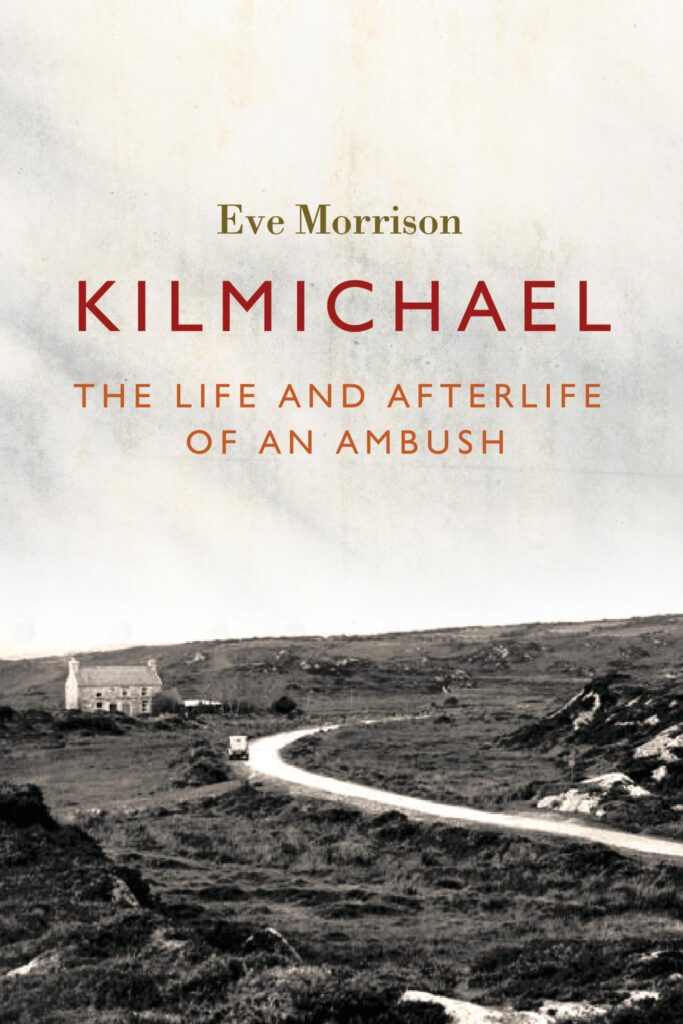

Kilmichael: The Life and After life of an Ambush| Eve Morrison|Irish Academic Press|ISBN: 9781788551458|€19.95

‘Nobody interested in this controversy in the future can ignore Morrison’s work.’

—John Kirkaldy reads an impressively researched and important book on the Kilmichael ambush.

by John Kirkaldy

Between 4.05 and 4.20pm on 28th November 1920, an ambush of a convoy occurred near the village of Kilmichael in County Cork.

Thirty-six local IRA members of the West Cork Brigade, led by Tom Barry, killed sixteen members of the Royal Irish Constabulary’s Auxiliary Division. The IRA lost three men killed in the skirmish.

A week before the attack, Auxiliaries had fired on players and spectators in a Gaelic football match at Croke Park, Dublin, killing fourteen civilians (thirteen spectators and one player), in what became known as Bloody Sunday.

The Auxiliaries in the Cork area were based in the town of Macroom and during November 1920 had carried out a number of raids on villages, as part of reprisals and counter reprisals in a spiralling level of violence.

As Eve Morrison observes in her introduction, at the end of the War of Independence: ‘the Kilmichael ambush still represented the greatest loss of life inflicted by the IRA on Crown Forces in a single instance during the conflict’.

Controversy

As soon as the last shots were fired, the controversy started and has not stopped since. Initial reaction was predictable—very much along the lines of my ‘freedom fighters’ as opposed to your ‘terrorists’.

An early telegram from Sir Henry Tudor, Police Adviser to the Irish Administration, quoted by Morrison, claimed exaggeratedly: ‘the Auxiliaries were then disarmed and brutally exterminated. The ‘dead and wounded were hacked about the head with axes’ and ‘gun shots were fired into their bodies’. The IRA then robbed the ‘savagely mutilated’ bodies and drove away.’

Tudor wrongly claimed that ‘eighty to 100’ IRA members had been involved.

Morrison comments: ‘The response of Sinn Féin publicists was to focus on the Crown Forces’ retaliatory reprisals, dismiss the mutilation accusation as war propaganda and explain (rather than deny) the conditions of the bodies. The injuries were attributed to ‘bomb fire.’’

Public opinion

It is good to be reminded that public opinion in Britain and Ireland was not always clear cut. British newspapers, such as the Manchester Guardian and the Glasgow Evening News, were critical of the Government’s policy of reprisals.

Arthur Henderson, the Labour leader, commented: ‘these reprisals appear to us to be a deliberate and calculated effort to destroy the Irish political movement.’

In November 1920, Labour formally adopted a manifesto recognising Ireland’s right of self-determination, calling for a withdrawal of the ‘British Army of Occupation’.

The Manchester Regiment’s war diary of the time found that ‘the civilian population were nervous, rarely welcoming and often hostile. Shop keepers were reluctant to serve them. Railway men refused to load military stores.’

The tide was definitely turning but not everybody supported the IRA’s tactics.

Inaccuracies and inconsistencies

It would be almost impossible to produce a totally accurate account of nineteen deaths, largely killed in frantic hand to hand fighting with guns and bayonets, which took place over a few minutes.

It would hardly be surprising if there were not some minor inconsistencies and inaccuracies, especially over time.

The standard nationalist account is that of Barry in his influential memoir, Guerrilla Days in Ireland; another important first-hand account is by Stephen O’Neill. (Divisions within the West Cork IRA were highlighted by the publication in 1973 of Liam Deasey’s book, Towards Ireland Free, which was very critical of Barry.)

Crucial issues

Far more important are three crucial issues: did the IRA disguise themselves in Crown uniform in order to stop the convoy; during the fighting were surrender and false surrender pleas proclaimed and ignored (claims have been made that unarmed men were shot); and were Auxiliary bodies mutilated and abused after death?

The amount of existing passions that still exist, despite these events happening over a century ago, is illustrated by the fact Morrison was denied access to a few archives and several interested parties refused to speak to her.

Further controversy

More controversy was developed even further by the publication in 1998 of Canadian academic, Professor Peter Hart in his book, The IRA and Its Enemies: Violence and Community in Cork 1916-1923.

Hart was very critical of Barry’s version of events and further claimed that the killing of thirteen Protestants in the Bandon Valley in April 1922 was the result of sectarianism. He also largely saw reprisals and counter reprisals as being part of a whole, rather than simply right versus wrong. (Morrison is supportive but not uncritical of Hart’s general arguments, claiming, for example, that Barry produced five different accounts of the ambush over time.)

Impressive research

Morrison’s research is by any standard very impressive. There are five appendices, giving differing accounts and views of the ambush, 59 pages of detailed footnotes and a very comprehensive Bibliography. The book is helped by a clear and well organised style.

Nobody interested in this controversy in the future can ignore Morrison’s work.

Another important part of her book is the attempt to set the ambush in the context of Irish politics and culture. The fight for independence was long, hard and complex.

Perceptions of the ambush were filtered by subsequent events: the divisions of the Civil War; the creation of the two political parties based on that conflict; and the whole question of partition.

Every country has to fit its past into its perceived national identity, even though some aspects may not quite fit.

Recent crisis

The recent crisis in Northern Ireland exacerbated these feelings even further. Revisionist historians, led by Roy Foster and Ruth Dudley Evans, urged a fresh appraisal of Ireland’s past; while traditionalists, such as Brendan Bradshaw, urged for continuity. (This made for some lively Books Ireland Christmas parties in the 1980s and 90s.)

Morrison ends in fine style. ‘Is there a Kilmichael around which all can rally and remember? At present it does not seem so. What stands out for this historian are those few moments when two men, surrounded by death, looked each other in the eye and decided not to fire:

‘He could have shot me and I could have shot him but I thought it was the bravest thing I could do, maybe, at the time.’

John Kirkaldy has a PhD in Irish History, worked for many years with the Open University and has been reviewing for Books Ireland since 1980. He has contributed to three Irish history anthologies, a school textbook, and has been involved in a number of Open University History documentary series. Aged 70, four years ago, he went round the world on a much delayed gap year described in his book, I’ve Got a Metal Knee: a 70-Year Old’s Gap Year.