Ballymacandy: The Story of a Kerry Ambush|Owen O’Shea|Merrion Press|paperback €14.95| ISBN: 9781785373879

This is local history at its best: clearly written and cliché free, painstakingly researched

by John Kirkaldy

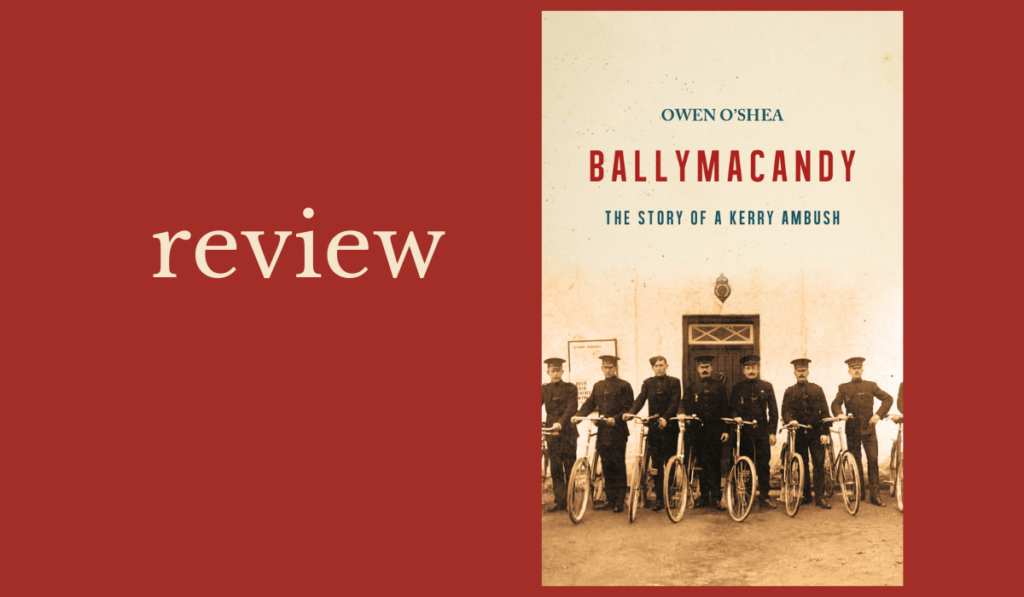

On 1st. June 1921, at the height of Ireland’s War of Independence, a cycling unit of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and Black and Tans was ambushed by the IRA at Ballymacandy, between Milltown and Castlemaine in County Kerry. Through meticulous scholarship and research, Owen O’Shea not only provides a first-class account of the hour-long battle but also the complex forces surrounding it.

At the end of the ambush, four of the group lay dead and another died a day later. Five Irishmen killed by other Irishmen; one a father of nine, who lived in the same village as many of the men who attacked him.

There is no doubting where O’Shea’s nationalist sympathies lie (he is also a local boy) but his riveting description is not just a simplistic ‘goodies’ versus ‘badies’ history; it is also an analysis of rural Ireland at a time of acute political turmoil. The IRA was condemned from the pulpit and an official enquiry tried to discredit the local doctor, who was accused of neglecting a dying man. A local priest, in contrast, prayed into the ears of the dying. The attack was helped by an IRA sympathiser within the police.

From 1918 onwards, crown forces were rapidly losing control of Kerry and many other parts of Ireland. In 1919, fifteen RIC men were killed; a year later the figure had risen to 179.

It was the arrival of the Black and Tans and the Auxiliaries that ratcheted up this spiral of violence even further. (O’Shea is right to remind us that many of these were local; one in ten of the Auxiliaries were Irish born.)

The RIC

The RIC, although associated historically with eviction, was not universally unpopular prior to 1918. In 1920, there were almost 10,000 members in 1300 detachments across the country. It was seen as a safe career with good pay, uniform, accommodation and a pension.

They lived where they policed; sometimes in the community, rather than police barracks, often married local girls, and their families attended communal churches and schools. O’Shea highlights the parallel lives of two leading figures on opposite sides in the ambush – RIC Sergeant James Collery and IRA leader, Dan Mulvihill. Some members of the RIC resigned from the force, partly through intimidation but also in some cases with a degree of support for rising nationalism.

Guerilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is not only about body counts but also hearts and minds (what Mao likened to the fish that swim in the sea). In the period, 1918-21, the IRA was definitely winning this battle. Attacks and reprisals edged public opinion towards militant republicanism, especially among the young. The IRA built up a very effective local network; it even had something of a semi permeant base at the Hut, a hideout on the Dingle peninsular. O’Shea shows how important the women’s group, the Cumann na mBan, was in this process.

O’Shea is adept at analysing the various strands of local Irish society.

When the IRA commandeered the Anglo-Irish gentry, Major Leeson Marshall’s car, the owner was told, ‘sorry to upset you, Major, but we must obey orders.’ Protestants were disturbed by slogans daubed outside the local Church of Ireland, such as ‘England Out’. The British coat of arms was hacked off the front of the Crown Hotel and the rubble strewn on the ground. There were reminders of constitutional approaches to Irish affairs by Tom O’Donnell, the MP for West Kerry, who in 1914 told a local audience that Home Rule would mean the removal of ‘the yoke of landlordism’.

The ambush

Two chapters only are devoted to the actual details of the ambush. On the morning of the attack, a group of twelve (three RIC and nine Black and Tans) set off from Killorglin, under the leadership of District Inspector, Michael Frances McCaughey. Seven of the group were Irish born. They were to cycle to Tralee to collect their pay. On the return journey, they were ambushed at Ballymacandy. The IRA was tipped off about their journey, especially as they stopped off at a pub on the way home. An attack was predictable but McCaughey, in the words of an opponent, ‘would not turn off the road for any “Shiner”.’

It was not an obvious place for an attack; at the time, it was a straight road with little cover. There were several other places, which might have made a better choice. Its attraction was, in the words of Mulvihill, a good position because there was ‘no position’. According to the leader, Tom O’Connor, half the assailants had rifles and half, shot guns.

The patrol left Griffith’s Bar in Castlemaine at 3.30 pm, travelling in six pairs of two; half a mile down the road, the IRA waited.

O’Connor explained that dozens of men were ‘strung out for four fields’, along a few hundred yards. He waited to give the order to ‘open fire’, until the patrol was very close, as the range of the shot guns was limited.

Compelling picture

O’Shea uses a wide variety of resources to produce a compelling picture: census forms, newspapers, court of enquiry testimony, post mortem details, written reminiscences and pension claims. Of particular interest are the memories of two young boys, Denis Sugrue and Thomas ‘Totty’ O’Sullivan. There is much graphic detail. An eye witness described the dead body of McCaughey, ‘blood was slowly trickling from his left ear and the jaw was twisted.’ The IRA suffered only one wounded.

This is local history at its best: clearly written and cliché free, painstakingly researched, a useful index, a really clear map, interesting photos and placing the ambush in the context of Irish history at the time and its aftermath.

The book ends on a sombre note. Only a few months later, members of the attack and the IRA generally were fighting each other over the Treaty of December 1921; more Irishmen killing each other. The resulting fault lines may be receding in Irish society but they are still there.

John Kirkaldy has a PhD in Irish History, worked for many years with the Open University and has been reviewing for Books Ireland since 1980. He has contributed to three Irish history anthologies, a school textbook, and has been involved in a number of Open University History documentary series. Aged 70, two years ago, he went round the world on a much delayed gap year described in his book, I’ve Got a Metal Knee: a 70-Year Old’s Gap Year.