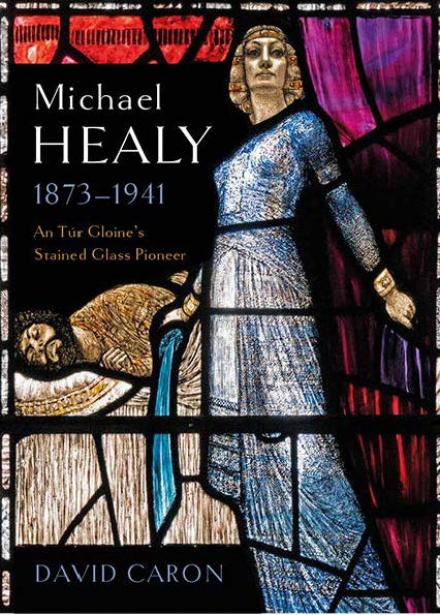

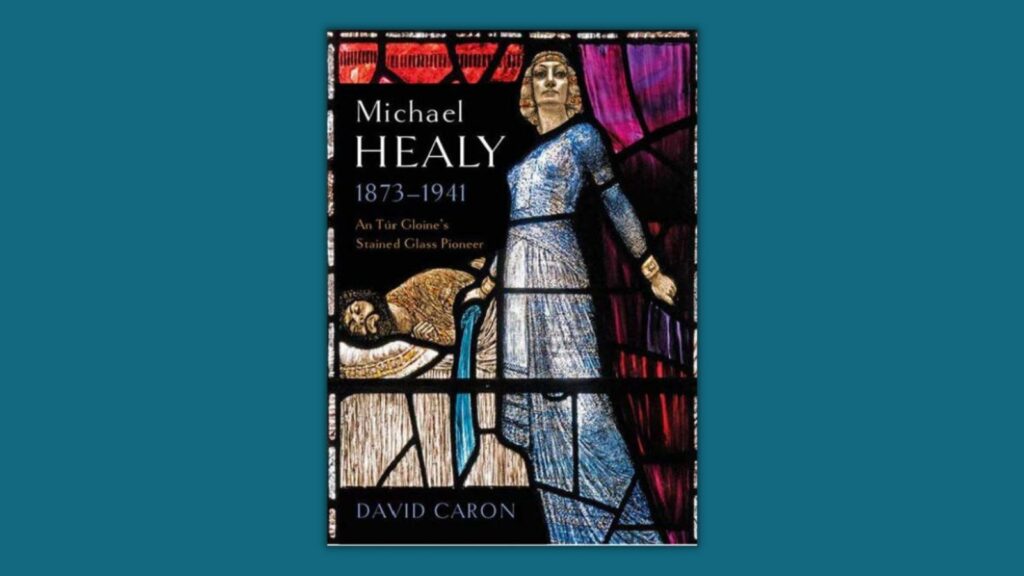

Michael Healy 1873-1941: An Túr Gloine’s Stained-Glass Pioneer|David Caron|Four Courts Press

Isolde Goggin explores a volume which is much more than a history of stained glass

by Isolde Goggin

Irish stained glass has been well served by publications in the last decade or so, notably Nicola Gordon Bowe’s biographies of Harry Clarke and Wilhelmina Geddes, Lucy Costigan and Michael Cullen’s detailed works on Clarke and, in 2021, Gordon Bowe, David Caron and Michael Wynne’s magisterial Gazetteer of Irish Stained Glass. Caron’s latest work, beautifully illustrated with photographs by Jozef Vrtiel, is a wonderful addition to the literature.

It follows Healy’s career chronologically, detailing all his works (including much fascinating information on the techniques used), and includes a glossary, comprehensive notes and bibliography. However, it is much more than a book about stained glass: it provides deep insights into the social history of the time, showing both the appalling poverty of much of late nineteenth-century Dublin and, at the same time, the hope that could be glimpsed through adult education, philanthropy and, occasionally, pure luck.

it is much more than a book about stained glass: it provides deep insights into the social history of the time

If Harry Clarke, the son of Joshua Clarke of Joshua Clarke & Sons Stained Glass Studios in Dublin, was born to be a stained glass artist, Michael Healy’s career was far more unlikely. He was born in 1873 into extreme poverty in Dublin, the eldest of six children of a labourer who died in the workhouse at 50; one sister died as a child, and a younger brother in his thirties, after burying three of his four children.

The family moved frequently between various one-room tenement lodgings, but stuck closely to the Bride Street/Bishop Street area, around St Patrick’s Cathedral. Healy, a solitary child who loved drawing, left school at 14; when he enrolled in art classes at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art in 1892, his occupation was described as “sugar-boiler”.

Pioneering

How, then, did he become a pioneering stained-glass artist? Caron describes “three transformative strokes of good fortune in his life”. Firstly, Fr. H.S. Glendon, the editor of The Irish Rosary magazine, to which he had submitted illustrations, spotted his talent and arranged for him to spend eighteen months in Florence studying art, ensuring he had enough illustration and copying work to live on; this exposed Healy to Renaissance art, an influence which permeated his work throughout his lifetime.

Secondly, the sculptor John Hughes recommended him to Sarah Purser, who was then establishing An Túr Gloine, based on his drawing skills; he began attending A.E. Child’s stained glass classes at the DMSA in 1902 and worked at An Túr Gloine from its inception in January 1903. Finally, in terms of his personal life, he formed a long-term, stable relationship with his landlady, Elizabeth Kelly, which lasted until his death in 1941.

Healy’s work can be seen in Penang, Malaysia; Wellington, New Zealand; Newfoundland, Canada; and various locations in the United States

A refreshing aspect of the revised Gazetteer of Irish Stained Glass was its international aspect, with works of Irish artists being found as far afield as South Africa and Singapore. Likewise, Healy’s work can be seen in Penang, Malaysia; Wellington, New Zealand; Newfoundland, Canada; and various locations in the United States.

Windows commissioned in 1913 for St. Peter’s Church of England church in Wallsend, Tyne and Wear, illustrate the interconnectedness of Irish artistic circles at the time: the rector was the Reverend Charles Osborne, brother of the painter Walter Osborne and a graduate of Trinity College, Dublin. The brothers were relatives of Sarah Purser, who seems to have been an energetic and effective networker; two further commissions for the same church were received later.

Another connection was with the Lewis family of Belfast

Another connection was with the Lewis family of Belfast. In 1931, Captain Warren H. Lewis and his brother Jack commissioned a three-light window (St. Luke, St. James and St. Mark) in memory of their parents for St. Mark’s Church of Ireland church in Dundela, Co. Antrim; Jack was later better known as the writer and theologian C.S. Lewis.

Democratic

Our self-image as a nation does not include a great appreciation of the visual arts; we think of ourselves as a nation of writers, and are happy to exploit that legacy for commercial purposes. Visual art is locked away in city galleries, the subject of pilgrimages. Yet, because much stained glass was commissioned for ecclesiastical buildings, it is surely more democratic: it was designed to be seen by large groups of people engaged in their weekly routine.

because much stained glass was commissioned for ecclesiastical buildings, it is surely more democratic

One could be sitting in a small, draughty, rural parish church and yet be in the presence of a stunning masterpiece of twentieth-century art. Healy himself would have been familiar with stained glass from his local church in Whitefriar Street, where he was an altar-boy. One example which is highlighted in the book is that of the tiny Catholic church of Bridge a Crinn, Co. Louth. The Healy window, commissioned by the parish priest, Fr. Lawless, in 1923, commemorates local farmers Thomas and Judith Treanor; the main panels feature Christ appearing to Doubting Thomas, and a dazzling Judith (featured on the front cover) about to decapitate Holofernes.

There could be no better Christmas present for the art-lover in your life

Smaller vignettes depict the Agony in the Garden, a farmer ploughing a field with oxen, a blacksmith, a potter and, pleasingly, local figures Sodelb of Cen and St Sillan of Cassian Cuailgne. As with many such churches, no information about the window (or about another opposite, also from An Túr Gloine, by A.E. Child) is provided on site. Perhaps the authorities do not wish churchgoers to be distracted by secular considerations, but it seems a pity that what should be a focus of local pride remains unknown to many.

This is just one of many thought-provoking examples in this wonderful book. There could be no better Christmas present for the art-lover in your life.