John McAuliffe

‘…books published this April feel like experiment subjects, subjects I hope will make it through the tests unharmed.’

In the past month, I’ve recorded a ‘virtual’ launch for Gallery on YouTube, filmed myself reading a poem in my garden for the Embassy in London, recorded an interview for the Poetry Programme from under a duvet (following the advice of producer Claire Cunningham) and set up a podcast called Unlaunched Books with two other poets, Seán Hewitt and Victoria Kennefick, to try to bring some of the news we expect to discover from (cancelled) festivals to interested readers. Is this new online context a supplement or a replacement for the festivals, bookshops and launches that were planned for the book? I don’t know yet, but books published this April feel like experiment subjects, subjects I hope will make it through the tests unharmed.

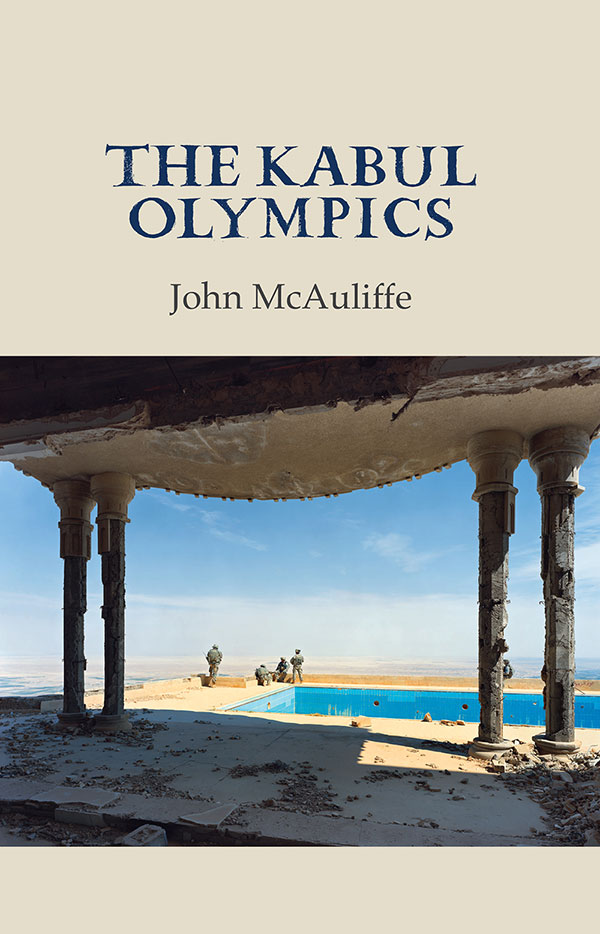

Until publication, my new book The Kabul Olympics had a typical enough trajectory—individual poems slowly emerging and then suddenly seeming to cohere, with certain images and themes drawing out other new poems in their wake. For this book, the pressure of global politics and the sense that individual lives and privilege are at the mercy of larger forces seemed to be driven home by the Manchester Arena bombing and the tumultuous Brexit debates. That bombing, for example, is the subject of a poem called ‘City of Trees’, which itself led me into poems about the Libyan community in Manchester (where I have lived since 2004) and then, in that sideways manner I have learnt to trust, a sequence called ‘The Harbours’, which remembers the gun-running activity, sometimes Libya-financed, off the Irish coast as I was growing up in north Kerry.

The relatively carefree day-to-day life and travel of my 21st-century emigrant life in the UK had begun, as I wrote the book, to seem more fragile. Unconsciously at first, my poems registered these new pressures. The book’s first poem, ‘Germany’, ends in the dark, on a European motorway, ‘going for the exit, full tilt / among the folk songs’; one of the ‘tuning fork’ moments that brings the book’s poems together is that sense of being on the edge of a different, and not necessarily better, world.

The title of the book comes from an elegy for my friend Caroline Chisholm. Caroline fell ill just as she was beginning to get her work ready for publication. Her novel was set partly in Swimming Pool Hill in Kabul, a city where she had worked, and her illness became apparent as she was preparing to swim the English Channel as part of her research into how Afghan migrants were attempting to escape the Jungle camps in Calais and make their way to the UK. After she died, though, it proved impossible to access Caroline’s last drafts of her novel, which were on password-protected files. So, in the title poem, I was thinking of that unfinished and now inaccessible book, and her hopes for it. These hopes lead us, as writers, to imagine seemingly impossible things. This is not to say that writers or poets are unacknowledged legislators, but the years of writing and thinking that make up a book are a kind of forfeit, a gamble, and I wanted in this poem to honour that idea and Caroline’s example. I chose the poem’s title for the book, because its combination of unlike things, of Kabul and Olympics—one a place associated with the oil wars of the last three decades, the other with a more benign sense of international relations—fitted the book and the way that the poems try to preserve individual experience as paramount while collective, social changes descended upon us.

‘Something unspoken can be something known. / Saying it would be another matter’ go that title poem’s last lines, which are about the difficulty of telling Caroline’s personal story, and also the parallel story of her unfinished novel, where the Olympic pool was drained and used as a place to train volunteers and for unspeakable acts of torture. Poems, and fiction, can dramatise how we know something, that act of discovering knowledge, and also, necessarily, our ignorance and doubt: that is, they don’t just tell us the facts. And that poem is also about my meetings with Caroline during her illness, as it advanced, something that did not need to be said, not to her. There is often in poems ‘something understood’, as George Herbert puts it. And I’m very interested in what it is that a poem can somehow communicate that is otherwise impossible to say—and in making a book that, in doing that, in trying to get into the darker corners of our particular moment in time, is useful for its readers.

***

John McAuliffe’s fifth book The Kabul Olympics (Gallery) is just out. He is one of the hosts of a new podcast, Unlaunched Books, and works as Professor of Poetry at the University of Manchester, the city where he has lived since 2004.