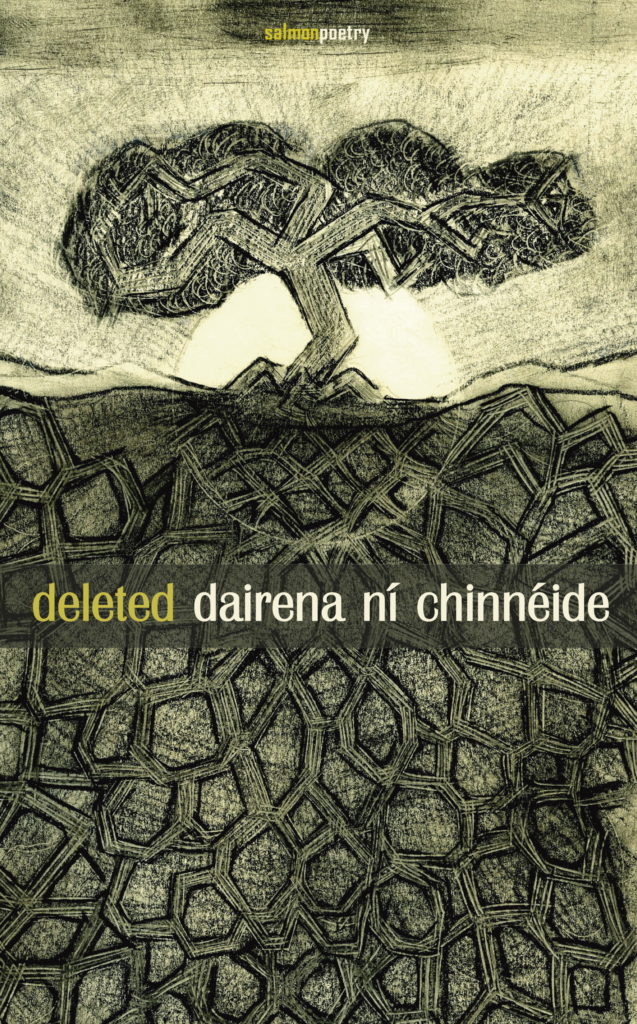

deleted

by Dairena Ní Chinnéide | Salmon Poetry | 84pp | €12 pb | 9781912561780.

This is Kerry-born Chinnéide’s first poetical outing in English, with nine collections in Irish already. Once a recognised voice on the now-defunct Century Radio, her collection was launched by actor and friend Aidan Gillen last November. Irish Mirror journalist Paddy Clancy remarked that the book’s cover was originally produced upside down, making the publication a sort of collector’s item. The error has since been corrected. The collection is shortlisted for the Shine/Strong Award, which will be announced on 29 March.

When an ostensibly Irish-language poet decides to write in English, does something happen to the work? Why make such a change at all? One might think of the late Michael Hartnett’s Inchicore Haiku (1985)—incidentally, the first time a collection of haiku was published in Ireland—or his Poems in English, or his marvellous A Necklace of Wrens (poems in English and Irish) among work that, for me, marked him as a genuine link between two languages and two worlds, one much more ancient than the other, and even, perhaps, a conscious confusion of identity.

Having two languages to compose in can be a bit like having two left feet, or it may be a creative blessing. One foot may still rub the other, if the awkward metaphor may be extended: the Irish language might inform the English. Sometimes, however, poets who have published originally in Irish with facing translations into English by other poets have sent up, for me at least, red flags. Is this illustrative of an unconscious dissatisfaction with Irish? An acknowledgement of the smaller readership for literature as Gaeilge? Consequently, is it merely reaching out for a wider audience? In that sense, a publisher’s gimmick?

Ní Chinnéide’s poems in English are, however, not translations: here is a deft sensibility coupled with a straight-talking originality in the language of ordinary emotions. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, there are regular castings-back to an older legacy of mythologies and chieftainship, which, taken together, constitute a harkening to a different and concrete social order, a Gaelic culture that was outside English and that cannot be ignored as mere history. This may rub uncomfortably against the tastes of a younger readership, embroiled in a world of ‘performance’ poetry, reading from mobile phones rather than paper, too often without any sort of order at all or point of reference beyond themselves.

But, nevertheless, it stands as a tribute to Ní Chinnéide that she has almost defiantly resurrected what is, after all, the base upon which Irish poetry is constructed. Neither is she overly romantic about the use to which the Irish language has been employed. ‘The Gaelic Lover’ is tongue-in-cheek, somewhat like the seventeenth-century’s Daibhí Ó Bruadair:

The perfect lover

leaves like Irish

in the morning

when the rest of life

invades your condition …

Elsewhere, no less scathingly, she attacks the ‘game of football’ that the Irish language has too often become, as in ‘Irish & The State’:

… on home turf there was now a trendy pride

a Gaelic rap-fest at half time

urban followers now chanting

In the first language …

I am reminded of a remark by a friend and poet in Conamara, to the effect that no one in his home listened to RTÉ’s Irish-language news, because they couldn’t understand it. There is, it seems, an ersatz form of the language.

Outside of her satire, Ní Chinnéide brings her pen to bear on everything from NAMA to motherhood to Mozart. There is nothing retrograde about her work; she is a very modern poet, though one wonders whether there isn’t just a little too much emphasis on woman as warrior in some poems. That designation is not new but it may be increasingly thought to be irksome. Ordinary daily life does not make a warrior of anyone; and ‘warrior’ and ‘victim’ can arguably become interchangeable. I don’t know that male poets ever argue that a man is a warrior merely because he has ordinary life to face, in all its trials. Does it not smack somewhat of camouflage, certainly of distancing?

It is disappointing to spot typographical errors (one must suppose this is what they are) spicing the work. Should ‘copula’ really not be ‘cúpla’ (p. 22); ‘specters’ not be ‘spectres’ (p. 26); ‘Gods’ not be ‘gods’ (pp 36 and 37); ‘Artic’ not be ‘Arctic’ (p.53); ‘cause’ not be ‘because’ (p. 71); and all easily corrected in the proofs?

What is undeniably attractive about these poems—and, yes, they often lack a lyric quality that makes many a poem very different from prose—is the plain speaking, the directness that is not quite the same as that dreadful excuse-word ‘accessible’. These poems have a genuine appeal and necessity, particularly when we find ourselves in an Ireland that often seems culturally neglectful or, at best, confused, and where women are (let’s face it) still under threat from forms of ominous indifference, some of it official. The title deleted [sic] may be more significant than we first imagine.

by Fred Johnston

Six-week online poetry course:

Poet and novelist Fred Johnston is offering again a six-session online course for those interested in writing prose or poetry. The series comprises six lessons with exercises and reading recommendations and feed-back on submitted work.

Those interested should contact fred.poet@yahoo.com. Suitable for beginners and novices who have published work. Course fee is €100.