Eithne Shortall talks to Sophie Grenham about uplifting stories, community, and her new novel, The Lodgers

by Sophie Grenham

It’s a bright afternoon at Dublin’s Clarence Hotel, the lobby walls lined with powder pink banquettes while nondescript funk music pulsates. My guest, Eithne Shortall, breezes through the door looking effortlessly chic in a black halter top, tapered trousers and an embroidered jacket she bought on holiday in New York with her dad years ago. She cycled in, ever the committed peddler.

As Shortall folds herself into the seat opposite and orders a decaf coffee, she has plenty of questions for me, which is no surprise given she’s been a journalist since she was 21. In 2022, she accepted redundancy from The Sunday Times Ireland where she worked for most of her adult life as an arts features writer, later branching out into editing. She now works full-time as an author and has five novels so far. She also writes a parenting column at The Sunday Business Post while Nadine O’Regan is on maternity leave.

“I feel defensive of the north side of Dublin,” she says, jokingly

Shortall is from Drumcondra, north Dublin. While she has lived in the US, London and Paris, she put down roots with her videographer partner, Colm Russell, and their two children, Ruan and Nora, a few minutes from her parents’ house. At the time of buying, they were also in the market for a place in Skerries but that fell through. “I feel defensive of the north side of Dublin,” she says, jokingly. “I like the south side too but sometimes people on the south side are like, what is North Dublin? That makes me more patriotic, proud of coming from this area.” She’s also mad about Mayo, where her parents own a bungalow in Louisburgh, twenty minutes from Westport.

The Lodgers

Shortall is easy to fall into verbal step with, and she’s naturally funny. Her books contain the same warmth and cheer she displays today. If one were to package her, you could say she’s Marian Keyes for Millennials, although plenty of Millennials already worship Keyes, who called Shortall’s work “fresh, funny and very charming.” This includes Love in Row 27, Grace After Henry, Three Little Truths and It Could Never Happen Here.

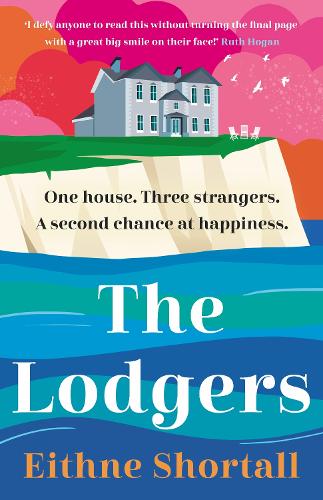

Her latest offering, The Lodgers, is about a formidable 69-year-old widow, Tessa, who opens her home to two lodgers after she suffers a nasty fall. Chloe is fleeing a disturbing home situation while Conn grapples with a family bereavement. Hope House rests on a cliff with breathtaking views.

Shortall is easy to fall into verbal step with, and she’s naturally funny

Shortall has said that The Lodgers is her favourite of her novels. After having gone through the lengthy publishing process five times, does it feel easier this time around? “It really doesn’t,” she confesses. “If anything, the opposite. I’m annoying to my publishers in that the four books before this, they’re all vaguely in the same wheelhouse of popular fiction, but the first two are more love stories and the latter two are more suburban mysteries.”

The Lodgers is a mix of both genres. While you can see how this might frustrate publishers, the fact that Shortall’s work can’t be pigeon-holed means it’s less likely to stagnate. “They would love if you wrote one thing every time, but that’s not how I work,” she continues. “When you’re writing, when you’ve already written other books, you’re thinking, I’m supposed to be writing something similar to those. Is this similar enough, but also different enough that you’re not just repeating yourself? You start considering these impossible-to-answer questions. I don’t find it any easier now and I’m surprised by that.”

Hopeful

Shortall is relaxed and no topic is off-limits. She talks very quickly at times, her sentences almost bleeding into each other as she jumps from thought to thought, but it’s easy to follow her tangents. What does she love about The Lodgers? “I found it comforting to write and to exist in,” she says. “When I start a book, I think it’s going to take you nine months to a year. Do you want to be in that world, dealing with whatever the issues are for that length of time?”

The news can get wearing for Shortall and she needs regular respite, like many of us do. “In general, I would say I find the news harder to take,” she says. “The older I get, the more affected I am by things in the world. I still engage with news because I want to be a responsible citizen, but I try to limit it. It can get to me and then I find myself gravitating towards films and books that are hopeful, because the world is hard enough as it is.”

The news can get wearing for Shortall and she needs regular respite, like many of us do

When Shortall started writing The Lodgers, the invasion of Ukraine had begun and she found herself depressed by the developments. Then she saw people in Ireland offering to house refugees. “I found that really gorgeous. A lot of people were never taken up in their offer, but it was such a lovely gesture to see,” she says, heartily. “If this invasion of Ukraine decimated your faith in humanity, this offer was restoring it.”

Their generosity sparked the idea for Tessa taking in Chloe and Conn. “Obviously they’re not refugees, but this woman has a big house and she will benefit to an extent too. It’s a relatively selfless act, even though she’s curmudgeonly about it at the beginning. That’s a hopeful environment that I can spend time in, and all three of them are coming from families that have taken a punch. My books are all about finding a community.” In this case, Tessa, Chloe and Conn gradually become their own family unit. Then you have a wider community which is fighting to stop the closure of their beloved community hall. “They have their own hardships, the world isn’t perfect, bad things happen – but there has to be hope.”

Darkness and light

Tessa is based on her own grandmother Teresa (Tess), who has played a role in each of Shortall’s books. “I love her but she’s not nice,” she says, wryly. “She’s mean, she’s got a sharp tongue, she’s bright and she’s cross. You think of old women as being all lovely and nice – that’s not her. If you have a spot, she will let you know. If you’ve put on a couple of pounds, she will let you know. She’s not perfect. She’s not holding back and she doesn’t give a shit and I love her for it.” The house in the book is based on Granny Shortall’s, a big midlands house from the 1700s, complete with damp and no central heating, but with a huge history.

As is her forté, Shortall has assembled a fine gang of characters who get together for various causes, and Tessa teaches a class at the community hall, brilliantly called Radical Activism. Also on offer are Rhumba for Retirees, Tai Chi and Decaf Tea and Darts and Crafts. You see the classic tropes of a neighbourhood group, and you’ll no doubt be charmed by the socially inept Malachy whose shaved head goes bright red at the slightest provocation.

I write the little guy winning because they never win in real life.

Shortall was stirred by the happenings of the Corpus Christi north Dublin community centre where she went to Scouts, owned by the church. “They basically cleared out all the activities that were in it, after-school classes,” she explains. “They were shutting it down and didn’t say what they were planning to do with it. People presumed that they were going to build apartments there. I hoped they would win and keep their hall but I thought it was hopeless. I didn’t think they were going to get anywhere.” To her surprise and delight, the church acquiesced and gave it to the primary school beside it. It will be used for community purposes, but apparently this seldom happens. “The little guy never wins. I write the little guy winning because they never win in real life.”

One of The Lodgers’ darker themes is suicide, which Shortall gently and respectfully handles. Some of the scenes are quite powerful and gut-wrenchingly sad. How did this come into play? Her voice drops. “I think almost everybody has an experience of it. I know I do. With suicide, the effect on a community is devastating. In this case, it’s a brother. It can be your friend, it can be a cousin, and you will still feel a sense of responsibility. It’s valid because you think, what if I’d just done one thing differently? It is actually possible that could have changed something – it probably wouldn’t have. It’s harder to get closure on. The effect on a community is huge, and it goes out and out and out. I think it’s more complicated than any other kind of loss.”

Journalism

As with her other work, where there is darkness, there is also light – a love story. In recent times, the traditional rom-com movie seems to have gone out the window, which is an awful pity. In The Lodgers we see Chloe and Tessa work their way through classics film such as Four Weddings and a Funeral. Shortall enjoys a good romance and has read plenty of novels in this vein recently. Chloe and Conn even have their own meet-cute as they initially vie for occupancy at Hope House before Tessa decides to take in both of them.

Like any great romantic story, there is a love rival in the form of hungry journalist Paul, a former boyfriend of Chloe’s who she enlists to gain publicity for their community centre crusade. Borrowing from experience, Shortall based him on two well-known Irish male journalists. “A big part of it is the obsession,” she says. “I never had that kind of ambition. I think it’s great in one way. If you’re a real [mock serious voice] news journalist or a hack, you’re going to get the stories. You need to be dogged and you need to be obsessive. I never was but I worked with them and I met them at things. There is that obsession now with social media following numbers, always checking how they’re doing and if it’s going up. That would drive you insane, but they base their work on it and it’s so unattractive [laughs].”

When Shortall left The Sunday Times Ireland, having small children was a large part of it.

It’s not difficult to picture the archetypal driven, self-serving hack – there’s plenty of them about. “Everything is for online approval, it feels performative, even things they get impassioned about. Do you actually care about this issue or is it that you know being this way may do well online? I was never a news journalist. I have no interest in writing 800-900 words on what’s going on in RTÉ or how government parties are doing.”

When Shortall left The Sunday Times Ireland, having small children was a large part of it. “Your job defines you to an extent. For me that got less so as I got older. I was so young when I started, and it definitely defined me,” she says. “I thought it would be harder to leave, but kids take up so much time and head space and you’re just busy. Even if I had no job, I’d feel busy with them. It just keeps going and you almost don’t have time to think about the change that has just happened.”

Shortall found herself behind on her book deadline, then redundancy came up at the paper. “They didn’t think I was going to take it but I was like, this is a sign. Leave, take the money, pay down some mortgage, and just concentrate on writing. After two children, it was just impossible to do all of the things. Everyone has their limits and I was definitely at mine.”

Writing

How does she manage writing at home? “When they’re in childcare it’s fine, but I think my biggest difficulty now is space. I have a yard. I don’t have a garden. I crave a garden in which I can put one of those sheds [to write in]. We don’t have full-time childcare,” she tells me. “It is a choice and we may well change that. At the moment we have three days a week, then we share the other two days. Even if they’re in the house and I’m not in charge of them, they’re still there. I can hear them there. I do that find that tricky.”

“At the moment, I think it’s horrendous but I remind myself that the first draft is always horrendous,” she says.

While the local library has proved a haven for many people, not all have flexible hours and you’re not guaranteed silence. “Maybe there is no correct place to work,” she reflects. “I try to have a mentality of it just has to get done. Even if you don’t have your optimal conditions, you just keep doing it. I used to do a lot of writing in my parents’ house in Mayo and obviously that’s harder now. I went on my own for the first time for a week and it was brilliant. It was very enjoyable to be on my own. I got so much done and my partner is very encouraging of that kind of thing. Maybe twice a year for a week I will go on my own and write. I will probably get more done than I would have before because it will mean so much to me.”

What is she allowed to tell me about the next book? She has just finished the first draft of book six. “At the moment, I think it’s horrendous but I remind myself that the first draft is always horrendous,” she says. “I am trying something completely different that wouldn’t fit with anything. I don’t know if it will work or not. I’ve always wanted to write this book so I’m just doing it now. I won’t say anything except that it’s completely different.”

We wrap up our hour with Shortall’s final thoughts on The Lodgers, before she speeds off to collect her daughter from crèche. “I’m not trying to change the world ever with anything I write. I actually think the world has enough books,” she says, sincerely. “There’s absolutely no need for me to write a book, or anyone – there are enough out there. I’m never trying to say anything huge. Same when I was a journalist. I wasn’t interested in those big angry stories. I’m interested in the personal and people can connect to that.”

Sophie Grenham is a freelance arts journalist from Dublin who has contributed to The Sunday Times Ireland, The Sunday Independent, The Irish Times, and The Irish Independent Review. Her debut short story, “14”, was published in Tír na nÓg magazine’s inaugural issue in 2020. Twitter and Instagram: @sophiegrenham