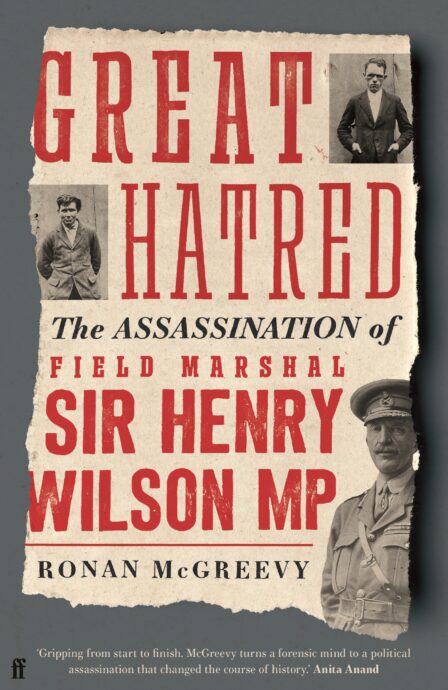

Great Hatred: The Assassination of Sir Henry Wilson MP|Ronan McGreevy|Faber|£20

“…a book as entertaining as it is informative…expressing a complex issue in a straightforward way.”

—Commander Daniel Ayiotis reads Great Hatred: The Assassination of Sir Henry Wilson, by Ronan McGreevy.

by Commander Daniel Ayiotis

I was recently honoured to have been invited to metaphorically cut the ribbon and launch Ronan McGreevy’s new book, Great Hatred: The Assassination of Sir Henry Wilson – a book as entertaining as it is informative.

When extending the invitation, Ronan said that he was particularly interested in having the Military Archives represented at the launch as his research drew significantly from our collections, particularly the Bureau of Military History 1913-1921, and the Military Service (1916-1923) Pensions Collection.

Archival collections

For those unfamiliar, these are the two most significant archival collections giving insight into Ireland’s revolutionary decade 1913-1923. The Bureau of Military History collection consists of 1,773 witness statements, collected by the eponymous Bureau in the 1940s and 1950s, from individuals who had been involved with the 1913-1921 period.

The Military Service Pensions Collection consists of the pension and associated files relating to applications made under the various Military Service Pensions Acts, introduced to recompense individuals and dependents for service and injury during the 1916-1923 period.

Accountability

The function of an archive in a democratic society is one of accountability, by ensuring the preservation and access to the documentary evidence of the decisions that affect and shape our state and our lives.

The Bureau and the Pension files have provided a wellspring of new primary sources during the Decade of Centenaries, providing new insights not only into military but social, health, economic and cultural history.

They have revealed erstwhile unknown stories of the rank-and-file of the revolution and the citizens caught in the crossfire. And they have elucidated new dimensions to a historiography that up until the 1970s at least, as described by Gerard O’Brien, confined the interpretation of the past to “the perception advanced by the republican revolutionary generation.”

Democratisation of Irish history

The books, articles, documentaries, artworks and conferences that these records, as well as those at other Irish archives, have informed, have facilitated a democratisation of Irish history.

They have also presented new, sometimes unexpected, sometimes uncomfortable, vistas onto the complexities, nuances, and multiple interpretations of previous grand historical narratives and national identities. This book is a fitting addition to this milieu.

We have learned in recent years about the traumatising effect of killing at close quarters on men like Charlie Dalton; we have faced the parallel legacy of Irish pride in the Connaught Rangers as both exemplars of the Irish soldiering tradition within the British Empire, and in their mutiny as a stand against that same empire.

Out of all of this, we have been forced to consider the meaning and implications of violence in the birth of our State.

Violence

That Irish independence was born out of armed struggle has often been treated with ambivalence. Sometimes it has been underplayed – the banner erected at the Central Bank during the Centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising, bearing the images of Grattan, O’Connell, Parnell and Redmond, was understandably received with confusion or ridicule my many.

Other times, the use of violence has been used to extend and justify its use from occasions of specific legitimacy to one of broad and unmitigated application.

In Afterimage of the Revolution, for example, Jason Knirck discussed the fallacy of describing those pro-Treaty Sinn Féiners who would eventually coalesce into Cumann na nGaedhael as “counter revolutionary” due to their refutation of the right of the anti-Treaty IRA to bear arms against Irish instruments of government, making the point that this is an argument which, by logical extension, implies that they were “incapable of distinguishing legitimate, viable and productive uses of violence.”

Complex issues

Great Hatred confronts the reader with two broad points – the complexities of Irish history and identity, and the obligation to critically analyse our attitudes to the use of violence for political ends.

Regarding the former point, this the story of the assassination of a British Officer and Politician by two members of the IRA. It is also the story of the killing of a World War One veteran by two World War One veterans. Slightly facetious, perhaps, but it is also the story of the killing of an Irishman by two Englishmen.

Regarding the latter point, the even-handed treatment of all personalities involved, with necessary criticism and without partisan indulgence, while communicating the colour of their lives through new archival sources, present the case that some acts, such as the killing of Sir Henry Wilson, were neither “legitimate, viable nor productive.”

This book expresses a complex issue in a straightforward way. History is complex, and I hope Irish archives continue to make it more so.

Commander Daniel Ayiotis is the Director of the Military Archives and a commandant in the Irish Army. His two forthcoming books in 2022 are The EU, Irish Defence Forces, and Contemporary Security (Palgrave) and The Military Archives: A History (Eastwood Books).