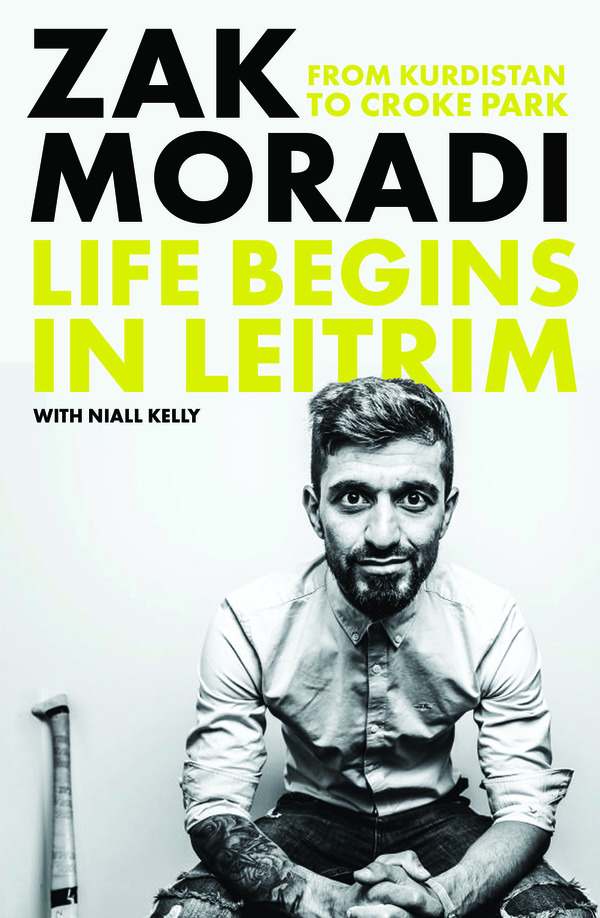

Life Begins in Leitrim: From Kurdistan to Croke Park|Zak Moradi|Gill Books|€22.99

From Kurdistan to Croke Park—Zak Moradi talks to Fiona Murphy about his incredible journey

by Fiona Murphy

When eleven-year-old Zak Moradi landed in Leitrim in 2003 from an Iraqi refugee camp with little English, I imagine it was a similar feeling to standing at a great precipice, a whole new world, new culture, new community yawning ahead of you.

We’ve never been more aware of displacement, of opening up our homes and communities to those who need both. And Semaco “Zak” Moradi, a Kurdish, Irish hurler who plays as a left corner-forward for the Leitrim senior team, is a vision from the future: how the precipice can lead to a path of unimaginable adventure and success.

‘When I was younger, I didn’t think I’d be able to speak English like this. I didn’t think I’d become the person I was.’ Zak explained, painting a vision of that unsure young boy, who became the sports star now releasing his own memoir.

From understanding this world only through what his brother could translate for the family to becoming an integral part of Irish communities, Zak couldn’t have predicted his journey anymore than he could have known what to do when picking up a hurl for the first time.

‘Like every young person, you just don’t know what’s down the road. And that’s what sports can do and can change in you.’

Community in sport

Zak’s new memoir, Life Begins in Leitrim: From Kurdistan to Croke Park documents his journey from a refugee camp in Ramadi at the height of the Gulf War to Carrick-on-Shannon and all the way to Croke Park. But that journey and that recognition of community in sport started long before a hurl was placed in his eleven-year-old hands.

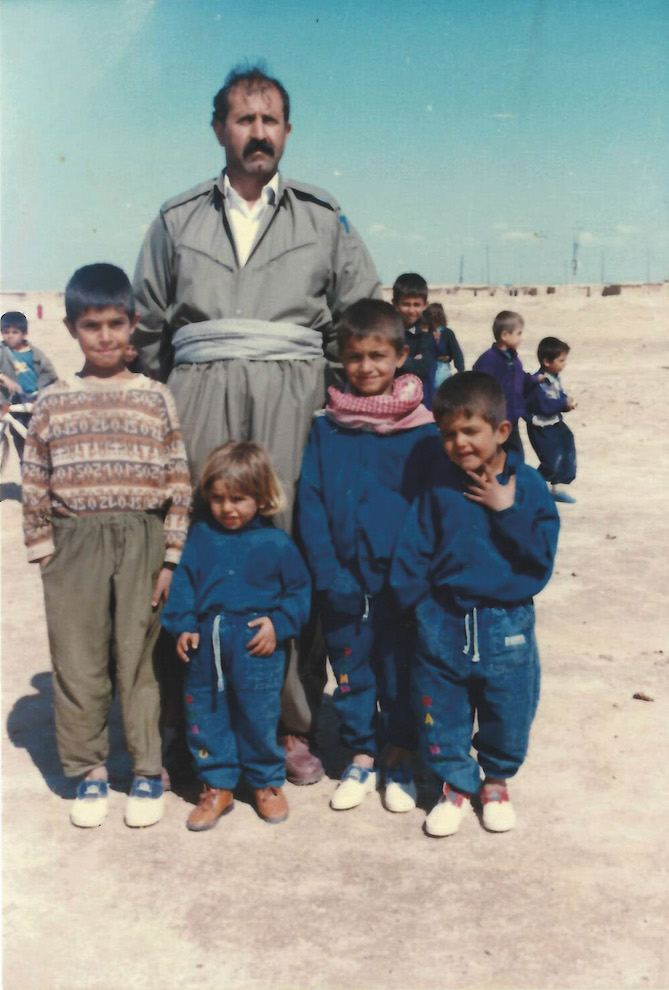

“When I’m looking back on that refugee camp, we had nothing to do. Hide and seek and one ball between twenty, thirty of us, and we’d play soccer, with our bare feet on the hard ground and stones. And our feet got used to it, you know, when you’re playing on it all the time, and the football kind of brought us all together in that refugee camp. And that shows what sport does.”

Standing out

That sense of community was found once again in the GAA when he arrived in Ireland, even if his background meant that he stood out on the pitch more than he ever had in the camp.

While the face of GAA is ever-changing and diversifying now, almost twenty years ago when he first arrived in Leitrim, Zak’s presence on the field was of interest, and not only for his talent.

“When I was younger, I just thought I was one of the lads playing hurling, Gaelic, I didn’t look at anything any different. I was the only tan lad playing, or brown lad, but I never thought of those things. But as I got older, I realized I was more noticeable on the pitch, and people were interested. Who is this lad, where is he from? But at the same time, if I’m playing the opposition and if he’s Chinese or if he’s black, I’d be like where’s he from? So I understand people’s situation.”

Inspiring story

This interest in his background and his life’s journey is perhaps what led to the realisation of this new book. And while trying his hand at writing instead of hurling may seem like a U-turn to some, Zak had often been told he had a book in him, even if he didn’t quite realise it at first.

“A book about what?” he joked, self-effacing, despite his inspiring story. “It kind of just happened. Sean Hayes from Gill was on Instagram about a year ago during Covid, and people said to me that there would be interest in ‘my story’. But I wouldn’t think of that, that I have a good ‘story’. It was just the way I was brought up.”

Emotional

With his family playing a huge role in his life, I wondered what they thought of their lives and journey to Ireland being portrayed in their brother and son’s memoir.

“They were delighted. I didn’t tell them until I got closer to finishing the book. I wanted to get to halfway and then to tell them. I was interviewing my mom, and I told her. And when you tell your mother then she tells all her sons and all her sisters. But when I told one of the lads in the club it spread like a fecking disease. Everybody on the hurling team was like ‘oh did ya hear Moradi has a book?’ You tell one person on the team and they tell their family and their friends… it’s as I always say, people are interested in new stories.”

Memoir writing can be a tricky business; sharing the past with readers can feel exposing, but perhaps a little therapeutic as well.

“It was emotional, trying to tell the story. When you’re trying to look back at what the family had to go through in that refugee camp and the other people as well…when you look back it was really a prison, because you weren’t really allowed outside our camp. And you’re always trying to be getting out of it.”

“We were in No Man’s Land,’ he explained. ‘The land does not belong to anybody. Living on a mucky ground and houses built out of mud. And I would call that no man’s land as well, because we were in a place where nobody cared about us. When my parents moved over in the eighties, before I was born, the whole place was caged, fences surrounded it. And over the ten years, people just got sick of it and they ripped all the fences apart.”

GAA a life-jacket

With the war in Ukraine weighing heavily on our minds, Zak reflects in the memoir on his own first culture-shock riddled months in Ireland. For him, the GAA was a lifejacket, something he feels is true no matter your walk of life.

“I think Gaelic is really a community thing. When you become part of that, you’re part of it for the rest of your life, sometimes. You might play for a couple of years, you might leave, but you’ll always go back to it.”

His work on behalf of migrants is inspired by his own journey, but he can see the updated approach that needs to be taken now, almost twenty years on from his own arrival in Ireland.

“New people come into the country and I think sport is the way to get them integrated but I think we need more. Maybe we didn’t need an integration officer twenty years ago but now the way the country has changed, maybe we need to change the way we do things.”

Books at One

His passion for advocacy isn’t confined to the world of sport. While Zak is the director of Sports Against Racism Ireland (SARI), he’s also part of the advisory group for Books At One, a charity organisation committed to providing creative and social spaces to foster a love of reading for learning, pleasure and connection.

“I don’t need Gaelic or hurling to be involved,” he laughed. “We’re trying to create a little community and you can see all over the country bookshops are closing, more people are going online, but you want to keep that little community spirit, get people back reading.”

A surprising cause, perhaps, for a sports star, but a testament to Zak’s own commitment to continuing to create the sense of community that embraced him and his family all those years ago.

“I always say, when you’re reading you become educated, and when you become educated, you get jobs, and when you get jobs you can become rich, or you can live a normal life. But if people don’t see bookshops in their areas they are not going to read. If they don’t see one, where can they come in and have a cup of coffee and have a chat?”

He recalls how throughout his life, in all the places his feet have landed, from Leitrim to Dublin to Tallaght, people looked after him and his family well.

“But I wonder are they getting the same treatment as we did twenty years ago? Things are a lot different now as well, because of the housing crisis. There’s a lot going on, but like, what do you do when someone’s knocking on your door looking for help? You’d have to help wouldn’t you?’

Zak’s new book, Life Begins in Leitrim: From Kurdistan to Croke Park is out now with Gill Books.