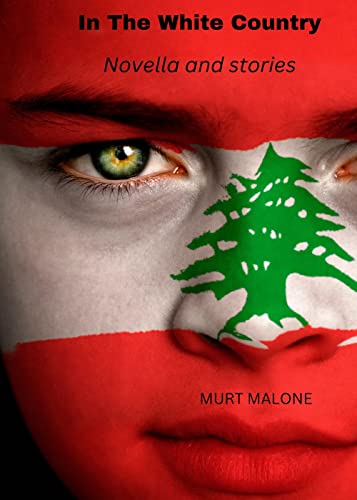

From the collection In the White Country: Novella and Stories| Owl Fella’s Press

In the White Country, by Martin Malone

(White; Lebanon, from the Arabic lubnān, referring to snow-covered Mount Lebanon)

1996

Tariq shifts to make himself comfortable in the green polypropylene chair. Nurses an espresso like it is a last wish. Shifts again. His eyes drift from under the café’s candy-striped awning, across the road, to the Roman hippodrome. Wonders if he closes his eyes tightly and reopens them if he would glimpse Ben Hur on his chariot? He is a slight juvenile with shaven hair and narrow shoulders. His cheeks are like sinkholes. An eye-tooth has gone wayward so when he smiles it is because he has forgotten about this. He wears light-grey cargos, white trainers, and a mint-green Puma T-shirt. Tired looking clothes, the stamp of rough sleepers. Tariq is missing from home, for reasons he has begun to question.

A week ago he had hitched a ride to the fruit farm, as far as Al Bayyadah village, and alighted, because the pickers were turning right. And he wanted to keep on the coastal road. Opposite the Fijian UN checkpoint, at an ice cream vendor’s stall, he met Albir and they struck up a conversation. Over melting vanilla dripping from nibbled cones, the boys soon found common ground in hatred. Albir showed him photographs…If anger had pushed Tariq into leaving home, these Polaroid stills heightened the blaze. Did not help him in his struggle to keep it to a paltry flame. It burns even when he sleeps, he is sure.

He glances at the imitation Seiko on his wrist. He had to pierce a hole in the black strap to ensure the watch did not slip from his small wrist. Often he still has to right its face and needs to pierce another eyelet. The watch runs slow but his red travel clock doesn’t. Because it’s a travel clock it is stronger than ordinary clocks and can travel everywhere, without breaking. And its alarm is perfect for waking them up – if he remembers at night to wind it. In his green cloth backpack there is a cedar figurine of a horse, his luck sake, a couple of T-shirts smelling of ocean after being washed and laid to dry on the rocks, a pair of blue Adidas sandals and some cellophane wrapped hard-boiled sweets. Albir took control of his few dollars, as he is older, and an expert at making money last. His friend has been quiet since they arrived in Tyre. He has a cellar of old hurts, more than Tariq, Albir declares, but Tariq privately disagrees. His justifications for running away from home are as important as Albir’s. There are differences; Albir Assad left home in Sidon because his father beat him and his mother did too, whenever she thought his father had not beaten him enough. Beatings distributed at his uncle’s behest. The unwanted find others of their kind, Albir had said. He is short, stocky, with a scar above the corner of his lips and another across his forehead like a pink sickle. His eyes recede, as though they peep from a yard behind a window.

The boys make for a solemn picture, down to their last US dollars and Lebanese pounds, and it is Albir who breaks the silence by announcing they need to come up with another plan. Thus far, and though Tariq considers mentioning it, he keeps silent – their plans have come to nought. Amal wouldn’t recruit them nor Hezbollah. Albir had friends in each organisation and they gave him contact details for recruitment officers, but he suspects – he admits to Tariq – they had not pushed their names forward as they’d promised – or if they had – they hadn’t fully vouched for him. Or you, Tariq.

Vouched, Tariq considers – is it something like a voucher? That is a good thing. You get free things with a voucher. Discounts. Why wouldn’t Albir’s friends say nice things of him? They are his friends. Though Mama Sawsoon says people can pretend to be your friends. And do bad things behind your back, where you don’t have eyes to see. Followed this, after staring at the withered cactus she had been trying to revive on the kitchen sink, by saying, Tariq – even if you had eyes in the back of your head, you would not believe what people do…or say.

“Any ideas, Tariq?” Albir says, looking at the eye of his cigarette, as though there is a hope of a better response from it. “Thank you very much for asking, Albir – but I have nothing to say for now.”

“Nothing, really?”

“We could try the Amal again – they were smiling when they spoke to us, weren’t they smiling?”

Albir says, shaking his head, “What part of what they told us don’t you understand? They said we were to fuck off, to never fucking come back, and if we did they’d shoot us in the ass and feed our balls to their goats.”

Tariq nods. Yes, he thinks, they weren’t nice, when I think on it. How can people smile when saying such bad things? Allah wouldn’t like to hear Albir using gutter Yankee language. Mama Sawsoon would show him her sharp eyes and not give him ice cream for dessert.

“We won’t go back there,” he says, “thanks Albir for reminding me.”

“We’ll think of something. Meanwhile, let’s go to watch the girls coming out of school.”

“For what?”

“What do you mean, for what?”

“They have nice blue uniforms for sure. But the sea is nice too – let’s go to the harbour instead and ask a fisherman to bring us with him – we might catch…”

But Albir is up, flicking his cigarette butt to the ground, driving his heel into it, and Tariq understands he can either follow him or stay behind, and there is no telling if Albir will come back for him. When he catches up with Albir, the older boy says, “Now when we look at the girls, we have to do it without looking, right?”

“Look but don’t look,” Tariq says, puzzled.

“That’s it.”

“Albir, show me how.”

Albir draws up short, “Spare me. This is how.”

He looks straight ahead, almost, and says, “See the tractor coming up the road – I’m watching that, but I’m really looking at the blue van a bit behind it.”

“Okay,” Tariq nods in understanding, but asks, “why don’t we want the girls to know we are looking at them?”

“That’s just the way it is.”

Tariq decides he will study Albir to see how he does it. He finds it easier to learn by staring at the doer, and what he needs to do then seems to slide into his brain. That’s just the way it is. Albir is smart. Mice are smart too, but even so they end up in traps. Who was it had said that to him? Rafa? Mama Sawsoon?

They move into place across the street from the school. Albir regards the schoolgirls walking in single file and in pairs and threes along the opposite footpath. Tariq studies, and while they have slowly left the school behind, Albir says, “How many did you like the look of?”

Tariq deliberates. He had not run his eye over any of the girls.

“Them all,” he replies.

Albir slaps him on the back, laughs, and says, “Good, you’re learning.”

Learning? Tariq thinks – not to look straight at people?

Later at their flimsy shelter on the beach, in a dip among grassy topped dunes, they light a small fire before night falls, and talk of the things mutual to them.

“…here, you didn’t ask me,” Albir says, poking the fire with a small twig, creating a dispersion of sparks.

Tariq’s silence prompts him to continue…

“Which of the girls I liked best of all.”

“Which, Albir?”

“Just one. She’s my cousin, Fatima. She is very pretty. I like her a lot.”

“Does she like you back?”

“She smiles at me whenever there is no one else about. I sent her a poem I stole from a book – it said, “…Your smile would light up a way from a dark place.”

“Did she send you one?”

“No. I’m not even sure if her brother passed it on to her. I think he gave it to his Papa to get him to kill me”

Silence.

“Her Papa caught up with me – he tore the note into strips and forced me to eat it.”

“Was it nice?”

“What do you think, camel head?”

“How old is Fatima?”

“She is fourteen on her next birthday – which is in three weeks. She—”

“And you are 18 on yours. See? I remember.”

“I didn’t tell you when I was born.”

“I heard you telling the Hezbollah man.”

Night settles in. Stars are prevalent in a clear sky, as are low hanging strings of amber lights on a cargo vessel cresting the horizon. A mild sea breeze whistles with the reeds, waves splash gently to shore, and into this rhythm the boys search for sleep. Tonight, they have not spoken of the anger. Mentioning it and thinking of Qana brings it toward boiling point; when imagined, when discussed. April 18th. The day the Israelis shelled the village and killed 108 people. Albir keeps close to his person Polaroid images of some of the victims; in a bag with his camera, and an M16 rifle bayonet he had stolen from a shop off Rue Abu Dib, while Tariq drew the owner’s attention by behaving oddly, or as Albir stated, being himself. Retarded just enough to make people question themselves if he truly were. He said retarded as though it was not an insult but advantageous. There was no spite or belittlement in it – though Mama Sawsoon said it was a bad thing for someone to call him. Bad people know bad words and use them, good people know of them but never let them drip across the corrals of their lips. Wise woman, his Mama Sawsoon.

Tariq surveys the stars and remembers that Papa had shown him the Panhandle, and there it is. Like a saucepan. Though told the names of others, he forgets those. But he remembers Papa’s Daoud’s hand on his shoulder, finger pointing upwards, and Mama calling them indoors. Mama Sawsoon who wants a better life – she is always telling Papa this – she does not want to become an old woman with nothing to her name. Always having to count midget money. She wanted a ‘life’. Away from the village, the street, from the road on which their daughter died, where she puts flowers every anniversary and on her birthday – it is the spot where her soul left for Paradise, the spot where her blood drained into the earth. Tariq had overheard her telling Papa Daoud those things…And she envied the dead, for their suffering was over and they had yet to face into theirs. Papa said she should consult with a doctor. She goes on like their daughter-in-law Fatima. Always a want in her to want more.

If someone constantly repeats something it washes out your brain, Papa Daoud had said, and replaces your thoughts with theirs. And Rafa wasn’t the strongest of men, he added. Lacked a spine. Tariq simply had to ask what a spine was and Mama Sawsoon barked at him not to be eavesdropping – people who do that learn bad things about themselves, which confused Tariq further. Adults speak in too many tongues.

“Do you want coffee,” Tariq says – “I can’t sleep. Can you?”

Albir says. “We have coffee. Just two sugars. Nam. Mucho gratias, Amigo.”

Tariq understands he has been tasked to put water in the coffeepot, poke the fire to life, and brew Albir a glass. As usual, when this is done, Albir will be asleep and Tariq will drink the two glasses and see the morning scarves of light steal through.