by Tony Canavan, Consulting Editor

It is well established that literary characters are often inspired by real people. It is said that the Victorian explorer, Richard Burton, was the physical model for Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and it is well documented that Ian Fleming based James Bond’s appearance on the singer and actor Hoagy Carmichael. In a different way, Arthur Conan Doyle was inspired to create his arch-villain Professor Moriarty by George Boole, first professor of mathematics at Queen’s College Cork. This was a case of what might be called reverse inspiration since Conan Doyle did not view Boole as an evil genius but wondered what would happen if his intelligence were possessed by an immoral character bent on wrongdoing.

In a similar way, Joseph Conrad was inspired by Roger Casement when he came to write Heart Of Darkness.

Regarded by many as Conrad’s best work, this novel has been adapted for stage and screen, and was the inspiration for Francis Ford Coppola‘s 1979 film Apocalypse Now.

Published in 1899, the novel concerns a voyage up the Congo River narrated by Charles Marlow. The novel explores ideas of civilisation and barbarism. The underlying notion is that there is little difference between “civilised people” and the so-called “savages”. Marlow is on a boat on the Thames when he narrates the story, and the book offers parallels between London (“the greatest town on earth”) and Africa as a place of darkness (proverbially, ‘the dark continent’).

Many see Heart of Darkness as a critique of imperialism and racism.

At the heart of the story is Kurtz, the ivory trader. Marlowe learns that Kurtz is in charge of an important trading-post and is widely respected. He is told that Kurtz is a “very remarkable person” who “sends in as much ivory as all the others put together”. It is said that Kurtz will go far. However when Marlow finally arrives at Kurtz’s station he finds quite a different situation. He sees a row of posts topped with severed heads, and it transpires that Kurtz has exercised a tyrannical rule over the Africans in his power, assuming the status of a demigod. The company manager who accompanies Marlow tells him that Kurtz has harmed the company’s business and that his methods are “unsound”. Kurtz believes the company wants to remove him, even kill him, but it doesn’t matter as he is dying anyway. In the end, it is clear that Kurtz despised the native Africans, recommending to the authorities: “Exterminate all the brutes!” His final words are “The horror! The horror!”

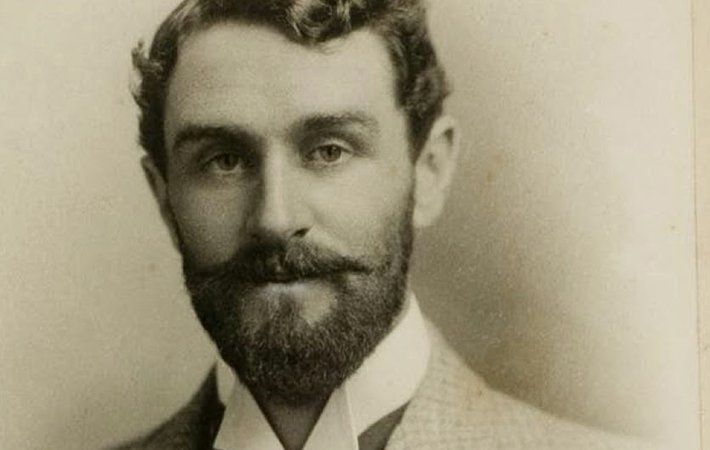

Joseph Conrad knew Roger Casement in Africa. Later Conrad recounted his first meeting with him. He was running his boat down the river when a tall, gaunt man arose out of the gloom.

At first Conrad thought Casement a sinister figure as he stood there with two servants crouching behind him as if in an act of worship.

It appears that this first impression never faded and even though the two spent months together in the same hut, for Conrad, Casement was always mysterious. However he did speak well of him, saying Casement “thinks, speaks, well, most intelligent and very sympathetic”. However after Casement’s trial, Conrad was more critical: “Already in Africa, I judged he was a man, properly speaking, of no mind at all. I don’t mean stupid. I mean that he was all emotion.”

Casement arrived in Africa in 1884 to work in the Congo for the African International Association. This was in fact a front for Belgium’s King Leopold II in his takeover of what became the Congo Free State. Casement recruited and supervised African labourers in building a railroad to bypass the lower 350 kilometres of the Congo River, which was unnavigable. In 1890 he met Joseph Conrad. Both were inspired by the idea that European colonisation would bring moral and social progress to Africa.

Casement transferred to the British Colonial Service being appointed British consul in 1891.

In 1903, the government asked him to investigate the human rights situation in the Congo Free State. Casement disclosed “the enslavement, mutilation, and torture of natives on the rubber plantations,” in his report of 1904.

When Casement wrote his report, he went to see Conrad, who was very uneasy about it. Conrad, by that time, sought to settle in England and wanted no trouble. Casement was appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George in 1905 for his Congo work, and in 1911 he received a knighthood for similar efforts in South America. He was subsequently involved with the 1916 Rising and executed at the hands of the British.

Like Conrad, Casement became disillusioned with European imperialism and went on to work for the benefit of native peoples. Conrad was impressed by Casement’s influence over the Africans who worked under him. He speculated what the outcome would be were another European to exercise similar control to very different ends—and so Mr. Kurtz was born.