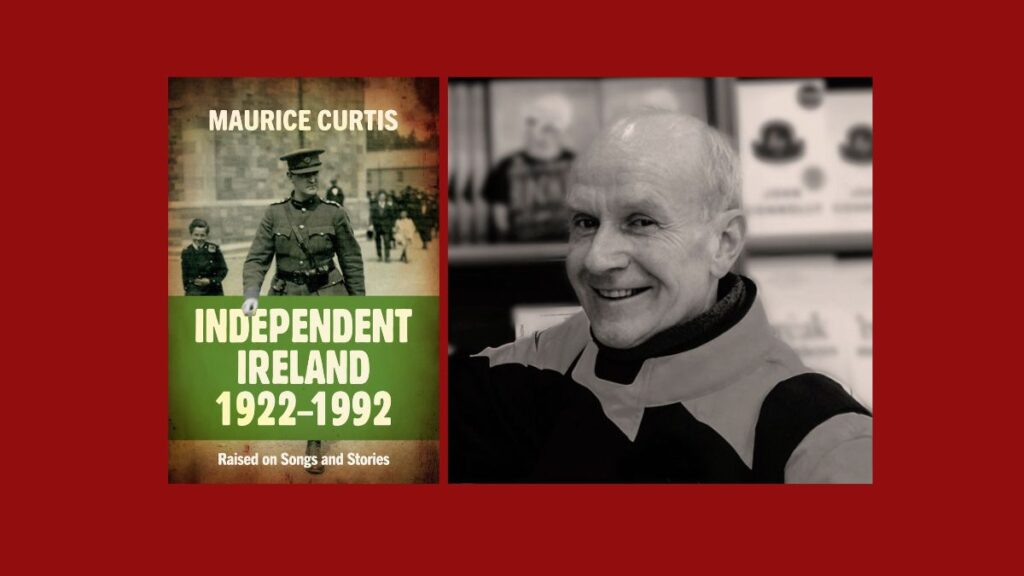

Maurice Curtis is the author of Independent Ireland 1922 – 1992: Raised on Songs and Stories, published by Orpen Press.

by Maurice Curtis

the story of 20th century Ireland is laced with many of the soundtracks of music that defined, reflected and shaped our destiny. Music as an intrinsic part of our identity was recognised by Thomas Moore, Patrick McCall, Percy French, but in particular, Thomas Davis. He is buried in Dublin’s Mount Jerome cemetery.

Not too far from Davis’s grave is that of Edward Bunting (d.1843), who achieved fame as a musician and folk music collector. He influenced Thomas Moore, ‘the Bard of Erin’ (Oft in the Stilly Night, The Minstrel Boy and The Last Rose of Summer), who in turn influenced Percy French (The Mountains of Mourne, Phil the Fluter’s Ball and Come Back Paddy Reilly).

In the 20th century many of these songs were kept alive by the Irish and internationally renowned tenor, John McCormack, and later still by Frank Patterson. The Walton’s sponsored programme on Radio Éireann ran with the line: ‘If you do sing a song, sing an Irish song.’

Early harpists

This particularly Irish musical strain had roots dating back centuries to the early harpists, flute and uilleann pipe players. The latter were renowned for the ‘Great Irish War Pipes’, played as the Irish went into battle and guaranteed to encourage the enemy to flee.

Despite the Elizabethan edict in 1571 that harpists were to be hung and their instruments burnt, the tradition survived and the blind harpist and one of the great Irish bards, Turlough O’ Carolan (1670 -1738), composed numerous poems, songs and lyrics, including 214 pieces of instrumental harp music.

Amongst the favourites are O’Carolan’s Concerto. He also composed The Lament for Owen Roe O’Neill, which the Young Irelander, Thomas Davis, used for a similar lament in the 19th century.

Thomas Davis

Thomas Davis understood the story-telling power of songs and music. Through the lens of suffering, love, emigration, and rebellion the history of Ireland over the centuries would be seen—and music would be called upon to invigorate the wider Nationalist cause of political independence.

This understanding ensured the popularity of his heroic songs of the dispossessed, particularly A Nation Once Again and The West’s Awake, with the emphasis on hope and courage.

During the 1798 commemorations, P.J. McCall took up the Davis baton and gave us At Boolavogue, Kelly of Killanne, and The Boys of Wexford. He also wrote the Pulse of the Bards, Songs of Erin and Irish Fireside Songs.

The national anthem

The fledgling Irish Free State also recognised the pivotal role its cultural heritage—and particularly music—would play in consolidating the nation.

In this respect, the national anthem Amhrán na bhFiann (The Soldier’s Song), 2RN (forerunner to Radio Éireann) and the Army Number 1 Band (using Moore’s Melodies for source and character of the national idiom), were regarded as crucial nation-building tools.

In fact, cinemas, theatres and dance halls played the national anthem at the end of the evening’s entertainment, a tradition that lasted until 1972.

Preserving musical heritage

Likewise, the pioneering work of Alan Lomax, Séamus Ennis and the Irish Folklore Commission, Garech Browne and Claddagh Records, achieved much in collecting and preserving our musical heritage.

Individuals such as harpist, Mary O’Hara (Songs of Erin), Seán Ó’Riada’s Ceoltóirí Chualann, as well as the Céili bands such as the Tulla and Kilfenora, fostered the unique Irish musical tradition and brought it to a wider audience.

Their efforts spawned younger musicians such as Altan, the Bothy Band, Clannad, Planxty, the Chieftains, Dé Danann and Stockton’s Wing.

Trailblazers

It was said of them that they ‘ensured we had apples in the Winter’. Some of the band members – Eleanor McEvoy, Mary Black, Dolores Keane, Sharon Shannon, Frances Black and Maura O’Connell – went on to produce one of the best-selling Irish albums of all time, A Woman’s Heart (1992).

The Dubliners folk group (despite having Seven Drunken Nights banned from Radio Éireann) led a musical stampede and were joined by The Fureys, Wolfe Tones and many more to give an Irish flavour to the international ballad boom.

These were the trailblazers that kept the tradition alive through the lean and good times.

Showband mania

Simultaneously, from the late 1950’s to the early 1970’s Ireland witnessed a showband mania that swept across the country with ballrooms springing up in every townland in the country.

At one time there were nearly 800 showbands travelling the country and it might be argued that with their live-wire music they dragged Ireland into the 20th century.

Some of the luminaries included Dickie Rock (‘spit on me Dickie’), Brendan Bowyer (The Huckle Buck) and Big Tom (Four Roads to Glanamaddy).

A member of one such showband was Rory Gallagher, who, reflecting the new mood, opted for a rock band (Taste). Others followed the new international music trends including Van Morrison (Them), Brush Shields (Skid Row), Horslips, Thin Lizzy, The Blades, Aslan and eventually U2.

Meanwhile, the showband era was edged out by disco fever, with ‘Europe’s No.1 Nightclub’, The Zhivago, leading the pack in the early 1970’s.

According to an advert it was ‘where love stories begin’. ‘But ended in the Rotunda’, according to a Dublin observer.