Article by Laurence Cox

In 1911 an Irish radical was put on trial for sedition. This was perhaps not so unusual—except that the trial happened in colonial Rangoon and the Irishman was a Buddhist monk, famous across Asia.

Born Laurence Carroll in Dublin in 1856, he had worked his way across the Atlantic, crossed the States as a hobo and sailed the trans-Pacific routes from San Francisco to Yokohama. Ordained as U Dhammaloka in 1900, he became a celebrity figure in the pan-Asian and anti-colonial Buddhist revival and was active in today’s Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, India, Bangladesh, Japan and Australia, and perhaps in Nepal and Cambodia as well, challenging what he called ‘the Bible, the whiskey bottle and the Gatling gun’—the combined forces of missionary Christianity, cultural destruction and military conquest.

Dhammaloka’s rise to fame began on the Shwedagon pagoda, where he confronted a policeman wearing shoes on Burma’s most sacred site and in the process launched the ‘shoe question’, which would become central to Burmese anti-colonialism. Shoes are considered dirty in Asia (recall the Iraqi journalist throwing his at George W. Bush), and white tourists and colonial forces wearing shoes on Buddhist holy sites was seen as ‘trampling on our religion’. Drawing on Irish models, Dhammaloka was able to use local religion to challenge colonial power.

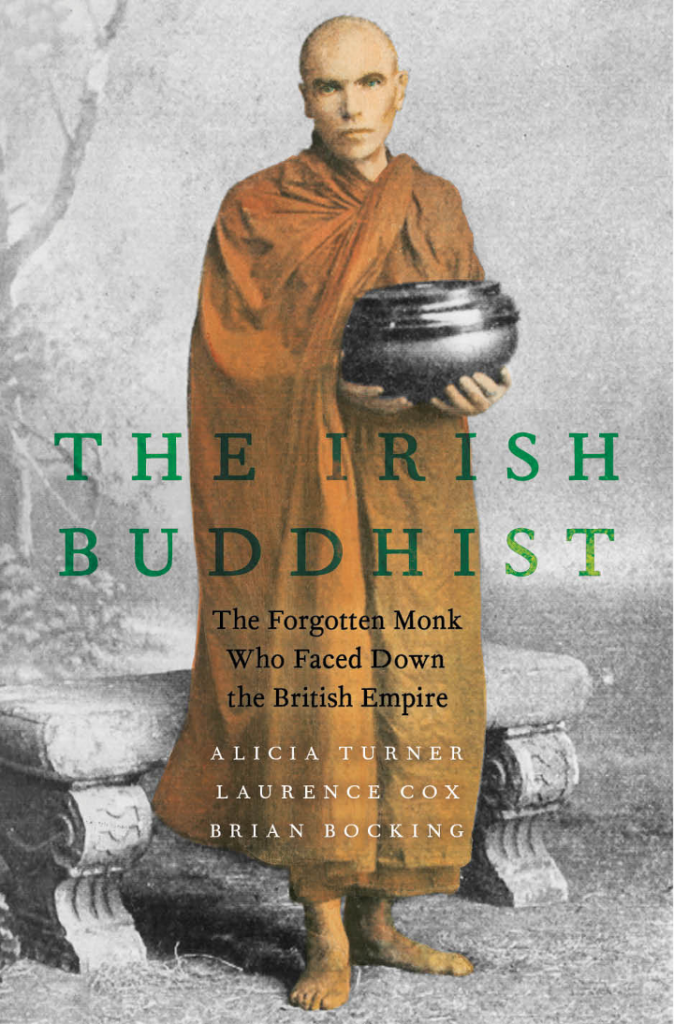

In a British Empire that depended on strict racial boundaries between ruler and ruled, the sight of a European wearing native clothes, going barefoot and begging for his food was a stark challenge to hierarchies based on skin colour. Where empire increasingly justified itself as bringing the gospel to the heathen, a white convert to Buddhism upset everyone’s assumptions. With Irishmen so involved in the British army in Asia, the figure of an Irish Buddhist was a worrying suggestion of possible alliances across the colonies—and central both to Kipling’s Kim and Irish author Bithia Croker’s Road to Mandalay.

As an Irish sailor and hobo, Dhammaloka was a great storyteller and good at finding his feet in new places and situations. He needed these skills in a life filled with confrontations with authority: he drew a discreet veil over 25 years of his life, had at least five aliases, was put under police and intelligence surveillance, tried for sedition, faked his own death and eventually disappeared.

In the century that followed, Dhammaloka was lost to history. Later Burmese nationalists were uncomfortable with an Irish representative of their national religion, while Irish readers—who had found his exploits fascinating before the First World War—did not want to celebrate an Irish radical who had left the Faith. European Buddhists found him altogether too political for their tastes and decided that the ‘first western Buddhist monk’ was a polite English gentleman, Allan Bennett.

For the past ten years, Burma specialist Alicia Turner, Japanologist Brian Bocking and I have been working to piece together the story of his life, using newly digitised sources from many different countries—reading the voices of his colonial and missionary opponents as well as his own pseudonymous contributions, media polemics and the diaries of a close ally. In a world where the legacy of empire and race is still a hugely public issue, remembering this Irish Buddhist’s crossing of boundaries, and the worlds of multi-ethnic solidarity he represents, is an important resource for a better future.

About the authors:

Alicia Turner is Associate Professor at York University, Toronto; Laurence Cox is Associate Professor at Maynooth; Brian Bocking is Professor Emeritus at UCC. Between them they have published seventeen books on Buddhism, Burma, Japan and social movements.

The Irish Buddhist: the Forgotten Monk who Faced Down the British Empire is out now.