Beyond Sorrow, by Karen Beatty

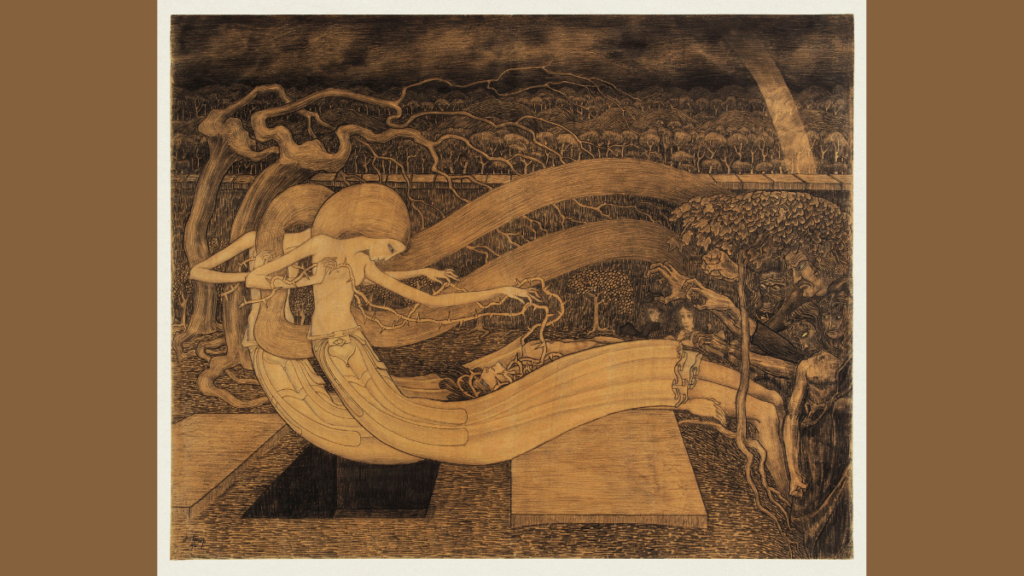

Watching our Mama die is so wrenching that I can only believe that grieving will be a relief. She is fighting for her life while we’re just trying to carry on with ours.

Mama is not ready to die but not able to live. Helping someone die is different from helping someone live. Dying seems more like birthing: you can plan for it all you want—then you deal with what happens.

Which of our mother’s maladies are the doctors actually treating: the skin cancer? her high blood pressure? the congestive heart failure? her mental deterioration? Each doctor that drops by touts his own wares.

Mama has been hospitalized several times before, but it seems different this time. I can sense the buzzards circling.

She has too much unfinished business to allow herself to just let go.

She won’t finish that business.

When she was dismissed from the nursing home for unruly conduct, she spat at the nurse and refused to state her name at discharge. My brothers apologized to the staff and glanced at each other and smiled. Mama’s evil twin (or is it her authentic self?) is back.

Doctors warned that Mama would not be herself when she became increasingly ill. Sadly, under anti-psychotic medication, which she soon refused, was the only time she was amenable and interacting appropriately.

Now she is unconscious with a ventilator crammed down her throat, spittle accumulating around the edges. Her body is small and cold. Such indignity. I look at the wires and tubes and think, “People have pulled the plug on dying loved ones. Yeah, I could do that. I wish she had died in her sleep last night. I wonder which one is the plug?”

“She’ll come out of it,” a pitying, nurse says and shows me the papers for a living will directive. Later we ask Mama if she will sign. She won’t.

She comes out of the crisis, but she isn’t the same person who went under. Her tongue is stretched out grotesquely. Her body looks frighteningly frail, and over her eyes, like a pall, is a milky film.

My seven siblings and I each once nestled inside that body.

I massage her feet, something I would never have done before this.

That’s our Mama there.

This week she fought the doctors so fiercely that we had to witness her hands tied down and bleeding from the wrists.

They shoot horses, don’t they? Torture is an international war crime. They had to destroy the village in order to save it.

At last she lets go.

Rejoice, brothers and sisters. And weep.

Karen Beatty: I think of life as a river, coming and going, surging and flowing. Reared in Eastern Kentucky near the temperamental Licking River, I served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in the 1960s, immersing myself in the cultures along the mighty Mekong River, bordering Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. I finally settled in Greenwich Village, between the Hudson River and the East River, on the Isle of Manhattan, where I teach police officers, firefighters, immigrants, and Veterans. I have been awarded first prize for an essay in the New England Writer’s Network and my short stories and essays appear in Eureka Literary Magazine, Writers’ Post Journal, and Snowy Egret.