‘Slavery has divided society into two classes:

to the one it has given power, but to the other it has not

extended protection. One of those classes is above public

opinion and the other below it; neither one therefore is

under its influence.

Lord Sligo, Governor General of Jamaica.

Anne Chambers discusses how the above observation, in view of the present struggle for racial equality worldwide, seems as relevant today as when first written in 1836.

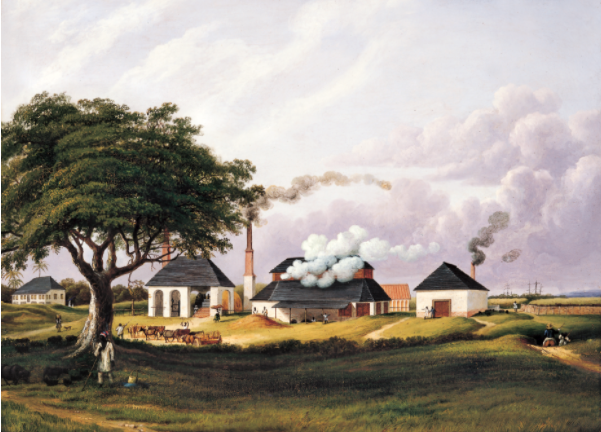

Lord Sligo, from Westport House, Co. Mayo, Ireland was appointed Governor General of Jamaica and the Cayman Islands in April 1834. While the importation of slaves from Africa had been abolished in 1807 slavery, the cornerstone of sugar production and profit, continued. Evangelical missionaries conveyed the horrors of slavery to the British public and in 1833 the government passed an Emancipation Act which Sligo was entrusted to implement in Jamaica.

The Emancipation Act, however, did not give immediate freedom to the slaves, who merely became ‘apprenticed’ to their masters for a further six years. Described as ‘slavery under another name’ the controversial ‘Apprenticeship System’ was nonetheless resisted by the Jamaican Plantocracy and by powerful commercial and political vested interests in Britain.

As the owner of two plantations on the island which he has inherited from his grandmother, Elizabeth Kelly, heiress of Denis Kelly from Co. Galway, former Chief Justice of Jamaica, the Jamaican planters expected Sligo to be on their side. His objective, however, as he told them on his arrival as Governor General in April 1834, to establish a social system ‘absolved forever from the reproach of Slavery’ set them on a bitter collision course.

Sligo found the savagery of the slavery system he encountered personally abhorrent. From the flogging of field workers with cart whips, branding with hot iron, to the whipping of female slaves ‘the cruelties are past all idea,’ he told the Jamaican Assembly. ‘I call on you to put an end to conduct so repugnant to humanity.’

To counteract the worst excesses he maintained personal contact and control over the sixty Special Magistrates appointed to oversee the implementation of the new Apprenticeship System in the nine hundred plantations throughout the island. As he wrote to a friend

‘It is treason in Jamaica to talk of a Negro as a free man

or to speak to him or to give him any knowledge of the

extent to which the law protects him…‘

Much to the derision and indignation of their masters, and unprecedented in the colonies, to alleviate such inequality he personally ‘gave a patient hearing to the poorest Negro which might carry his grievance to Government House…’

Against opposition from the Jamaican parliament he advocated the education of the black population so they might extract maximum benefit from their future freedom. He supported the building of the first schools on the island, two of which he established on his own property. He was the first plantation owner to initiate a wage system for black workers on his own plantations and later, after emancipation, to divide his lands into small farms which were leased to the former slaves. His efforts to improve Jamaica’s infrastructure, land reclamation and better husbandry practices, as well as to steer the economy away from its dependence on sugar, lead to the establishment of Agricultural Societies of which he became patron.

His efforts on behalf of the majority black population were bitterly opposed by the planter-dominated Jamaican Assembly who accused him ‘of interpreting the laws ‘in favour of the negro’ and who, as Sligo noted, set out ‘to make Jamaica too hot to hold me’. Derisorily referring to him as ‘The Great Leviathan of Black Humanity’ they withdrew his salary and commenced a campaign of vilification against him in the Jamaican and British press. With the connivance of powerful commercial and political vested interests it resulted in his removal from office in 1836.

To the Jamaican black population, however, Sligo was their champion and protector as the pro-emancipation press on the island recorded:

‘The shout of fiendish triumph that sends Lord Sligo from the shores of the colony is the prelude to the acclamations that will hail him a DELIVERER of the human race, as a friend of suffering humanity, as one of the truest champions of liberty…’

In an unprecedented gesture the black population presented him with a magnificent silver candelabra inscribed:

‘in grateful remembrance they entertain of his unremitting efforts to alleviate their suffering and to redress their wrongs during his just and enlightened administration of the Government of the Island…’

Lord Sligo’s experience in Jamaica turned him into ‘the warmest advocate for full and immediate emancipation’ and on his return he became active in the anti-slavery movement in Britain.

One of his published pamphlets ‘Jamaica Under the Apprenticeship System’ influenced the ‘Great Debate’ on Emancipation held in the British parliament in February 1838.

On 22 March 1838, being as he wrote, ‘well aware that it would put and end to the [slavery] system’ Sligo announced in the House of Lords, that regardless of the outcome of the government’s deliberations, he would free all Apprentices on his own plantations in Jamaica on 1 August 1838.

‘I am confident that no person who is acquainted with the state of the West Indian colonies and at the same time uninfected with colonial prejudices will deny that the time is now come when it is important to effect a final arrangement of this question.‘

His public pronouncement left the British Government with no alternative but to implement full and immediate emancipation on the same date.

Sligo’s efforts in Jamaica also influenced the struggle for emancipation in America. In September 1836 in New York and Philadelphia he met with members of the newly-formed American Anti-Slavery Society, as well as with individual clergymen at the forefront of the emancipation struggle and, as was recorded, ‘all who met him formed an exalted opinion of his integrity and friendship for the poor.’

Lord Sligo earned an honoured and respected place in the history of Jamaica, where he is acknowledged as ‘Champion of the Slaves’ and where Sligoville, the first free slave village in the world, is named in his honour. In 1838 his name, together with Wilberforce and Buxton, leading figures in the anti-slavery movement in Britain, was also commemorated in an emancipation memorial medal.

That many of the racially-motivated inequalities and injustices that Sligo sought to eradicate during his lifetime still exist one hundred and seventy-five years after his death he could undoubtedly not have envisaged.

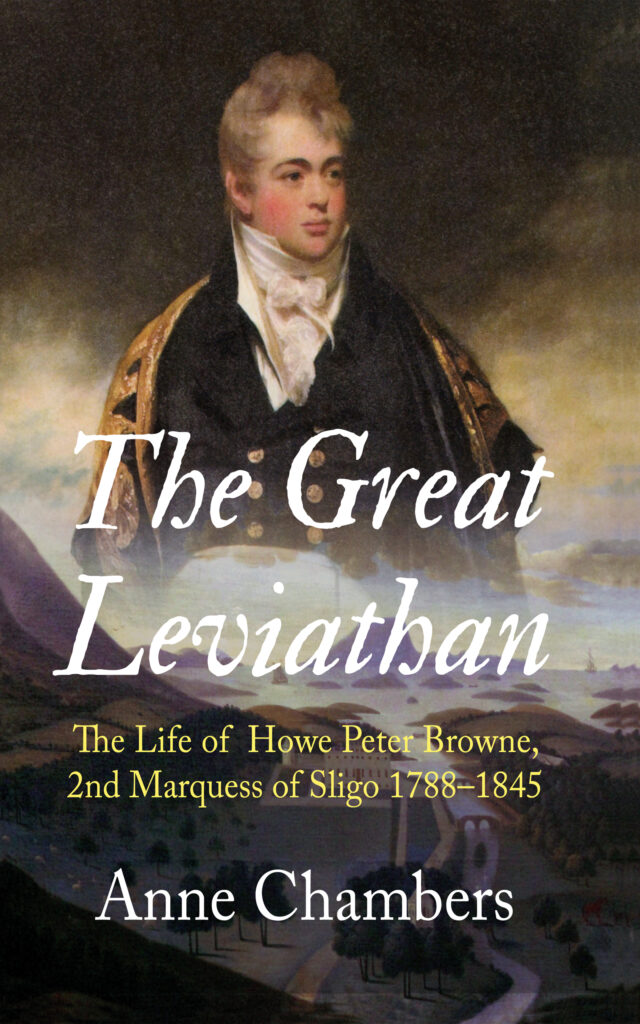

Anne Chambers is a biographer, novelist and screenwriter. Her books include Granuaile: Grace O’Malley – Ireland’s Pirate Queen, The Great Leviathan: The Life of Howe Peter Browne 2nd Marquess of Sligo, 1788-1845. and TK Whitaker: Portrait of a Patriot. Her books have been the subject of TV and radio documentaries for Discovery, the Learning Channel, the Travel Channel, RTÉ, Lyric FM and the BBC.

The Great Leviathan – The Life of Howe Peter Browne 2nd Marquess of Sligo, 1788-1845. (New Island Books) €15 HB