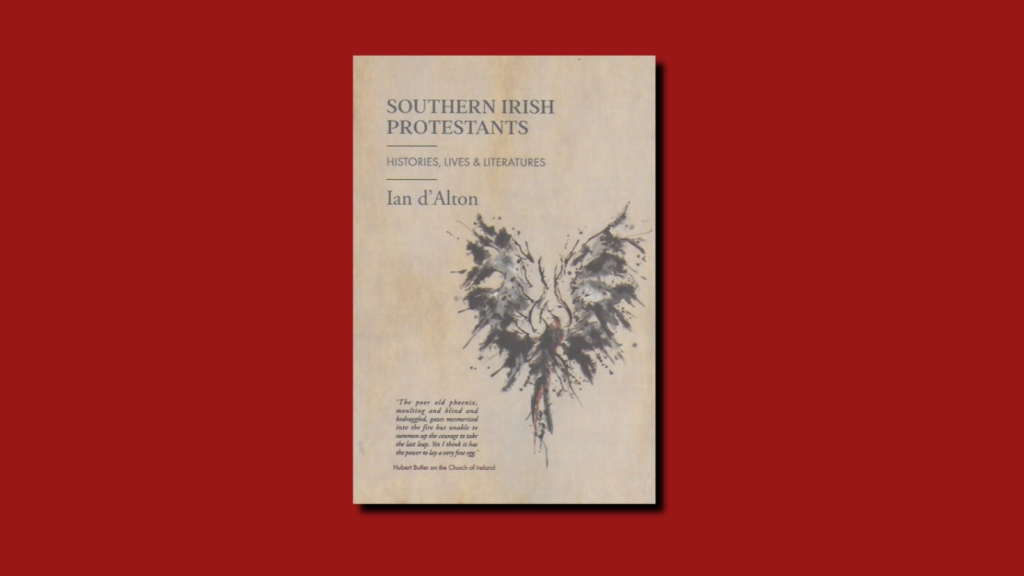

Southern Irish Protestants: Histories. Lives and Literatures, by Ian d’Alton (Eastwood Books)

Irish in England and English in Ireland—Southern Irish Protestants, by Ian D’Alton

by John Kirkaldy

Ian d’Alton’s Southern Irish Protestants: Histories, Lives and Literatures is an attempt to define and explain the status of Protestants within an independent Irish state. He sees a largely ‘confident minority’ and quotes approvingly a doggerel verse, written in 1907 by a Unionist in County Clare:

I am only a poor West Briton

And not of the Irish best;

But I love the land of Erin

As much as all the rest.

The book is divided into six sections: Protestant Culture and Protestant Lives; Explaining the Southern Irish Protestant; Literary Luminaries; Narratives of War and Rebellion; the Trauma of Partition and Regime Change; and Religious Disputations. The approach is historical and academic. There are 57 pages of doubled columns of footnotes and references. (I longed for an index.) Most of the book is concentrated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with only a few excursions up to about 1950. (D’Alton has addressed elsewhere the status of Protestants in a more modern Ireland. He is himself a Protestant.) Five out of the twenty-one chapters look directly at the experience of the Cork area; a major research interest of the author.

Protestants in the South is a story of decline in numbers and influence. The book explains: ‘The ascendancy of southern Irish Protestants subsides like a slow puncture from the end of the eighteenth century. One disaster followed another – the 1798 rebellion, the Union, the disestablishment of their church, the loss of land and ‘big houses’, the slaughter of the Great War, the 1916 Rising and finally Irish independence. They had to come to terms with living in an Irish Catholic state but from 1949 in a republic shorn of its links to the British monarchy.’ In 1922, Protestants numbered about 10% of the population; currently, it is about 4%. Yet, d’Alton sees a minority that has survived and prospered through ‘soft power.’

One of the most interesting chapters is a largely autobiographical one, which illustrates some of the complexities of exactly defining what a Southern Protestant really is. It is a central text of the book that they are different to Northern Protestants. He comments on class: ‘It existed all the way up, from a small working and agricultural labouring class, through farmers and urban professionals to the remnants of a vociferous and socially significant ‘Big House’ class. It even went further to the wider British landed class and then to the pinnacle, the Crown.’ He contrasts the differing experiences of being Protestant in Dublin and Cork, having lived in both.

The fault lines between the two denominations, as the South became more of a Catholic state were predictable

The fault lines between the two denominations, as the South became more of a Catholic state were predictable; examples were the Ne Temere decree on mixed marriages; the GAA ban on non-Gaelic sport; separate education; and the importance of the Irish language for public employment. Catholicism touched nearly every aspect of everyday life, such as politics, censorship, divorce, abortion and contraception.

What preserved the Protestant status was a policy of keeping their heads down. The writer and well-connected author, Patrick Campbell recalled: ‘I came from a Protestant home wherein Catholicism, and all its works, was the subject of constant derision.’ But these thoughts were not allowed outside the home. D’Alton also comments: ‘Money talked, as it always does, even if in muted tones. Protestants in the southern state comprised only 7 per cent of the population in 1926 but punched well above their demographic weight. ‘‘Protestant’’ generally meant ‘‘prosperous’’’. It should be noted, however, that there is also a long line of Protestant nationalist leaders, starting with Wolfe Tone down to Erskine Childers.

The articles are mostly the stuff of seminar or conference papers and the book will be a very useful addition to many university reading lists. (D’Alton is a Visiting Research Fellow at Trinity College, Dublin.) Much of the book is unlikely to interest a general reader, unless they had a particular interest in the specific topic under discussion. D’Alton writes clearly and is not prone to that academic tendency of using obscure concepts, words and phrases that make the reader all too often reach for the dictionary.

The book provides additional information and background to important milestones in Irish history—World War One, the Easter Rising, partition and the 1925 Boundary Commission. There are three chapters devoted to the Church of Ireland and religious disputes— disestablishment, independence and the Papal decree of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary in 1950.

It encouraged me to do what good literary criticism should always do: reach for the books discussed with fresh eyes and interest

The most effective section to me and I believe to the general reader are the chapters on ‘Literary Luminaries.’ It encouraged me to do what good literary criticism should always do: reach for the books discussed with fresh eyes and interest. D’Alton writes perceptively and with insight on Elizabeth Bowen, Molly Keane and Iris Murdoch. He recalls that female Anglo-Irish writers have a long tradition: ‘From Lady Morgan through Maria Edgeworth, Sommerville & Ross, Susanne Day and Dorothea Conyers to Barbara Fitzgerald and Jennifer Johnson.’

He provides fascinating biographical detail of Bowen and Keane and links their lives effectively to their writing. I relished Bowen’s upper-middle class Anglo-Irish hauteur rejoinder to aristocratic Lord David Cecil’s invitation to dinner: ‘David, I think you know by now that I want to see you either alone or at a large party.’ The demolition in 1959 of the ancestral home, Bowen’s Court, is seen as symbolic of the ending of the Anglo-Irish tradition of the Big House with its association of land ownership, hunting and dogs. D’Alton makes a convincing case of the hint of her Irish background in the writing of Iris Murdoch, especially in her only short story, Something Special. He writes that this link was more detached than Bowen and Keane: ‘Yet, though Murdoch may have seen her identity as Anglo-Irish; her writings might be characterised as Hiberno-English in style, tone and character.’

The book demonstrates that in this period the old truism about Protestants in the South remained correct: ‘Irish in England and English in Ireland.’

John Kirkaldy has a PhD in Irish History, worked for many years with the Open University and has been reviewing for Books Ireland since 1980. He has contributed to three Irish history anthologies, a school textbook, and has been involved in a number of Open University History documentary series. Aged 70, six years ago, he went round the world on a much delayed gap year described in his book, I’ve Got a Metal Knee: a 70-Year Old’s Gap Year. His latest book Life—A Fifty Fifty Path? is about luck and chance in history.