Anglo-Irish elegy—Elizabeth Bowen and the loss of a class

It may seem a strange way to start but, first off, we have to ask: was Elizabeth Bowen Irish? Reference works usually describe her as Anglo-Irish or even British-Irish. While she did come from a family who had been in Ireland for centuries, she spent most of her life in England and her readership was to be found there. For some, her activities during World War II showed where her true allegiance lay. She visited Ireland to write confidential reports for Churchill’s government on the mood of the country, attitudes to De Valera’s opting for neutrality and so on. Some view this as acting as a spy, although she was hardly Mata Hari. One critic commented that her imaginative settings are set firmly within the world of the English upper middle-class and the Anglo-Irish ascendancy. It is clear that Bowen identified herself as Anglo-Irish and much of her writing is focused on life in the ‘Big House’, lamenting the decline of that class. Whatever passport she may have carried, however, Bowen was born and bred in Ireland, and we are entitled to claim her as ‘one of our own’.

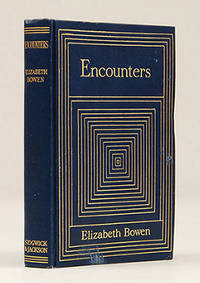

London: Sidgwick & Jackson,1923

Regarded by many critics as one of the most important novelists of the twentieth century, Elizabeth Dorothea Cole Bowen (1899–1973) was born in 15 Herbert Place, Dublin, and baptised in the nearby St Stephen’s Church on Upper Mount Street. Her parents, Henry and Florence, brought her to live in the ancestral home, Bowen’s Court at Farahy, Co. Cork. When her father became mentally ill in 1907, she and her mother moved to England, eventually settling in Hythe. Upon her mother’s death in 1912, Bowen was brought up by her aunts. After trying art, she decided that her talent lay in writing and she published her first book in 1923, a collection of short stories entitled Encounters.

In that year she married Alan Cameron, who went on to work for the BBC. The marriage has been described as ‘a sexless but contented union’. Bowen had various extra-marital relationships, including an affair with the Irish writer Seán Ó Faoláin and an involvement with the American poet May Sarton. Bowen and her husband lived near Oxford, where they socialised with Maurice Bowra, the classical scholar and literary critic, and author John Buchan and his wife Susan. Here she wrote her early novels, including The Last September (1929). Following the publication of To the North (1932) they moved to London. In 1937 she became a member of the short-lived Irish Academy of Letters.

She became the first (and only) woman to inherit Bowen’s Court in 1930, although she remained based in England. She continued to visit Ireland, and during World War II, working for the British Ministry of Information, she reported on Irish society. She wrote what are regarded as among the greatest interpretations of life in wartime London—The Demon Lover and Other Stories (1945) and The Heat of the Day, published in 1948, the same year she was awarded a CBE. She was also a writer of ghost stories, praised by one critic as ‘the most distinguished living practitioner’.

She and her husband settled in Bowen’s Court in 1952, but he died a few months later. Many writers visited her there, including Virginia Woolf (who described Bowen as ‘very honourable horse-faced, upper class’), Carson McCullers and Iris Murdoch. For years Bowen struggled to keep the house going, lecturing in the United States to earn money. It is said that the strain finally got to her and she had a nervous breakdown. She abandoned Bowen’s Court to live in England, leaving unpaid wages and bills. In 1960 she sold the house, which was demolished.

Her final novel, Eva Trout, or Changing Scenes (1968), won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 1969 and was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 1970. Subsequently, she was on the panel (alongside her friend Cyril Connolly) that awarded the 1972 Man Booker Prize to John Berger’s G. Bowen developed lung cancer and died in University College Hospital on 22 February 1973, aged 73. She is buried with her husband in Farahy churchyard, close to the gates of Bowen’s Court, where a commemoration of her is held annually.

Although Bowen’s novels have rarely been out of print, she is hardly a household name in Ireland today. People may be familiar The Last September because it was turned into a film in 1999 with a screenplay by John Banville. It is an elegiac evocation of Big House life in Ireland. In The Last September, Bowen drew on her childhood summers at Bowen’s Court and other autobiographical elements, such as her short-lived engagement to a British army officer in 1921 during the War of Independence. The main theme of the novel is the passing of the way of life of the Anglo-Irish gentry. Some Irish readers are drawn to this Irish version of antebellum romanticism of a lost cause, while others see this as a reason to disapprove of Elizabeth Bowen.

***

Tony Canavan