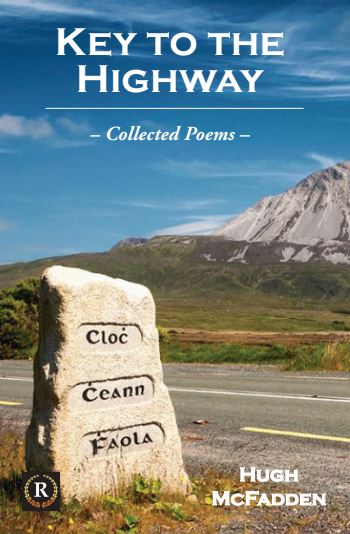

Key to the Highway:Collected Poems|Hugh McFadden|Revival Press

Key to the Highway—poems which trace McFadden’s life through the poets and events which shaped him

by Fred Johnston

First recorded by Blues pianist Charlie Seger (Big Bill Broonzy’s version is referenced here) and then by, well, just about everyone playing the Blues, the song that lends Hugh McFadden’s collection its title has become a Blues standard of the type that recalls heartbreak, the eternal need to ‘go,’ a relentless ordinary man’s battle with fate best waged with a pair of shoes.

I got the key to the highway

Billed out and bound to go

I’m gonna leave here running

Walking is most too slow . . .

The song is pure, raw poetry—it had to be for its audience and to stand any chance of being passed on by others. The Blues and all traditional folk song did not survive by standing still, but by a constant order of movement, re-ordering and even re-shaping. It was of the nature of oral poetry: it was ‘spoken word’ before the term became a fashion.

There is a lot of movement in McFadden’s poetry in time, place, relationship, observation. There’s something too of the twelve-bar rhythm, the ordered insistence of line and progression, the resolution. And the murmuring consistency of music. Which is not to state that all the poems here are echoes of the Blues by any means.

There is a lot of movement in McFadden’s poetry in time, place, relationship, observation

A Derry man by birth, McFadden’s literary itinerary was shaped around Dublin, a gradual Dublinisation forged around the writers of his era: Patrick Kavanagh, the scholarly John Jordan, the rambling Michael Hartnett, the fledgling Paul Durcan. It was a lively Dublin, untrammelled by the madcap rush for celebrity that arrived with the industrialisation of poetry through gusts of workshops and weekend primers.

It created ‘characters’ as well as poets, often both inhabiting the same flesh and the same pubs and seems to have had its muttering rivalries without the subsequent cold malice. Poets were still viewed from the side of the cautious eye and their true worth was not always appreciated, let alone celebrated. But it must have possessed a particular enchantment, because few writers who waded through the period forgot it or remained uninfluenced by it.

It was eventually to be crucified by respectability, a lust for glittering prizes and a hack’s notion that poetry was so useless that ‘everyone’ could be a poet. But that was later. In 1973, roughly – we’re told – where this collection lifts off, poets were still poor but honest. By and large.

A Derry man by birth, McFadden’s literary itinerary was shaped around Dublin, a gradual Dublinisation forged around the writers of his era

Inevitably, civil change was afoot, as was sleeveenism. Dedicated to Pearse Hutchinson, McFadden’s ‘Demolition Dublin (1969) announces it; in novel form, English writer Brian Cleeve’s ‘Cry of Morning’ (1971) was to add the spice of corruption. Says McFadden:

Guard dogs beware . . .

do not trust the hand that feeds you,

for the men of great property

would starve you for a slim profit . . .

Easy enough to notice, whether unconsciously planted or otherwise, the distinctly Gaelic/satirical poetic phrasing and rhythm and word-use here, reminiscent of a 17th or 18th century poem on imminent decline and fall. It could be a translation (it’s not). It could easily have stumbled out of Thomas Kinsella’s ‘An Duanaire.’ As it stands in terms of poetry and meaning it strikes a quiet genius note. Dublin was about to lose her soul; little wonder that poetry started to barter hers.

McFadden is a subtle observer—he went through the beloved Irish Press, as John Banville did, as I did too, later. Maybe a touch of sub-editing provoked the need for precision in observation? The Irish Press seemed to breed creative writers. Hardly surprising, then, that McFadden pays homage to the late David Marcus, Literary Editor there from his office overlooking the river Liffey and without whom, arguably, many of the writers around and writing today might never have seen print.

Marcus was a thorough literary gentleman of the Old School, had known the prominent figures around The Bell, and his Saturday ‘New Irish Writing’ page was the gold standard for embryonic prose writers and poets. Over a cup of tea at his paper-strewn desk he would with great patience scrutinise one’s manuscript and explain every tick and suggested alteration, in effect providing a condensed masterclass. He kick-started a ‘modern’ renaissance in Irish literature through those pages which eventually included home-grown publishing.

‘Then, after eighty-four years, you were gone,’ McFadden laments in ‘David’s Farewell,’ a poem which is a description of Marcus’ funeral and a lament for the passing of a much-loved literary statesman. The very title of the poem echoes Gaelic laments for the passing of chieftains.

As the poet grows older – some would say ‘matures’ – the work lifts its head into reflective humour and satire, peppered with poems of intensely moving and personal lyricism

Sean Lemass had worked to change the ‘Island of Ireland,’ wherever that is. Viet Nam had been an issue for the cheese-clothed young – the pulling down of Dublin had seemed to coincide. And the Northern Ireland ‘Troubles,’ happening in a country which, for many, remained at least as distant as South-East Asia, intruded with the Dublin and Monaghan bombings of 1974 and the music itself was murdered with the massacre of the Miami Showband in the following year. McFadden recalls that:

Too soon the music was gone,

now the chant was ‘revolution’:

rubber bullets, stones, barricades . . .

(from ‘Morning Dream’)

Music of the sixties and seventies can still provoke entire Facebook entries of nostalgia. Yes, the music was better back then and more memorable, as witness teenage street-musicians today belting out early Dylan numbers. In ‘Coming Together Right Now,’ (if you know, you know) McFadden right-ons Blind Faith/Steve Winwood, Abbey Road, and Dylan’s ‘All Along the Watchtower.’ The music was a multi-faithed guru, a moral and political tracking device, whether one was playing it or listening to it.

Sometimes I want to get out of it now

but the GPS doesn’t know the time . . .

As the poet grows older – some would say ‘matures’ – the work lifts its head into reflective humour and satire, peppered with poems of intensely moving and personal lyricism. As the younger cadre of poets chased the new prizes and a sort of fame, some younger politicians at least seem to have aimed themselves at Europe and the goodies available there. Ireland became a player. Who can forget, however, the roar of the Celtic Tiger fading into a whimper?

An astute German Envoy, Herr Pauls

cried ‘This Celtic Tiger appals:

the feline lacks class

its manners are crass

and its fame is a load of old balls.

(From ‘A Berlin, not Boston, Limerick’)

McFadden’s poetry ranges widely and there is a genuine concern for how we dealt with politics. There is a great concern too for poets, especially, one feels, Hartnett, a poet trapped between the Gaelic and the English world and who, for this reviewer’s money, tried to bridge the gap, not always successfully. When McFadden writes touchingly about family, he writes with a not indifferent warmth for the poets he has admired or known. Are they ‘family’ too? The affection with which he writes of Seamus Heaney in a ‘dream’ poem is evident

without at all being cloyingly reverential.

It was a most peculiar dream,

Seamus, and you entered into it

when you appeared in my sitting-room

where I was examining some books . . .

(From ‘Encountering the Poet’)

Indeed McFadden’s work never allows us to forget that poetry is a form of meeting, of continual meeting and conversing, and that in whatever form it holds out its hand, it’s an invitation to a dialogue. There are five collections represented here, running up, more or less into the mid-Noughties. They afford us an opportunity not merely to chart a poet’s progress, but to visualise it against the run of his times, which are our times, too. For some of us, his griefs, his exultations and his arguments mirror ours as surely as they mirror those magnificent decades of our growing.

Indeed McFadden’s work never allows us to forget that poetry is a form of meeting

He says in one poem that we moved from an age of anxiety to an age of terror. The terror for us was close to home – as writers, was it as relevant as Viet Nam? Where stood the lyric poem in all of that? How might cynicism be avoided? We have access to worlds unimaginable from the 1960s bar counters of Dublin. So can poetry compete with the fantasies of TikTok? The terror hasn’t lessened, it’s become even more ubiquitous. And we are permitted to discuss it less and less; perhaps a certain lyric note has faded out of our poetry too. There are things we must adhere to, hold on to. Poetry may be the key to the highway.