of West Cork, looting and burning out big houses to fund their cause.

Bubble of existence

Against this backdrop, Edith and Cameron continue to maintain their privileged lifestyle. A three-course luncheon, taken in the dining room, is made by the cook and announced by a gong. Stables of horses are managed by a groom; a horse and trap is produced at the front door for jaunts to the village. Fires are lit each morning by the housemaid and tea is brought on a tray to each of the siblings on waking.

In this bubble of an existence, upper-class standards and behaviours are maintained to the letter.

A ludicrous example of this is when ‘breeding prevents Edith from propping a book against the salt cellar’ when she dines alone.

Financial embarrassment

But finances are a problem in this folly of a lifestyle, flagged to Edith by the embarrassment of unpaid butcher’s bills in Skibbereen. Cameron announces, ‘The tin it costs to keep the house running beggars belief.’

Edith’s writing partner is six years dead and the profit from the books has dried up, although Edith still connects with ‘Martin’ from beyond the grave via ‘automatic writing’ sessions. The only thing for it, she decides, is to bring the R.M. stories to life for the stage.

Rollercoaster

Thus a tableau is established for a bit of a rollercoaster in terms of plot and it is impressive how much Devlin squeezes in. IRA soldiers arrive in the night, rapping on the door ‘in the name of the Irish Republic’ and leaving an itemised list of the goods they purloined, including jewellery, a horse, and ‘one chicken cooked & various foodstuffs’.

A cast of characters emerges, including Edith’s friend Ethyl Smyth – a hoot of a woman with a transparent girl crush on Edith.

While we’re on girl crushes, Edith seems to have had same on her erstwhile pen-mate, Martin, but I’m assured this was nothing more than pure affection and respect.

George Bernard Shaw

There is a hilarious interchange with George Bernard Shaw, Edith’s cousin Charlotte’s husband in Hertfordshire; Devlin must have had a good deal of fun penning these droll imagined conversations.

‘GBS’ as Charlotte calls him, treats Edith to a visit to his revolving writing hut in the garden – ‘a simple but effective health measure’ that he spins around to follow the sun.

In London, Edith meets with her literary agent Mr Pinker, and then with manager of the Lyric – whose splendidly apt name is Nigel Playfair.

Thriller-like feel

The story assumes an almost thriller-like feel during a life-or-death encounter Edith has in a fog-bound London, complete with faux cockney accents assumed by covert IRA spies.

In her first novel, Martina Devlin has created a wonderfully enjoyable snapshot of a pivotal time in Irish history – immersive and entertaining, with the attention to detail that only comes with meticulous research.

I did find some of the passages occasionally sank into a rather corny, simpering tone, which let the writing down at times – most marked when referring to the beloved fox terrier, Dooley. It was also hard to read the condescending references to the ‘natives’ that pepper the book: ‘The savages are running wild … They need to be culled’.

Woman of the people

Edith positions herself as a woman of the people, always countering with Black-and-Tan atrocities when the IRA violence comes up in her circle, and cherishing the independence her two servants retain despite the economic relationship.

But at the end, I have to agree with GBS’s pronouncement about the big house versus native cottage dynamic: ‘The houses have been complicit in the subjugation of the people. They symbolise division.’

And at this point in time, the likes of Edith have become a dying breed; a ‘descendancy’ incarcerated within their demesne walls.

Susan McKeever is an editor, writer and ghostwriter for several Irish and international publishers and authors. She works from her home in the red-brick heart of Dublin’s Portobello. @MckeeverSusan, susanmckeever.biz